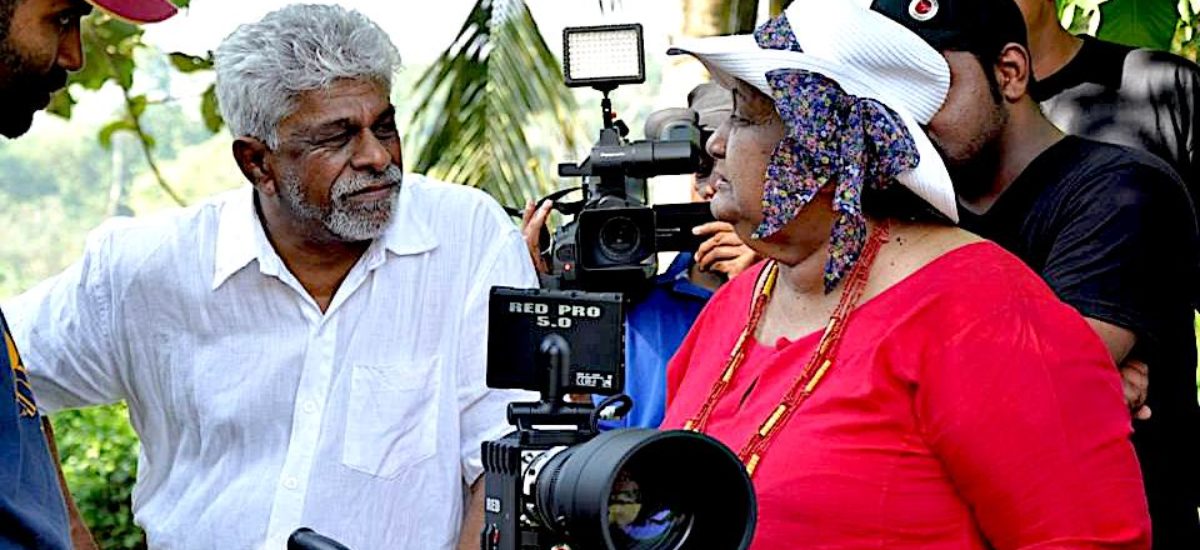

Photo courtesy Uditha Devapriya

The French Embassy screened Vaishnavee at the National Film Corporation, the last in a series of cultural items commemorating the 75th anniversary of diplomatic ties between France and Sri Lanka. The finale was, to put it rather mildly, a fitting one. Sumitra epitomised Sri Lanka’s French connection in ways few of her contemporaries did. A Francophone and a Francophile, she represented the country there in the late 1990s. As a student in the 1950s, she found herself stranded in Paris, before being whisked off to the French Legation, headed then by Vernon Mendis. It was there that she met Lester Peries and there that she saw her first real Sinhala film, Rekava.

That French connection was revived on Tuesday evening. Yet although a fitting finale, it was also a sombre affair. Sumitra’s passing earlier this year represented not the passing but an end of an era, an era that began its descent with the passing of her husband in 2018. It was in that year that Vaishnavee was first screened publicly in Sri Lanka. Based, as the titles inform us, on a story by Lester, Vaishnavee represents Sumitra, if not at her finest, then at her most characteristic. Like Ray, Antonioni, and Kurosawa, Sumitra’s last film is a celebration of innocence, not a mundane reflection on serious themes.

Watching it at a private screening in 2017, I went back to Pauline Kael’s review of Ghare Baire. “The main characters talk, and the camera just stays on them and waits until they finish, yet these conversations develop a heart-swelling intensity. In a scene, the method is like that of amateur moviemakers who think that all they need to do is put actors in a room and photograph them reading their lines as if they were on a stage. The difference is that Satyajit Ray… didn’t start with this simplicity – he achieved it.”

It would be anachronistic to apply this to Vaishnavee, a film which unfolds in a different world and universe, a different time. But like Satyajit Ray in 1984, Sumitra had by the time of her last film been making movies for 30 years and another 10 years as an editor, mostly for her husband but for other directors as well. Vaishnavee is full of sequences that seemingly go nowhere: a kindly uncle talks about the future with his orphaned nephew; the nephew’s fiancée elopes with a man we never hear of again; the jilted lover is then taken to another prospective bride, who turns out to be a disappointment. These are of peripheral interest to the storyline. But they are intriguing enough on their own. And they bear the signature of a director who has been at it for so long.

Reviewing Walt Whitman, Randall Jarrell wrote of a poem, that “there are faults in this passage, and they do not matter.” There are enough and more faults in Sumitra’s film. These, however, do not really diminish the story; rather, they add to it. As I noted in my first review in 2017, the conclusion bothers me somewhat. It is trying to tell us something about the eternalness of love, about the fact that love should never be taken for granted. But the Pygmalionesque overtones (or undertones) of the narrative outweigh everything in the story. This is not to demean Yashodha Wimaladharma’s performance. But the final scene between her and the protagonist seemed too ambivalent, too abrupt.

The Sumitra Peries film that Vaishnavee evokes best in this regard is Sakman Maluwa. There too, love is expressed ambivalently, until in the end the characters reach a catharsis when the wife plaintively tells the husband that only he can bridge the gap which has sprung up between them. In Vaishnavee there is no bridge to pass over; the puppet, right after her metamorphosis, turns the tables on the protagonist by making it clear that she will not be taken for granted, not even by the person who moulded her.

When I went to its first screening in 2017, I was asked to bring my mother along. “She will appreciate it better, I think,” Sumitra suggested. I saw her point at once. Vaishnavee recalls a tradition of filmmaking that has all but completely been lost. Yet the message in the story is relevant for all time and it resonates particularly sharply with the younger crowd as well, particularly the women, who would notice how deftly the director has subverted the Pygmalionesque outlines of the story. In George Bernard Shaw’s play, the flower girl, taught to be a lady, laments that she can’t be anyone other than a lady. She realises the limits of her new situation but can’t do anything about it. In Vaishnavee on the other hand the puppet that is brought alive refuses to be confined to any situation. She strikes back at her creator. Instead of being grateful to him, she haunts him and his family.

This does not make the woman a neurotic Glenn Close type who will go to any length to have the man who chose to breathe life into her. There are, to be sure, times when one feels that she is taking things too far, especially when she haunts the protagonist’s cousin. But even when the likes of Rohana Beddage gather around and try to exorcise her from their home, even when the protagonist – played by an impeccable and pre-Koombiyo Thumindu Dodantanne – has our sympathy, you understand where she is coming from and why she is acting the way she is. She feels wronged, slighted. Although we don’t see everything from her point of view, we understand her motives, especially in the conclusion where she cautions the man against taking love for granted.

To be sure, the fault isn’t the man’s. He clearly loves this woman. Yet he can’t bring himself to do so because his world is not hers. But in another film, the woman would have made the effort to prove herself worthy of him. This is not that movie. Instead the woman makes it clear that she cannot be dismissed, that the man cannot call the shots over her. One can consider Vaishnavee a feminist work in that regard. The director, rather than sticking to the traditional girl hankers after boy arc, chooses to subvert it.

This is hardly surprising. Sumitra’s films have always been about women refusing to be who they are defined as being by the rest of the world. From Vasanthi Chathurani in Gehenu Lamayi to Swarna Mallawarachchi in Sagara Jalaya, to Geetha Kumarasinghe in Loku Duwa, there is an incipient rebelliousness in her women. Sometimes they manage to rise above their situation, often they don’t. What Sumitra does in Vaishnavee is to add a supernatural twist to this theme and bring it up to date for newer, younger audiences.

Much has been written about Vaishnavee’s “magic realist” credentials. Magical realism is defined as a mode of art which depicts a realistic picture of the world while adding or incorporating magical elements. There is here a near complete erasure of the line between these two qualities. To the extent that it incorporates realistic settings and magical aspects, Vaishnavee is, in that sense, magic realist. Moreover, in a story teeming with special effects, the realist elements themselves occupy another world. The talking parrot, for instance, is very much “real”, but it is also somewhat otherworldly. Yashoda’s character is another case in point. Even after entering our world, she retains her supernatural elan.

Other Sinhala films have tried, although not always successfully, to bridge the gap between magic and realism. One invariably recalls Udayakantha Warnasuriya’s Ran Kevita and Ran Kevita 2. Yet these were children’s films, which brimmed with an innocence that could easily be squared with the simpleness of their themes. Sumitra’s film, on the other hand, is not an innocent film, although it too brims with innocence. One may be taken in by its old world charms – in a film that evokes birth and rebirth from start to finish, in only one scene is there a real hint of death, the protagonist’s attempt to cut his wrist after learning of his fiancée’s elopement – but there is a profoundly serious theme hidden beneath. The supernatural occurrences, in that regard, are not cosmetic; they grow out of the puppet’s feelings for the protagonist and the protagonist’s ambivalent response to them.