Photos courtesy of Paradise Road

When Ajantha Ranaweera was ten years old, his brother who was in the army went missing in action. Several years later, he was declared dead. There were no remains. On that day in 1999, he and his family began the difficult journey of coming to terms with what had happened.

That journey from despair to bliss is depicted through the paintings in Ajantha’s first solo exhibition at the Paradise Road Gallery Cafe. A chartered architect, designer and artist, Ajantha hopes that his work will highlight the trauma caused by all disappearances and convey the tragedy suffered by everyone who is touched by war.

“Whatever the reasons were for the war, in the end, we all are victims. There are no victors in war; all who disappeared or died are individuals irrespective of which side they belonged to. If we are to look beyond war towards reconciliation and peace, we have to move forward as individuals and as a society through awareness and education. This is to learn from the past in order never to repeat violence,” Ajantha said.

“For reconciliation to happen the loved ones of missing persons need closure. Within this framework, I know that many people are struggling for justice and accountability. However, I see reconciliation as part of a much larger process. For me this process starts with everyday conversations about the victims as individuals not as a collective. Through such conversations we begin to understand that those left behind are not alone on this journey. One needs to have such conversations with one’s own self and then from there with others with mutual respect and from a safe platform. For me these platforms lie within my own mind, art and galleries.

“I hope my art work will contribute to the broader discourse in society on the topic of disappearance which is largely neglected, denied and supressed. In my exposure to architecture, our history of violence is not discussed as relevant to education either in a narrow sense or in a wider framework engaging violence, history, archaeology and art,” he added.

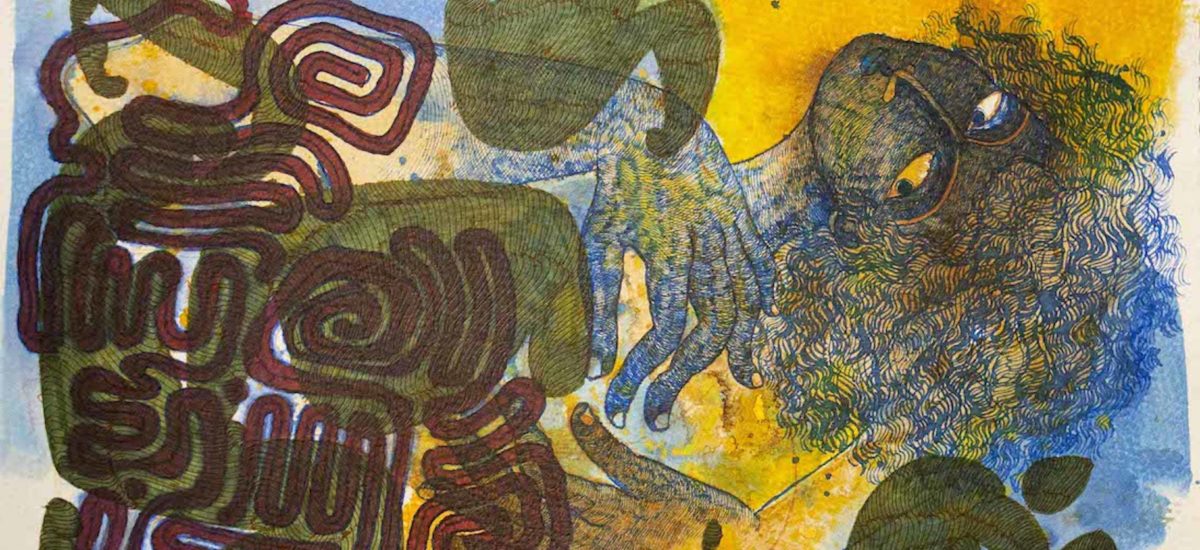

“The works presented in the exhibition are to be taken as a collective; different parts of a much larger idea. Also the works can be looked at in layers, first as a pretty drawing. The more layers you unfold, broader the discussion becomes. I imagine the disappeared to be in a place of peace and harmlessness. A type of safe house, which is depicted as a stylised Sri Lankan garden. A garden of paradise,” he explained.

Are you and your family looking for the truth about what happened to your brother or do you want accountability and justice as well?

We have no remains, only a location where it happened. For my family, even if we get accountability and justice, it won’t bring my brother back. That is why I focus on looking beyond violence to find a different way of being in peace within myself. In my art work, which is a social product, I feel I have a duty to contribute to the larger discourses on disappearance.

Is the title meant to be ironic or is does it mean that the disappeared are now in paradise?

It’s not meant to be ironic but I do see the ironic aspect of it as well. From the point of view of a person who has lost someone, it is a kind gesture to help them imagine their loved one in paradise out of harm’s way, in a safe house where the violence of man cannot reach them. Moving forward, it fascinates me to see how people relate to this title. Their varying interpretations further encourage people to look at disappearances from multiple avenues, leading to a much broader discussion which can advance awareness.

What is the significance of the maze?

One aspect is to show the wondering mind, dazed and confused. The maze is also a reflection on ancient Sri Lankan garden design traditions and their intimate connection with sophisticated trans-basin water management systems. I think that our indigenous conceptualisation of garden design is inseparable from the design and construction of the huge wevas and sluices and the smaller subtle designed and manmade ecosystems of the cascades, water channels and paddy fields that comprise much of rural Sri Lanka. Strands of historical design knowledge from around 600 BCE to date converge in the paradise depicted by a metaphysical Sri Lankan garden.

Why did you choose the blues and browns?

Through inspirations from my travels and reading about murals, fabrics, ceramics, architecture and most importantly reimagining indigenous gardens. I’m more cosmopolitan when it comes to colour and combinations, inspired equally by east and west but I always will have a special place for our own. I have learnt from looking at Geoffrey Bawa’s approaches to design knowledge.

Are the distorted bodies to show torture?

The bodies for me are stylized in the manner of the figures seen in the paintings at Sigiriya, Tivanka, Dambulla or Kandy. It’s partly the result of my explorations on the discourse of decolonizing knowledge. Jagath Weerasinghe alludes to the nationalist phase and the appearance of the nude male body as a motif in art in the 90s as having a symbolic connection to the people who disappeared or were tortured and killed in the violence that happened in the South from the 70s. I do not want to literally show brutality but just to symbolically relate to it.

Do you think your art, by drawing attention to the long standing issue of disappearances, can make a difference in bringing justice to victims?

I see that disappearances are an important part of a much larger process generating discussion and awareness about violence through education. I focus on a more holistic approach towards reconciliation, inspiring change within us, teaching us to reflect so that we may never repeat the brutality of the recent past. Violence cannot resolve disputes.