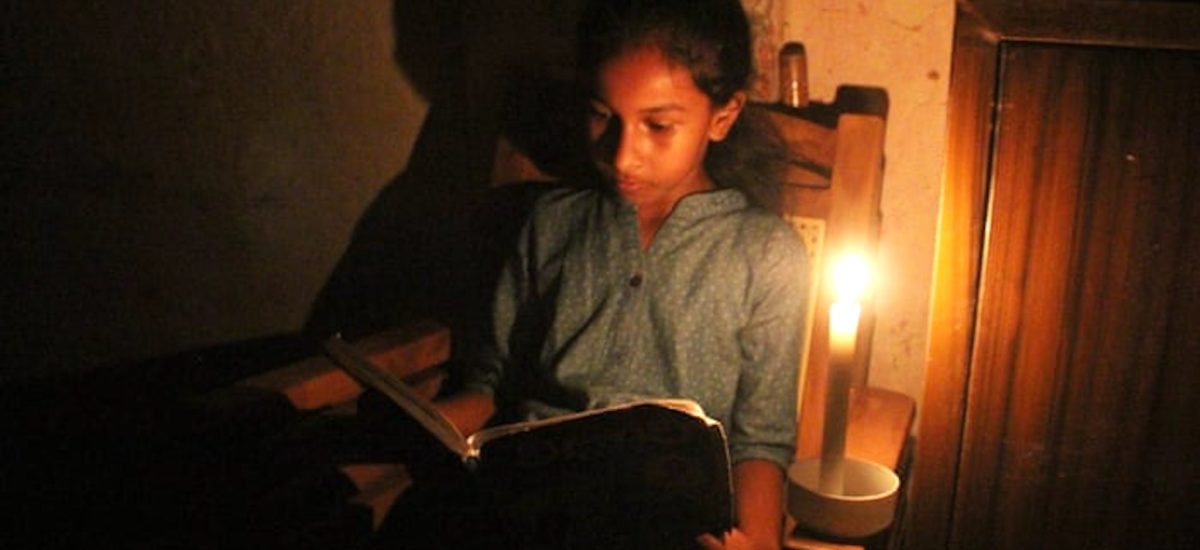

Photo courtesy of The Guardian

A nation was promised vistas of prosperity and splendor and about 6.9 million voters opted for it, subsequently providing a two third parliamentary majority to implement the vision. A little over two years later, the reality is experienced by everyone – shortages of everything from cooking gas to milk powder and foreign exchange to crude oil and the resulting power cuts.

There is little need to expound at length the economic, social and pain that the populace is experiencing. It is a daily experience that will speak the loudest at the ballot box when the government musters up the courage to face the polls, be they the delayed Local Government or Provincial Council elections. This is a government running scared of facing the electorate. Covid-19 is hardly an excuse; we had elections in August 2020 at the height of the first wave and after a long lockdown. We are since vaccinated, masked and learning to live life with a virus, dengue and a shortage of everything.

What is more useful is to study the colossal policy and political failures of the SLPP/Rajapaksa administration so that perhaps the government can learn from its mistakes and make a course correction and that a future SJB administration could avoid the blunders of this government’s current tenure.

Majoritarian ethno-religious nationalism has it limits

It is Samuel Johnson who in 1745 is credited with the saying “patriotism is the last refuge of the scoundrel”. Then, as now, what Johnson and other political theorists argued was that it is very easy to play identity politics or ethno-religious nationalism to mask self-interest and ignore sound public policies and prudent governance. Unfortunately for Sri Lanka, post war the administrations of 2010-2014 and 2019 to date have heightened divisiveness and polarization in society for political power. In the discourse on Sri Lanka’s national question, there is often the claim, not without merit, that the British colonial administration practiced “divide and rule” in Ceylon as well as in other colonies. In reality we don’t need to go that far back in history to see divide and rule politics in Sri Lanka. But what the elections of 2015 demonstrated and future elections will demonstrate is that there is a limit to economic pain and bad governance that a majority in society will tolerate notwithstanding the most strident and ardent ethno-religious nationalism. Lesson 1: Ardent ethno-religious nationalism is not a substitute for sound policy and prudent governance.

The military is not there to run the country

The Sri Lankan military is one of the best in the world and until scepticism set in about our domestic human rights enforcement and safeguards, widely desired for UN peacekeeping roles as one of the few militaries with actual combat experience. However, a military like any other state institution and structure has a role and purpose. To pervert that role and purpose is to do a disservice to society and also to weaken the institution concerned. The military’s latest mandate from this administration has become “green agriculture”. The government’s epic failure was denying to farmers and planters non-organic fertilizer overnight. One wonders how the light infantry or the heavy artillery is to be deployed effectively for organic farming. The government has become heavy on presidential taskforces, the latest one being headed by an ex-convict, that almost prompted the Justice Minister to throw in the towel. The governance of Sri Lanka’s democracy requires as President Ranasinghe Premadasa stated, “Consultation, compromise and consensus”; a process and skill that the governing party, the ruling family and the powerful generals and admirals running the country seemingly have in short supply, if at all. Democratic institutions of governance must be allowed to function freely, robustly and independently. That is not the case today. We do not need a Hitler; we need a Mandela. Lesson 2: The military is not an answer to every problem.

Policy not politics should drive governance decisions

At the heart of the current economic woes are two key political decisions of the administration and not a virus named Covid-19 and its mutations. The first and most negative decision the government took in December 2019 was to slash and roll back the tax increases that had been painfully introduced by the previous government. This in a country that has an extremely narrow tax base and a very low tax revenue to GDP ratio compared with peer nations. We are today going hat in hand to Bangladesh for foreign currency and swap arrangements. The failures of the government’s fiscal policy are not just on full display; its resultant monetary policy implications are now felt in the pain of everyday living as shortages of all imports essential to daily life from fuel, medicines and cooking gas to basic food items mount and continue with no end in sight.

The second policy blunder, effected last year, was to overnight ban non-organic fertilizer. The resulting decline in agricultural yields, farmer incomes and increase in food prices combine to create severe hardship to rural farmers and urban consumers. Both these decisions ignored the advice of economists, policy experts and community leaders. The administration promised technocracy driven sound policy but we have ended up with quite the opposite. A small elite, listening to an echo of its own words. Lesson 3: Rome was not built in a day. We do not need shock therapy that is all shock and no therapy.