Photo courtesy of Daily Mirror

We are living in a critical zone. Have you ever thought of the critical nature of the zone that we live? Probably not; we take the earth that we live on for granted and we do what ever we want with it. The critical issues about this zone were the focus of a recent exhibition Critical Zone. In Search of a Common Ground held at the JDA Gallery co-produced by the ZKM | Karlsruhe and the Goethe Institute/ Max Mueller Bhavan Mumbai.

When we consider the earth, it is only a small portion in the universe and our life depends on few hundred meters above the ground level and few hundred meters below the ground level. Many interactions take place within this area to determine the nature of the earth. The living organisms and the nature can influence this area in various ways. This small area in the universe is termed the critical zone. This is the zone in which life can exist and known to exist.

The critical zone is the earth’s permeable near-surface layer from the tops of the trees to the bottom of the groundwater, according to the US National Critical Zone Observatory of the National Science Foundation. It is a living, breathing, and constantly evolving zone where rock, soil, water, air and living organisms interact.

How does the critical zone form? How does it function and how will it change in the future are fundamental questions with no definite answers. Scientists the world over are trying to understand the critical zone in bits and pieces. Because the complex nature of interactions involved in regulating this natural habitat in terms of maintaining life sustaining resources such as food and water, it is not possible to develop a holistic scientific approach to unfold this complexity.

The critical zone is continuously undergoing changes due to weather changes, activities of the organisms and activities of the humans. Some changes may enhance the livelihood of living beings, some may be detrimental to life forms and some may be detrimental to the critical zone itself.

Scientists are working on various aspects of critical zone in networks involving universities, research institutions, governments and international bodies. Philosophers such as Bruno Latour have come in with their new approach to find a place for arts and aesthetics in this complex issue of the critical zone.

This zone has been altered throughout ages by various factors. But the damage was profound and rapid after 17th and 18th centuries. The period during which maximum damage had been done to the critical zone has been a contentious issue among social theorists, scientists and philosophers. To identify the period, Latour proposed the term the new climatic regime, which could be regarded as an alternative to Anthropocene, a geological nomenclature that has been disputed among scientists. The ecological damage is a significant challenge for all countries and to address the issues requires some changes in our legal, political, mental and literary organizations.

According to Latour, we are not sensitized to this new climatic regime. He argues that there is science, without which we would not have become aware of the change, and there is politics, which assembles the relevant stakeholders. But in addition, there is the arts. We don’t seem to be endowed naturally with the right sensitivity to absorb the magnitude of the ecological mutations that have taken place although we have the scientific knowledge of this mutation. Latour sees these three elements – science, politics and arts – as aesthetics that help us to become sensitive to the ecological issue.

The human race’s thinking and philosophy of life has changed over time. With this there was change in humans’ relationship with nature and other living beings. Latour insists that modernism has separated nature from culture, science from politics and objects from subjects. Modernism has also launched vast technological interventions that prompted a proliferation of hybrids that cut across such divides. In arts, modernism has created a detached sense and alienation from reality. It created a separate world for the artist on his own terms, targeting an utopia.

With modernity the connections between humans and non-humans grew in both scope and intimacy. The environmental crisis brought about by scientific advancement during modernism never led to real development but only to ever increasing entanglement.

Latour wanted to bring this scientific truth closer to mankind. His collaboration with Peter Weibel, a prolific author of books on theory and director of the Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe who declared that art’s main interest no longer centers on beauty but on media, provided him with a good launching pad for his theoretical ideas through art.

Peter Weibel invited Latour to challenge habitual thinking with a thought exhibition in keeping with Weibel’s view of exhibitions as places for experimentation, dialogue and reflection in contrast to the politics and vested interests conveyed through mass media.

However, labelling the thought exhibition simply as an illustration of theory underestimates the potential of these types of exhibitions. Art is not a medium to impart insight and knowledge in its own right and it does not function as an independent source to align aesthetic language with science without curatorial intervention.

Latour’s last exhibition in collaboration with Weibel, Critical Zones. Observatories for Earthly Politics, was conceived and exhibited at the Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe. The South Asian adaptation of which was termed Critical Zone. In Search of a Common Ground focused on sensitizing people on the scientific facts that are emerging regarding the precarious state of the earth and the critical zone we inhabit along with other organic and inorganic matter.

Latour’s exhibition had five sections; Starting to Observe: A Critical Zone Observatory; We Don’t Live Where We Are – Ghost Acreages; We Live Inside Gaia; Redrawing Territories; and Becoming Terrestrial.

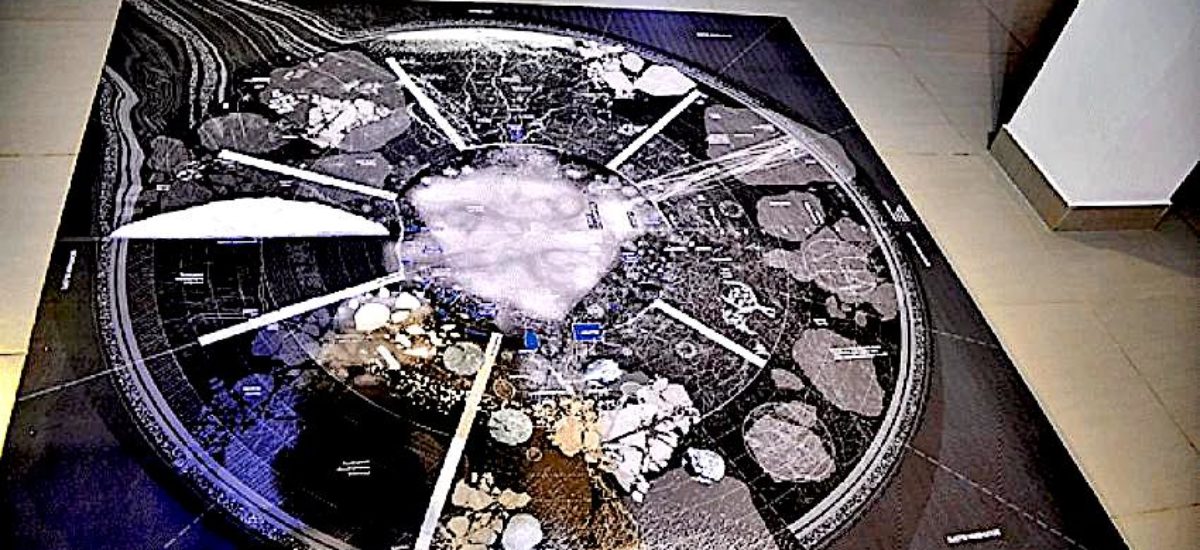

The first section was about the Critical Zone Observatories (CZO) that monitor the different parts of the fragile and complex domain of the critical zone. This is to observe how the critical zone functions and how it will be altered in the future. A thematic map was presented to show a set of data to illustrate the geographical spread and distribution of inorganic and organic nature. There were illustrations of chemical cycles that operate in nature that connect organic and inorganic matter. A main artistic work was a virtual reality immersive experience to view a possible atmospheric forest we are heading to due to climate change.

The second section was about the soil that gives our prosperity. This area is denoted as ghost map or a map of ghost acres that extends much further in space and in time than a topographical map and includes the extent of international commerce, colonial past, the lands producing our energy resources and other invisible life forms related to our life.

The third section was an effort to illustrate how other living forms contribute to make the critical zone habitable and to show that humans have to act in ways to make it habitable to other life forms rather than destroying it.

The fourth section showed how humans define boundaries to safe guard sovereignty but natural disasters and events have no respect to man made boundaries. Man made toxic chemicals and fumes travel across boundaries to harm live forms. Hema Shironi’s historical mappings of Sri Lanka from the 4th century BCE to the present are shown as embroidery maps to convey messages on how the map of Ceylon has changed to express power, politics and expression of identity.

The fifth section of the exhibition makes us take stock of our present state and not to see human race as divided by various factors but to establish a new common ground. We have to recognize that each entity is organic and inorganic and has a place and a vital role.

The exhibition is not a stand alone phenomenon in the arts. The emphasis on collaboration between science, technology, engineering, maths and arts is increasingly felt in many fronts globally. This year there were 10 major art projects commissioned by the United Kingdom to promote cross sector creative collaboration between people from the science, technology, engineering, arts and maths sectors.

There is a push to promote arts to be included with other fields for meaningful development of human race in the future. Aesthetics as we understand also needs to undergo a drastic change.

Human beings need to be sensitized about the reality of our existence. This is probably the time to redefine the role of art through a philosophy of existential aesthetics to emphasize what is essential for the future existence of the critical zone as a habitable zone.