Photo courtesy of The India Forum

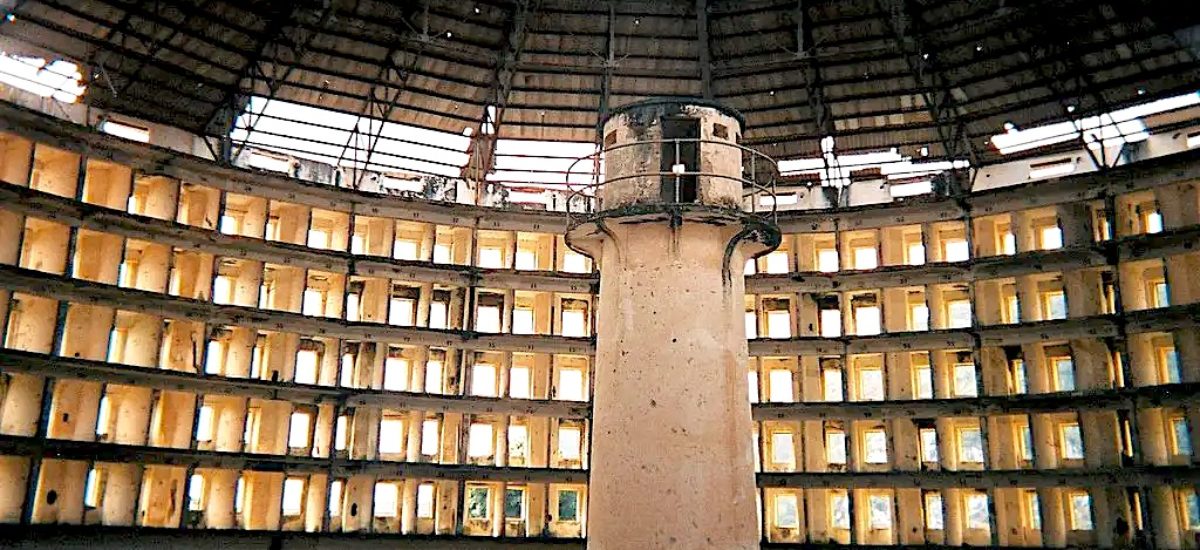

“Hence the major effect of the Panopticon: to induce in the inmate a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power.” Michel Foucault

Although now contested, news of the first arrest under the Online Safety Act (OSA) renders more urgent, and underscores points made last week at a public lecture organised by the Bandaranaike Academy for Leadership and Public Policy (BALPP) on a panel chaired by Prof Arjuna Parakrama, and also featured Prof Savithri Goonesekara. Following up my September 2023 article on Groundviews, this article captures key aspects of my BALPP lecture and also reflects key points in a note penned on the eve of the parliament debate which informed, at their request, some of the floor presentations of MPs who opposed the passage of this Act.

My critique of the OSA is anchored to subject/domain expertise at the intersection of studying policies dealing with online harms, context-specific input to leading social media companies to help them understand better content inciting violence, the study of Sri Lanka’s surveillance architectures, and primary research on foreign malign influence operations (FMIO) on social media. Being at the confluence of these four areas for over a decade provides key insights into the strategic design, and now, operationalisation of the OSA.

Minutes after the BALPP session ended, Irene Khan, the UN Special Rapporteur Freedom of Opinion & Expression tweeted “I am disappointed the Online Safety Act was adopted despite serious concerns that it would endanger Freedom of Expression in Sri Lanka”, pointing to very serious concerns around the Bill published in November 2023, which almost entirely hold in the final version of the legislation hurriedly rushed through parliament. We now know why it was all so rushed. The first arrest under the OSA wasn’t to protect children, or women. It was against what’s self-servingly, and vaguely presented as a “smear campaign” and “slander” with “the support of a politician”. The Public Security Minister also noted “These campaigns can even be used to change governments”. This is an illuminating statement. Writing in December 2023, Uditha Devapriya highlighted a “deeply polarised political climate, and with an even more polarising election season on the way” for 2024. This succinct capture has significant online, and social media dimensions which after 2022’s aragalaya, those in power, and want to hold on to it, dread. This vaulting fear, and the resulting imperative to contain, censor, and control inconvenient narratives, is what undergirds the OSA.

Noting at the outset that any reform of the OSA is impossible, that it was irredeemably flawed, and that it must be wholly rejected, I also dismissed proposed amendments as those intended to stop industry from exiting Sri Lanka as a market altogether, because of compliance structures that are impossible to service, and not intended to safeguard citizens. I raised several major issues with the Act. These include risks of conflicting government authorities overseeing local and international content; negative impacts on digital businesses from increased regulations; privacy threats caused by expanded state surveillance; extremely vague definitions of “harmful” material; freedom of expression limits that have global impacts; lack of independent oversight on content take-down orders; and economic harm to creators and media facing severe penalties limiting their work, and revenues. Others in Sri Lanka have discussed these problems much more extensively. But the core worries stem from the Act granting authorities broad, arbitrary powers with unclear boundaries and little accountability, enabling crackdowns on dissent, public debate, and digital innovation.

Mindful of what so many others have already said opposing the OSA, I focussed my presentation around four points. The first was the possibility of partisan misuse, and abuse, with politically motivated arrest of Tamil journalist J.S. Tissainayagam nearly two decades ago as a harbinger of what at scale will be realised through the OSA. Second was the concern that government authorities will weaponise their power of partisan, expedient interpretation around what constitutes “harmful content,” using the deliberately vague terminology in the ACT to target dissenting voices. The third was the risk that the Act will enable far greater invasive, and pervasive surveillance over citizens, and imbricate content regulation with spying powers. Finally, and connected to the first point, I warned the OSA will open the floodgates for political misuse, and abuse, where partisan motivations lead to the suppression of dissent. The first case under the OSA has, in a matter of days, already realised this fear. It will get worse.

The OSA makes it illegal for anyone inside or outside of Sri Lanka to spread false information online that could threaten national security, public health, or public order. It also prohibits posting content promoting ill-will or hostility between different groups of people in the country. Those found violating the law may face up to 5 years in prison, fines up to 500,000 rupees, or both penalties.

J.S. Tissainayagam was detained by the much feared Terrorism Investigation Division (TID) in 2008. Evidence presented by the government included a July 2006 editorial penned by him accusing the security forces of failing to protect, and killing Tamils, and a November 2006 article by him describing military offensives deliberately starving and depopulating Tamil civilians in Vaharai. In 2009, Tissainayagam was sentenced to 20 years hard labour for this writing, which the Sri Lankan government claimed incited ethnic tensions. Mirroring charges of “arousing communal feelings” brought against Tissainayagam, the OSA bans online speech threatening “public order”. The vague framing of offences in the OSA – deliberate, and by design – gives authorities wide discretion to suppress dissenting voices, and critics including investigative journalists. As such, I said the OSA enables arbitrary detention, torture, and other abuses masked under the premise of protecting public order that risk the fate of Tissainayagam befalling anyone today, and likely for far less contentious content.

Expanding on this, I quickly ran through some of the more obvious points around the potential for political misuse, and partisan abuse of the Act. Overly broad definitions of “prohibited statements” and “false content” give authorities unchecked discretion to censor dissenting narratives, and inconvenient truths by deeming them “false”, “dangerous” to public order, or “promotes feelings of ill-will”. Given the country’s history of targeting Tamils, and Muslims, the Act risks being exploited to disproportionately target members of minority communities, activists, journalists, and political opponents under the guise of hate speech, and national security. Increased surveillance powers, arbitrarily employed, will lead to harassment of those who highlight, for example, corruption or graft. Arbitrary website and online platform or account blocking abilities will severely impact Sri Lanka’s information environment, shrinking public discourse, and constraining public debate to circumscribed issues, subjects, topics. The lack of robust independent oversight, heightened by the incumbent President’s profoundly worrying stance on the Constitutional Council worsens the ability of biased appointees (who will invariably be apparatchiks) to influence findings aligned with ruling party objectives. I noted the Act’s strategic vagueness also enables limitation of online advocacy, and campaigning during elections that authorities may argue threatens “public order.” Individual politicians, including ruling party MPs may pressure officials to investigate, and limit online commentary, and social media content critical of them, debilitating opposition campaigns.

Relatedly, I noted the OSA leaves open, and expands the potential for so-called “dark signatures” online, which include surreptitious coordinated online reporting campaigns aimed at censoring opposition voices by proactively orchestrating OSA violations. By flooding rival media platforms, opposition social media accounts, or the comments sections, and social media replies of critical mainstream outlets with violative comments produced by bots or even armies of clandestinely paid individuals, bad-faith actors including those from, and aligned with government can prompt investigations, and restrictions of their targets under the OSA’s overbroad prohibited speech definitions. This weaponisation of the Act’s provisions will likely have severe, and sustained chilling effects, ironically worsening online harms, especially against women in or seeking public office, the legislation ostensibly tries to limit.

In short, I noted the OSA risks becoming a blunt force tool for the ruling party to silence opponents through manufactured, performative public outrage, and the über-regulation of all forms of online speech, in English, Sinhala, and Tamil. The ability of government to develop an adversarial, censorious legal framework based on partisan, and politically-motivated interpretations of the OSA’s provisions I flagged as core threat to Sri Lanka’s democracy.

Set against this parochial, partisan interpretation of the OSA by government – already a reality – was what I flagged were pervasive, and persuasive FMIO operations in Sri Lanka. Primary research on China’s influence operations instrumentalising Facebook highlighted the already sophisticated “design, execution, and impact of Beijing’s multi-platform, multi-media, vernacular, and country-specific propaganda model” (going far beyond ‘wolf warrior diplomacy’ on Twitter).

Although there’s zero interest in it from the Sri Lankan state, combatting this requires domestic legislation in harmony with, amongst other things, how a platform like Meta defines, and defends against Coordinated Inauthentic Behaviour (CIB). In comparison to how it is defined in the OSA, Facebook’s definition focuses more narrowly on deception about identity or origin for ideological or financial motives. As per their explanation, CIB involves groups of pages or people working together to mislead others about “who they are or what they’re doing”. On the other hand, the OSA defines CIB more broadly as “any coordinated activity carried out using two or more online accounts, in order to mislead the end users in Sri Lanka as to any matter”. So while Facebook centres its definition on deception about identity/origin specifically, the OSA’s definition covers coordinated activities to mislead users about any matter at all. Given this definitional divergence, one implication is that Meta will not be able to service any request from the government to look into CIB. In any case, given serious questions around the constitutionality of the Act, and severe impact on human rights, all leading online platforms will simply refuse to service OSA-based requests from government.

What this essentially means is an environment ripe for exploitation by foreign actors, including those conducting FMIO, who have a vested interest in shaping political rhetoric, the public imagination, and electoral outcomes around parties, and candidates favourable to them. While they will be able to operate freely, measures to study, surface, and thwart their influence will suffer because of the OSA. It’s beyond farce, and gets worse.

Based on primary research into Sri Lanka’s surveillance architectures for over a decade, I noted the OSA may result in internet service providers, and technology platforms (both domestic, and foreign) being compelled to collect, and share Sri Lankans’ personal data, and private communications with government agencies at an unprecedented scale. Authorities could potentially track all forms of online activity including SMSs, person to person instant messages, group messages, emails, social media activity, and uploads to any cloud service in the name of monitoring for “prohibited content.” This puts the OSA at significant odds with the Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA), which is already facing partisan headwinds. The OSA grants a government commission expansive authority to monitor online content and communications with minimal transparency, accountability, or independent validation safeguards as seen in PDPA’s governance standards. Additionally, the OSA allows state regulators to block websites based on vague prohibitions, restricting public digital access and discourse. By contrast, PDPA focuses singularly on securing citizens’ data protections and privacy rather than compromising rights through opaque speech controls, and unchecked surveillance authority. The sweeping expansion of state power to access user data and restrict online information permitted by OSA, contrasts directly with PDPA’s purpose to protect consumer privacy, and digital rights. It is unclear how, and if these tensions will be resolved. Meanwhile, sensitive personal information in the hands of security, and other state agencies will be used to track, trace, and target activists, journalists, opposition figures, and other dissenting voices for state harassment or arrest. Knowing that their online activities will likely be constantly monitored, citizens will likely increasingly avoid discussing sensitive or political topics, leading to self-censorship, and a significant chilling effect.

A question from an audience member around whether young people like him would be targeted under the OSA was instructive in this regard. I noted that it was likely they will be, but not necessarily because of what someone posts online on a specific issue, but based more on the virality of the content. This vital aspect will be a critical determinant in how the OSA will be weaponised, connected to what social media studies term “long-tail effects”, highlighting how content first posted or published months, years or even decades ago can, through re-discovery, and re-publication lead to significant, and sometimes sustained spikes in engagement. The discoverability of material from the past, even first published in an obscure location online can serve to embarrass officials, and those in power, leading to the OSA’s immediate weaponisation against the original content producer if they can be found, or those who found the old or original content, and made it go viral. The implications are profound, impacting all cultural, and media production.

Although I didn’t have the time to go into it – and even here, am restrained by length to capture fully – I also flagged how the OSA doesn’t address threats to democracy, social cohesion, and electoral integrity brought about through generative AI. Connected to the point about around targeting platforms, and accounts of the opposition, generative AI allows for the creation of synthetic media, including deep, and shallow fakes at an industrial scale. The implications of this will be felt over 2024’s electoral moments, and ironically, will be worsened significantly by the OSA’s implementation.

And it’s around this specific point dealing with the OSA’s implementation that I said statements by the Australian, and British High Commissions were deeply problematic. The Australians suggested implementation of the OSA was somehow possible “in accordance with international best practice and standards”, while the British said the OSA should be implemented preserving “Freedom of Expression and on Sri Lanka’s economic growth”. These tweets were regrettably extremely ill-informed, with calls for the “balanced implementation” of the OSA falsely implying some compromise can be reached between the preservation of civil liberties through regulatory discretion despite legislation that’s censorious by default, and design. It’s even more farcical to think of any rights respecting implementation of the OSA within Sri Lanka’s political culture, including the complete, public disdain for human rights by the same Minister the OSA’s implementation will fall under. Allowing unchecked surveillance, arbitrary blocking authority, partisan appointees, and subjective public order interpretations do not, and cannot co-exist with a rights-respecting democracy, and I tweeted “giving hope it can is misdirected, and affords the SL govt interpretive space to say they can, helping establish autocracy.”

I ended the BALPP presentation on a tragi-comic note, and said that for the sake of argument, I was willing to accept the government wanted to project children, and women from pornography. No matter how flawed, given the Attorney General’s role in the pre-enactment review of legislation, and what will be an on-going role around the post-enactment implementation of the OSA, I noted how the Attorney-General’s official website was itself a cogent example of how bad relevant technical expertise within government was.

The Attorney General’s website, aside from official content, is currently concurrently hosting e-commerce platforms which ostensibly openly sell what should be age-restricted, sexually explicit material including sex toys and BDSM items, pornography, general supplies like homeware, kitchen utensils, pet food, garden equipment, and far more disturbingly, guns, weapons, and even ammunition. What I said shocked even fellow panellist Prof Goonesekara, and many in the audience. And as incredible as it sounds, it is truly this bad, and independently verifiable. That no one in the entire Sri Lankan government, including SL-CERT, and the AG’s department is remotely aware of the degree to which this website is horribly corrupted, and hopelessly compromised raises serious questions around how the government intends to go about servicing complex, technical phenomena like CIB as part of the OSA. The only honest answer to this question underscores what I noted at the start of the BALPP lecture, and this article.

The OSA isn’t about children, women, or pornography. It provides government unprecedented legal cover to quash online organising, and activism against cronyism, corruption, injustice, and a democratic deficit. The Act will be weaponised even more in the future to suppress any hint of another aragalaya-type moment, and movement.

The repeal of the OSA should be a clarion call of, and core campaign pillar for all opposition parties, and presidential candidates. The Act is a party blind democratic threat. No one who supported the OSA should be forgotten, or forgiven, including an incumbent President who realises at pace the worst of what the aragalaya rejected, and sought to reset. It isn’t an overstatement to say the future of Sri Lanka’s democracy rests on the repeal of the OSA. Anything less will be an accelerant for autocratic expansion, and entrenchment.