Photo courtesy of Quora

“For Sri Lanka, everyone is important.” Ali Sabri

“We lack democratic accountability and transparency in our dealings with the world.” Dr Ranga Kalansooriya

Speaking in Parliament in 1996, Anura Bandaranaike dwelt on the legacy of his father and mother. He spoke of how the world had viewed Sri Lanka in their time and how it was being viewed in his. “We have nothing to be respected for,” he argued. “We are an unimportant Third World country where we are killing each other. The respect that Sri Lanka enjoys, the respect that all of you gentlemen enjoy when you go abroad, is because of the foreign policy that was started by my father and which was taken to its logical conclusion by my mother.” It hardly needs adding that Mr. Bandaranaike made these remarks as an opposition MP, when his sister was the country’s president and his mother its prime minister.

Sri Lanka used to be influential. It used to matter. In 1996 it was 20 years into a separatist conflict that had sapped it of its brightest minds, many of whom had been killed and many others who had emigrated. Nearly 30 years on, it remains smaller than ever. This is, at one level, an unpalatable truth. But it is the truth. Viewed in retrospect, Mr. Bandaranaike’s remarks thus seem not just prophetic, but inevitable. It’s almost as though Sri Lanka could never go up, as though it could only go downhill. We certainly no longer court the respect of the world. We clamour for it but have precious little to earn it.

What explains this curious contradiction between what Sri Lanka could be and what it is? Commentators would point at its size. However, Sri Lanka is not the only small state out there. There are other small states, many of which are smaller than even us, that have done better. By dint of their size, these countries do face certain challenges: many of them lack agency and have to engage very proactively with powerful players. Sri Lanka’s dilemma, in that sense, lies in its location; separated by 55 km from the Indian subcontinent, it remains locked into the intrigues and tensions that have come to define the geopolitics of the Indian Ocean. Our choices are limited: we can do only so much on our own and even that is circumscribed by external factors.

But Sri Lanka’s smallness did not always circumscribe or confine it. Mindful of its position in the Indian Ocean, successive administrations pursued different strategies to reinforce its place in the world. Some of these strategies paid off while a great many others backfired. Needless to say, its domestic politics had an indelible impact on its foreign policy. The D.S. Senanayake government’s Cold War alliances in its immediate post-independence period, for instance, were what influenced it to singlehandedly deprive an entire ethnic group, the Indian Tamils, of citizenship. This, in the long run, provoked a backlash from India, which not only lent support for the formation of the Ceylon Workers’ Congress (CWC) but, over the years, led to a deterioration in relations between the two countries.

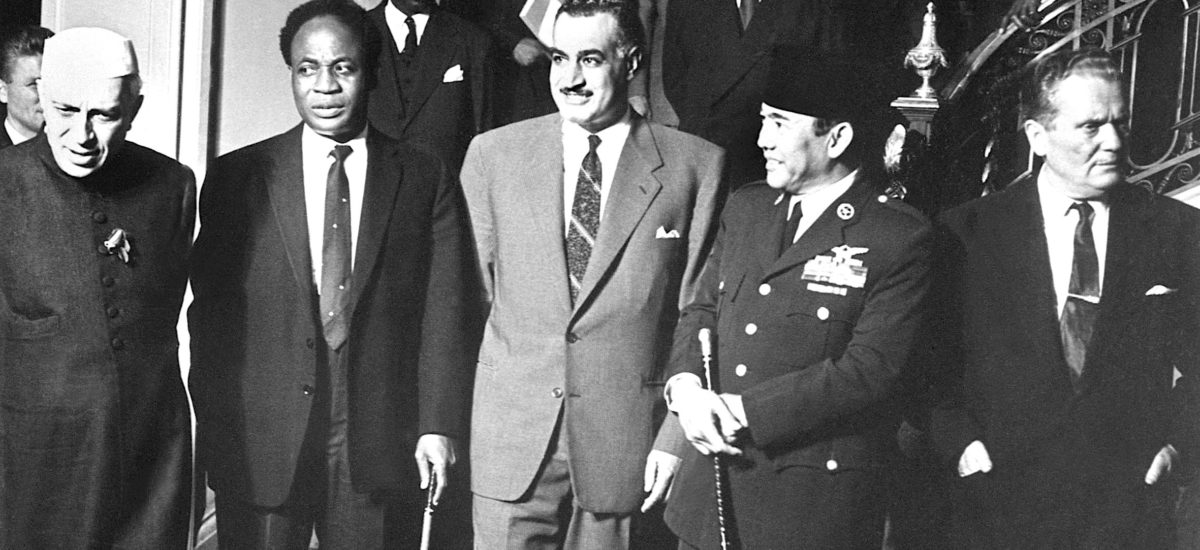

What salvaged Sri Lanka during these years was its adoption of nonalignment as an official foreign policy. One must, however, be mindful when talking of nonalignment. Today, both nonalignment’s critics and champions view it as a morally neutral, indeed amoral, principle, which serves to distance Sri Lanka from the rest of the world. Yet as Prime Minister S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike himself put it in 1956, nonalignment by no means entailed a neglect or an abandonment of Sri Lanka’s moral responsibility in the world. It instead denoted an attitude of dynamic neutralism: its main function, as the Bandaranaikes sought to emphasise in word and deed, although not always successfully, was to steer clear of power rivalries while taking an active part in world affairs. This is the nonalignment which Sri Lanka pursued, even as its leaders took a lead in defusing tensions between India and China and pursued initiatives like the Law of the Sea and the Indian Ocean Zone of Peace.

To put it simply and bluntly, Sri Lanka’s political and diplomatic elites have come to view nonalignment as a ballast, even a justification, for their diplomatic and domestic political failures. Whenever the country faces human rights allegations, instead of engaging constructively with such allegations, its leadership chooses to summon the bogey of Western intervention. Whether in Colombo or in Geneva, it speaks of values like human rights and democratic accountability as convenient tools of Western imperialism. But there is a very fine line to be drawn between critiques of the way such values are deployed against some countries and not so against others, and the view, widely held by political elites in the Global South, that human rights itself is expendable and need not be promoted.

For better or for worse, nonalignment has become a save face strategy for these failures. Rather than addressing the elephants in the room – including the biggest one, the national question concerning Sri Lanka’s Tamil speaking minorities – our political elite has instead turned a very progressive concept and principle into an opportunistic, short termist tactic. The country’s conduct after the end of the 30 year separatist conflict is the biggest case in point here. The military “victory” in 2009 was eventually followed by a diplomatic victory, but the promises we made to India and the world at large were never implemented or even investigated. Instead a temporary triumph, which is what Sri Lanka’s defeat of the UNHRC resolution in 2009 amounted to, enabled triumphalist elements to gain control of the narrative, contributing to a deterioration on every front: ties with India, with the West (duplicitous as it may be over human rights) and with our own people.

Whether such policies are sustainable and whether the Sri Lankan political leadership’s narrow minded conception of them has contributed to Sri Lanka’s diminished stature in the world today, is self-evident. During the Cold War era nonalignment was deployed, rather expediently and justifiably, against Western imperialism. In the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union, important debates have sprung up whether Western imperialism is, in fact, the only form of imperialism we have at present. The Sri Lankan political leadership, in this regard, has pursued a dual strategy: it speaks valiantly of and against Western imperialism yet has pursued policies that reinforce its dependence on Western markets and economies. Fundamentally an exporter of tea, trade and tourism, not to mention dirt cheap labour, the country remains lodged between a rock and a hard place here.

This is what has brought Sri Lanka to a Mexican standoff today. The country continues to rage against what it sees as Western intervention, while doing nothing to engage with such challenges. Its preferred strategy has been to ignore or neglect diplomacy in its relations with powerful states. The country’s small size by no means excuses such failures, primarily because other countries have benefitted from diplomatic engagement; here I am not just thinking of success stories like Singapore, a city state which gained heavily from fortuitous circumstances like the US’s Cold War policy in South-East Asia in the 1960s and 1970s but also the much battered Vietnam, which not only enjoys a strategic partnership with China, but also has formed important relationships with Western countries.

The simple answer to the question why Sri Lanka has gone down in stature is that we have never really been honest with our dealings with the world. We cannot use our past to justify our present failures. And yet that is what we been doing. From the unilateral ban on the Qatar Charity to the fiasco over COVID-19 burials, we have avoided the responsibilities we owe to the rest of the world. We have gone as far as to exploit nonalignment and legitimate criticisms of Western imperialism, and Western intervention, to sidestep our responsibility to our own people. In doing so, we have, as Dr Ranga Kalansooriya noted in a recent speech, not been accountable to and transparent even with our allies.

Foreign Affairs Minister Ali Sabri recently remarked at a book launch that for Sri Lanka, everyone is important. This is a highly relevant statement. It may even be considered as the official foreign policy of this government. Yet if everyone is important, we cannot afford to alienate anyone. Regardless of what we think of other countries and power blocs, we are no longer the major small player we once were in the world. We cannot move mountains. The first step towards repairing our bilateral relations and our multilateral engagements, hence, is to recognise how badly we have regressed and do everything in our power to set things right. To do that requires a resolve to see things through. Whether Sri Lanka and its political and diplomatic elites possess that resolve remains to be seen.