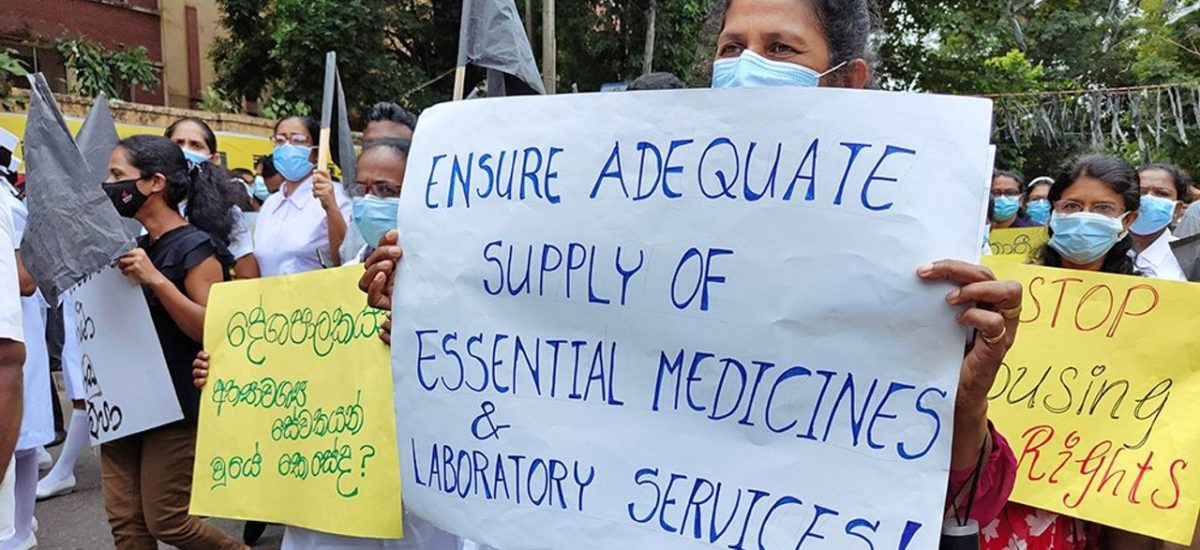

Photo courtesy of WSWS

Sri Lanka’s health system continues to face extreme challenges in the aftermath of the economic crisis and continued lack of health system strengthening. While some of the urgent threats such as power supply interruptions have been allayed, many challenges remain. Even though health system challenges may phase out of the headline grabbing sensationalized news cycles, it is vital that we keep a focus on what is killing our health system slowly. The double impact of a rapidly deteriorating health system and worsening living conditions affect education, workforce availability and general quality of life all Sri Lankans.

The health system and interconnected health challenges of the population face multi-pronged threats. In this article, we list three key threats to the health system and important contextual factors that worsen health outcomes. Most of these challenges urgently require systemic, anti-corrupt and transparent policy solutions.

Unresolved and continuing drug shortages

The impact of drug shortage has been widespread and has been highlighted by many researchers and practitioners since 2022. In November 2022, we highlighted how Sri Lanka in addition to systemic failures, was faced with key drug shortages including those required for essential surgeries. The drug shortage continues to impact Sri Lanka’s population with inadequate supplies of essential medicines in state hospitals as pointed out by health professionals. Recent media reports highlighted the absence of meningococcal vaccines in the state sector for Hajj pilgrims, which have led to improper importation of vaccines without proper cold chain management. The impact of drug shortages especially affects vulnerable populations in Sri Lanka who cannot afford to pay premium prices for medicines. In the event of a pandemic or an epidemic, having a well-supplied health system is instrumental to provide effective healthcare to people.

Poor quality medicines and unregulated importation

Interconnected to the drug shortage challenges is the importation of poor quality medicines that put the health of our communities in danger and also contribute to erosion of trust in our public health system. Earlier this year there have been globally recognized challenges of such as contaminated, low quality cough syrup causing deaths among children in seven countries. In Sri Lanka there have been reports of loss of vision due to poor quality prednisolone eye drops in Nuwara Eliya Hospital among several other hospitals. Also patients died following the administration of bupivacaine (anesthetic drug) that have been imported bypassing the National Medical Regulatory Authority (NMRA) registration. These batches of drugs were subsequently withdrawn and two out of three such batches later failed the quality checks.

Political determinants have played a significant role in challenges related to poor quality medicines. As an investigative report published on Sunday Times has highlighted, there are some gaps in the Ministry of Health investigation report. One of these gaps is that the investigation only focused on allergies (two cases) out of the 15 cases in consideration. Following these deaths and news reports, in addition to recommendations to prevent anaphylaxis the expert panel also emphasized the need for increased diligence in evaluating the quality of medicines during registration and post-marketing testing of random samples for quality. Earlier this year, there were questions around the Health Minster’s involvement with drug companies and trip funded ‘by friends’ to meet drug manufacturers in India. In February 2023, all the major professional bodies in health wrote to the president vehemently opposing the suggestion by Minister of Health, Keheliya Rambukwella, to bypass NMRA registration due to health risks to patients. Last week, the no confidence motion against Keheliya Rambukwella was defeated in the parliament although many of the health crisis challenges remain.

Migration of healthcare workers due to crisis

Healthcare workers whose generosity and dedication have contributed to making Sri Lanka’s health system one of the strongest in the region are facing dire challenges as well. As a result, many are opting to leave the country due to unresolved shortages of medicines, rise in toxic working conditions and deteriorating living conditions. The narrative of this crisis as healthcare workers betraying the country, as reported by some media outlets, tends to ignore the complexity of this challenge. It is important to remember the government in late 2022 encouraged healthcare workers to seek work outside to earn in foreign currency.

Demonizing healthcare workers in an already increased workload context is not an effective policy solution. On the other hand, strengthening the health system including addressing shortages and creating better support for healthcare workers including ways of delegating tasks will improve the quality of care. As it is a basic human trait to care for your own families and to secure a better future for children, it will be important to create better living and working conditions for all, including healthcare workers, to mitigate the exodus of skilled workers.

Contextual factors have deepened challenges

As the health system faces key challenges highlighted above, there are several key contextual factors that demand our attention. Our non-communicable disease burden continues to become worse with latest studies reporting 23% of diabetes prevalence, higher than any country in the Asian region. Non-communicable diseases affect our growing ageing population and with a weakening health system, the healthcare of our elders will be at risk. Contributing to this challenge is the seasonal recurrence of infectious diseases such as dengue. Sri Lanka faced a severe outbreak of dengue in the first two quarters of this year and as of August 2023, there were over 55, 000 cases reported. Additionally, the world is watching the emergence of a new Covid-19 variant (BA. 2.86) which has the ability to even re-infect those who are vaccinated and those who had contracted the virus before.

The often raised rising malnutrition challenges have been ignored, especially those affecting children and interconnected poverty impacting urban and rural poor. The nutrition dashboard of the Family Health Bureau indicated that percentage of under five children who are underweight has increased from 13% in 2022 to 16% in 2023 June. A recent report by LIRENasia identified that 31% of the country are now below the poverty line with four million people newly falling into poverty during the last few years.

Given the above challenges, the interconnected political and economic realities, Sri Lanka will need to put forth clear strategic policy changes and eliminate space for corruption. As we face rising rapid changes caused by climate crisis, multiple disease burdens posing risk to our most vulnerable including children, elderly and the poor, clear policies that act upon evidence should be the only way forward. As election cycles loom, the easy response would be to create enemies such as healthcare workers. However, misguided short term actions and policy inaction will cost lives of Sri Lankans.

Shashika Bandara, is a doctoral candidate on global health policy and governance at McGill University, Canada. He was formerly a policy associate at the Center for Policy Impact in Global Health at Duke University.

Inosha Alwis is a physician and researcher, and a lecturer at the department of community medicine at the University of Peradeniya. His research interests are health systems, health promotion and public mental health.

You can read their related editorial on health crisis in Sri Lanka published in the BMJ on November 29, 2022.