Photo courtesy of Kumanan Kanapathippillai

“Sri Lanka has the world’s second-highest number of cases registered with the United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances. Since the 1980s, an estimated 60,000 to 100,000 people from all ethnic and religious communities have disappeared. Many victims are believed to have been abducted, tortured, and killed by government security forces, including units operating under the country’s current political and military leaders,” according to Human Rights Watch.

For many decades, families of the disappeared have been engaged in the seemingly hopeless task of finding out what happened to their relatives. Successive governments have promised much but delivered little. Those searching for the disappeared are shunted from pillar to post visiting military camps and police stations while giving testimonies at numerous commissions of inquiry and suffering humiliation and threats as they continue their search.

Former Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe dismissed the disappeared as being “probably dead” while President Gotabaya Rajapaksa said, “I can’t bring back the dead.”

International patience is wearing thin and several high ranking military officials, including Army Commander Shavendra Silva, have been subject to travel sanctions imposed by countries seeking to pressure the government to move in the direction of finding the truth, administering justice, providing reparations and ensuring non-recurrence – the four pillars of the transitional justice process.

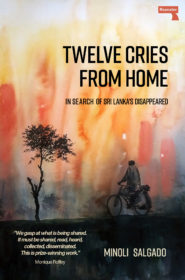

Often lost in the circles of accusations, counter accusations and denials are the voices of those who have suffered and are still suffering daily; their pain is continuous and unabating. In order to bring some of these stories to the forefront Minoli Salgado, Professor of International Writing at Manchester Metropolitan University, travelled throughout the country to collect the testimonies of 12 men and women for her book, Twelve Cries From Home In Search of Sri Lanka’s Disappeared.

Radhika Coomaraswamy, a former UN Under Secretary General, writes in the preface to the book, “On the one hand this book could be read as a chronicle of unbelonging and alienation, and on the other as a book of yearning, with the hope that the retelling of the shared history of suffering will lead to acknowledgement, recognition and healing.

“One thing is clear: while the book draws us deep into archetypal realities on the effects of political violence, its unflinching, searing focus on the experiences of civilian survivors from across the island marks an important contribution to our understanding of Sri Lanka’s long and brutal civil war.

Minoli answered questions from Groundviews on her experiences of writing the book, what she hopes it will achieve and how the country can move forward.

What motivated you to do this book?

Twelve Cries from Home emerges from my long-standing interest in trying to find an ethical response to writing about the Sri Lankan war and, more generally, in the writing of hidden histories and traumatic experiences. I have focused on this in my fiction and poetry and of course explored the issue academically but never engaged with writing true stories, directly related to me for the purpose of being retold. The experience was – and continues to be – a real learning curve.

Was it difficult to distance yourself and remain objective when listening to such harrowing stories?

I had no intention of distancing myself while listening; the aim throughout was to connect, to keep politics out as much as possible and to relate to things on the human level. It is politics that caused this war and the people I was speaking to were ordinary civilians who were trying to get by. The process of listening to them was emotionally draining – I was absorbing a lot – but the connections made were humbling and enriching. I feel deeply privileged to have been able to do this work, to have people trust me in the way they did.

What is the importance of telling these stories? Is anyone listening?

All the people who spoke to me really wanted their stories to reach a wider audience. They had all contributed to Truth Forums run by the National Peace Council and some had worked with the ICRC and had their stories included in Amnesty International reports. These spaces are quite contained and reach audiences that are relatively informed and predisposed to learn more. The book provides a new platform and is aimed at a general readership and I chose a direct prose style to suit this. People are listening. We just need more people to connect and to create a context where listening is made possible. Life stories are important vehicles for advancing human rights and building connections between peoples, and this is a book about linking up and building connections with people from across four regions of the island.

Did you find differences in how people reacted to loss in the north and south?

I address this difference in the book and found that it would be reductive to read things purely in terms of a North/South divide as so many victim-survivors were and are displaced. While there were certainly different degrees of trust in the people I met, what ultimately shaped responses were the personal qualities of the individuals I spoke to. Things like gender, age, educational background, occupation, cultural expectations relating to speaking to someone like me and even small things like the space the conversations took place in. I am conscious that if I spoke to them at another time and place – one woman, for example, was especially emotional as she had just lost her niece – or framed questions in a different way, a different interaction and telling would have taken place.

Did most people seek justice or did they feel the need to know the truth about happened?

The thing to remember when we speak about justice is that it is an unfinished endeavor, an ongoing process that is aspirational. Peter Goodrich has described it as ‘an always-failed attempt to actualize an ethical commitment and accounting of the past’. Most of the stories in Twelve Cries relate to historical violence, some of them go back thirty years, so most of the people are resigned to the fact that they will never find out the truth and recognize this unfinished, aspirational aspect of justice. Some were even perplexed by the idea of justice, as you describe it, as this notion was so far removed from their experience, and many resorted to a sense of cosmic order or karmic law to give moral meaning to events. This does not necessarily mean that they have come to terms with the things that happened or that they have dropped the idea of accountability or reparation – the stories reveal a whole gamut of emotions from anger and grief to calls for revenge – but that the needs of the present are overwhelming, and for this reason the talk of reparation kept coming up. What was striking, and was common to all the narratives, was the need to be recognized and for the legitimation of their experience – a call, you could say, for official acknowledgment and recognition of historical wrongs.

In Argentina women have been looking for their sons since 1977. Does this show that the matter will never fade away until addressed?

I believe so. Suppress something and it will always return to haunt you. This is true of individuals and of nations. The truth always comes out. It may not come out quickly or immediately, or come out whole or comprehensively but, bit by bit, it will come out.

In the Sri Lankan context finding truth and bringing perpetrators to justice seems an insurmountable problem. What do you feel is the way forward?

Every country has to find its own way of addressing historical wrongs; the important thing is to bring suppressed things to light in a way that supports victims and breaks the cycle of violence. We have a long history of regenerative violence and the civil war itself was so protracted that the need to break out of this cycle is great. We can only do so, though, if we address the needs of victims – all victims – and develop policies that break polarizing and exclusionary discourses and practices of identity so we treat each other as equal members of society. To do this, we need to find a balance between retributive justice and restorative justice, between marking accountability and building community. Story-telling and story-listening are crucial to this process as they serve to record wrongs while also creating the space for circuits of connection across cultural difference, establishing new modes of belonging to a community.

Do you think a truth commission is the way to go? Can it be a people’s truth commission as in Aceh?

Truth commissions have an important role to play as they work on including victims’ stories as well as those of perpetrators, undercutting totalizing narratives of the state and revealing the complexities underpinning historical violence. In the case of Sri Lanka’s long history of political violence, truth commissions and forums could be especially useful as they provide a space to legitimate victims of war – and thus fully citizen them – and acknowledge the fact that the boundaries of victimhood are not clear-cut, that those who are victims in one context can be perpetrators in another. The polyvocality of truth hearings keeps the complexity of political violence in full view. The hearings can also break the revenge cycle by building an imagined community, thus working towards a form of justice that is both restorative and transformational. The important thing is to keep it victim-centered, to begin from the ground up. Yet, as your reference to Aceh indicates, there are limits to what truth commissions can do and there is often a large gap between the objectives and results. The strengths and weaknesses of these commissions are linked; the fact that they are not judicial bodies means accountability can be marked only by name, and the very pliability and provisionality of a forum that accommodates and registers the complexity of political violence can muddy the waters. I see truth commissions as part of a larger process of rebuilding a society after war, an important by-product if you like of our ‘always-failed attempt’ at justice.

What do you hope to achieve by writing these stories?

The obvious aim is to get the stories out and to create a space for listening to ordinary Sri Lankan civilians who have been deeply traumatized by the war. Another entirely literary aim is to find an ethical form of writing trauma that marks the process of mediation so that my inevitable appropriation and retelling of another’s narrative is clear. And, last but not least, I hope that in bringing together the stories of civilian survivors from across the country I have generated a context for understanding that might allow us to connect and understand one another more.

How has doing the book changed you as a person?

Every book you write affects you in some way but this one has had the biggest effect. Before I wrote this book, I had tended to move in quite safe circles occupied by people like myself. The journey charted in this book changed all that, took me into experiences that I still find hard to comprehend. Some things have shattered into clarity. I see the country quite differently now. With a deeper tenderness.