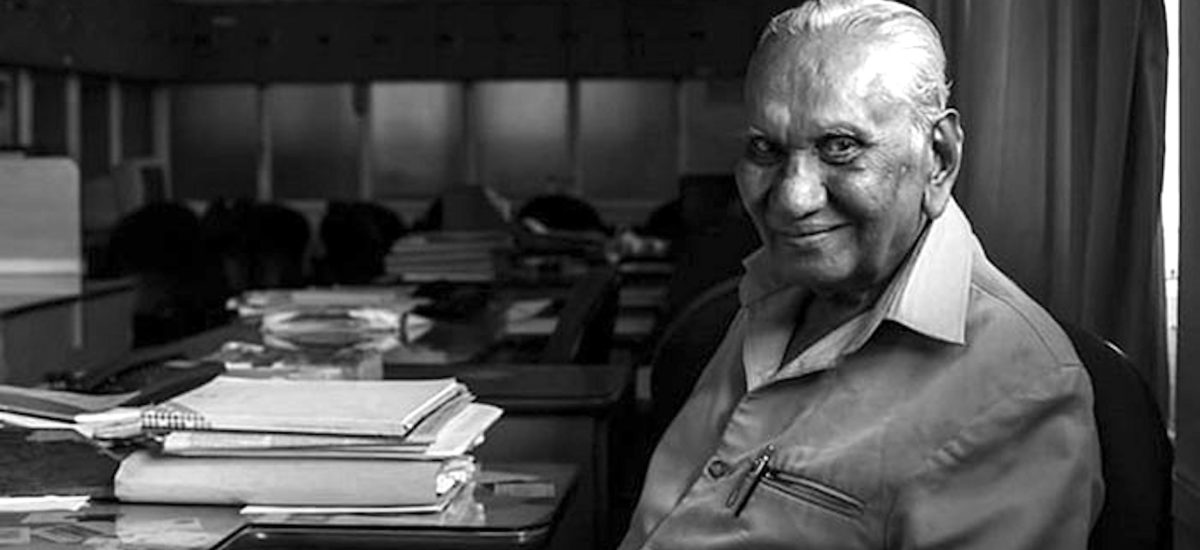

Photo courtesy of Kannan Arunasalam

“If I can stop one heart from breaking, I shall not live in vain;

If I can ease one life the aching, Or cool one pain,

Or help one fainting robin, Unto his nest again,

I shall not live in vain.” Emily Dickinson

Edwin Ariyadasa, born on December 3, 1922, would have turned 100 this past weekend. While he was a giant and a pioneer in journalism in Sri Lanka, this reflection is not about his achievements. It is about the ethos of compassion that drove him to be who he is, that guided his commitment to communication and to help others even when it was disadvantageous for him.

First, as a disclosure, I am writing this both as a Sri Lankan and as his grand-nephew since Edwin Ariyadasa is my grand uncle known among us affectionately as Sudu Seeya. Second, I am writing this because I thought a reflection on compassion and its uses by a recognized genius may resonate with many and inspire some in our communities, especially as we battle unprecedented times of struggle.

Before delving in to pay my respects to his illustrious career and pioneering spirit, I want to highlight few of his achievements: Edwin Ariyadasa joined Lakehouse publications on March 3, 1944 and was the editor of many publications also appearing in numerous television and radio shows. He has received one of the highest honors in Sri Lanka Deshabhandu for his services to journalism, he created and taught the first ever mass communication syllabus in Sri Lanka at the University of Kelaniya, he was awarded Kala Keerthi for his services to arts, culture and drama in Sri Lanka, and he has created many print and media programs on science communication. Perhaps his most treasured publication, one he talks about often with deep fulfillment, is his editing of the illustrated Dhammapada, which was published under the title “Treasury of Truth” in 1993. His awards are numerous, publications are truly countless. In his small apartment cupboards are teeming with awards and thank you souvenirs, reflecting back to him his deep care and connection to the community.

Despite his achievements, he gave his time and committed to his work with a spirit of generosity and a sense of humility. He would welcome anyone with warmth and would never shy away from teaching his craft. The clarity with which he lived his purpose came to him from a very young age, illustrated in a story that he told often: the story of his class teacher, L.H. Jayasena asking a class of ten year olds what they wanted to be when they grew up and a young Edwin Ariyadasa declaring he wanted to be an editor and being laughed at by his classmates. In his retelling of the story, he reflects on the fact that the editor post as a career choice was not something many were familiar with at the time in the setting he lived in. He also reflected on how we never understood what drove his voracious appetite to read and his goal to become an editor. It remained a mystery to him.

My connection to Edwin Ariyadasa was deeply meaningful to me. Starting from the shared joy of sharing a birthday, our passion towards writing, spanning to his guidance on leading with compassion as opposed to perceived righteousness, are things that have stayed with me. In my re-telling of these stories, I also hope to create his presence that emanates joy, care, compassion and his unparalleled brilliance within these memories.

My first memory is an alms giving. I was too young to know the recognition Edwin Ariyadasa had at the time. At my aunt’s in Kandy, I remember a well dressed (he was known for his shirts and jackets) somewhat older gentleman coming into the living room and immediately commanding the room with his presence. The alms giving was for my grandfather (Edwin Ariyadasa’s older brother) to commemorate his passing. My grandfather always used to sing a song about the river Yamuna, a river in India that holds cultural and religious value to many. My grandfather liked the song so much and would belt out “Yamuna, Yamuna Shobhana Ganga” whenever he was happy or slightly buzzed. During this alms giving, which is my first clear memory of meeting Edwin Ariyadasa, two thing happened: first, he told me that we were born on the same day and so I am as old as he was; second, he told us all that whenever my grandfather used to sing the song about Yamuna he always told my grandfather, “I have crossed this Yamuna that Ayyandi (older brother) is always singing about.” A story that was oft repeated, always with deep affection. This was my first learning experience about our family’s attempts at humor reflected even among the most senior members. It was a testament to his deep care towards leaving a legacy of compassion even within the family. Towards his final days, in my conversation with Sudu Seeya, he told me that he considered it to be his duty to pay back the love he received from all his family. Edwin Ariyadasa was the youngest of six (three brothers and two sisters) siblings and was cared for deeply by all of them. This was the first moment that I witnessed his deep gratitude for the care he received which he believed was a great foundation for his success and something that he thought he needed to pay forward.

The second memory is when I was grown up, 19, about to leave Sri Lanka for academic pursuits and visiting him. In my years of growing up, Sudu Seeya and I had conversed about the passion for reading and writing. Our meetings were scattered because he lived in Colombo and I grew up in Kandy. However, our meetings mattered as ways to celebrate our common interests and for me to be inspired. So, as I went to his place to bid goodbye, pay respects before leaving he asked me about my passion for science and literature and told me the future is in combining these – not as separate pathways. This has had a huge impact on my career choices and my approach to science in general. In our later conversations, we would reflect on how science communication has become a buzzword and how his guidance shaped me. Yet, despite his best efforts in developing science communication in Sri Lanka, challenges lie ahead for our country and the world in communicating science to the public. It matters now more so than ever as we face global crises. Perhaps his advice to me when I was 19 of humanities and science not being two distinct different fields but an opportunity for interdisciplinary growth matters now more than ever to students, parents, politicians and to anyone who cares about humanity.

Third is during a time I was working on rights-based development and right to health in Sri Lanka. I was enraged at the human rights violations, the actors responsible, and he asked me to pause and reflect before writing things to the public. His advice was to understand that not everything might be as it seems, to learn that conviction and the force of righteousness may not always mean our actions are helpful or even that we are doing the right thing. He emphasized that empathetic viewpoints help more than we think, especially in conflicting spaces. I want to say, I agreed, went home and changed my ways but I did not. However, as I engage more and more in complex challenges, whether it is in global health or otherwise, I understand the importance and the interconnected value of building bridges than burning them. Perhaps a key factor that relates to community building against common challenges is to not let ideas of righteousness lead without empathy.

Fourth, towards the end of his days, I remember visiting him once in 2019 and then in 2020 as I continued to be away from Sri Lanka. In 2019, we had the conversation mentioned earlier, where he told me about his role as the oldest member of the family to payback the love that was given to him. He took this responsibility seriously. If you ever knew Edwin Ariyadasa, you would recall that he always treated you with warmth, listened to you intently, shared some of his knowledge on the topic and most of the time ended up recommending some readings if he felt you are so inclined. If not, he would tell a story often ending with a joke; if it is his home you are meeting him at, he would definitely offer you tea or coffee. The joy of his booming hello was contagious and you knew he would help you; a trait that was perhaps exploited. Though he remained ageless until the very end of days, signs of ageing were starting to show in 2019. We often talked about the books that he wanted. It was one of the things that I took pleasure in, bringing him books that he wanted but could not find locally. He was eager to read Barack Obama’s new book A Promised Land, but it was not out yet. In late 2020, I met a fragile but lucid Sudu Seeya ready for departure, and I brought up the topics of books just to distract him and carry our conversation forward. He said, “I do not have energy for books anymore and now I enjoy thinking about the happy memories of my childhood.” He had finally stopped reading and put his pen down. On January 22, 2021, he passed away.

At the funeral, a national affair, with speakers blasting at the cemetery of him telling the story of wanting to be an editor at a young age on repeat and with many dignitaries paying tribute, I wondered how many of these eminent guests would follow his example beyond speeches. Sri Lanka remains at a precarious stage. As a community we are increasingly pushing values of becoming technical experts without creating cultures of empathy and compassion. In 2022 we are still debating if art and writing are valuable in Sri Lanka. We are failing at leading with commitment to serve and with integrity. While we praise the genius of Edwin Ariyadasa, showcase his achievements, my hope is that we will also learn from his path and his values, which put compassion and care for the community above all else.