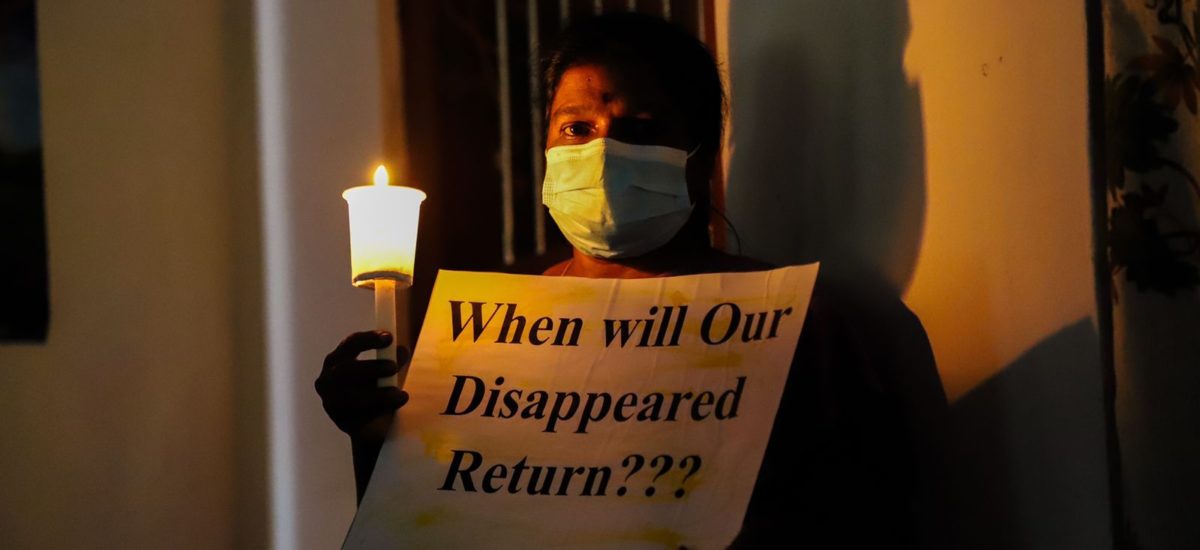

Photo courtesy of Kumanan Kanapathippillai

As the United Nations Human Rights Council (HRC) meets for its 48th session, the dire situation in Sri Lanka is under international scrutiny. Amidst ongoing concerns, work has begun on holding the Sri Lankan state accountable, according to United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet on 13 September. The UN Core Group on Sri Lanka consisting of the United Kingdom, Canada, Malawi, Germany, North Macedonia and Montenegro also flagged grave and persisting problems, while Foreign Minister G.L. Peiris was adamant in refusing to accept government accountability for its treatment of those in its power. The credibility of the regime, at home and abroad, is now extremely shaky.

Mounting evidence of violations

In March 2021, the HRC passed a resolution on promoting reconciliation, accountability and human rights in Sri Lanka, despite government opposition. While the government was given time to reconsider, this included a call for “the Office of the High Commissioner to enhance its monitoring and reporting on the situation of human rights in Sri Lanka, including on progress in reconciliation and accountability, and to present an oral update to the Human Rights Council at its 48th session, and a written update at its 49th session and a comprehensive report that includes further options for advancing accountability at its 51st session, both to be discussed in the context of an interactive dialogue.” Implicit in this was the possibility of firmer action to protect Sri Lankans if there was no progress.

International human rights agreements and codes of practice cover a range of rights from the political to the social, cultural and economic. On all these counts, the past few months have brought further serious concerns to the fore. It is not only minorities, trade unionists and human rights activists who have been gravely affected: hardship and insecurity have impacted many outside the favoured circles close to the Rajapaksa family. Meanwhile calls continued for redress for past injustices and answers for the families who cannot yet mourn their loved ones properly because they have been denied the truth.

In the run up to the 48th regular session being held from 13 September to 8 October 2021, some of this evidence found its way into reports highlighted by international organisations. There were also ongoing pleas for justice from within the country despite the risks to human rights defenders there.

Human Rights Watch urged UN member countries to “express their alarm about the ongoing abuses by the government of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa and the weakening of independent governmental institutions, civilian governance, and the rule of law. These countries should demonstrate their willingness to press the Sri Lankan government to meet its international human rights obligations” and take firm action.

The International Truth and Justice Project released a disturbing report on the ongoing abduction, torture and rape of young Tamils by the police and army, describing the ordeal of 15 victims and the ongoing effects on them. Many had been involved in peaceful protests. It is not certain how many youth are still held in horrific conditions.

Within the UN, too, work was taking place on Sri Lanka and other countries where there was cause for concern. In preparation for the HRC, the Special Rapporteur on the promotion of truth, justice, reparation and guarantees of non-recurrence, Fabián Salvioli, produced a hard-hitting “Follow-up on the visits to Burundi, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and Sri Lanka”, which spelled out the recommendations of his predecessor and the track record and many failures of the governments concerned. As has been pointed out, it is not only smaller countries or those in the Global South that are pulled up when they fail to respect and safeguard people’s safety, dignity and wider rights.

Salvioli, an Argentinian human rights lawyer and professor, described the various ways in which the hopes of positive moves had been dashed and indeed matters had become worse. Opportunities for national healing had been squandered. “The Special Rapporteur regrets that no truth commission has been established to date. Such a mechanism would be of considerable value in helping Sri Lanka to understand the root causes of the conflict and open a common public platform for all communities to share their lived experience.”

Instead, “Over the past 18 months, the human rights situation in Sri Lanka has seen a marked deterioration that is not conducive to advancing the country’s transitional justice process and may in fact threaten it. The Special Rapporteur deeply regrets the insufficient implementation of the recommendations made by his predecessor and the blatant regression in the areas of accountability, memorialization and guarantees of non-recurrence and the insufficient progress made regarding truth-seeking. He urges the Government to swiftly revert this trend in order to comply with its international obligations.”

Militarisation and the lack of accountability

In her oral update on the human rights situation in Sri Lanka, Michelle Bachelet outlined how “The current social, economic and governance challenges faced by Sri Lanka indicate the corrosive impact that militarisation and the lack of accountability continue to have on fundamental rights, civic space, democratic institutions, social cohesion and sustainable development.” She mentioned the state of emergency declared on 30 August, “with the stated aim of ensuring food security and price controls, amid deepening recession. The emergency regulations are very broad and may further expand the role of the military in civilian functions.”

Repression was not being removed but rather widened. “Surveillance, intimidation and judicial harassment of human rights defenders, journalists and families of the disappeared has not only continued, but has broadened to a wider spectrum of students, academics, medical professionals and religious leaders critical of government policies. Several peaceful protests and commemorations have been met with excessive use of force and the arrest or detention of demonstrators in quarantine centres.”

She drew attention to the dropping of charges against a former Navy commander suspected of involvement in several disappearances, unanswered questions about the 2019 Easter Sunday bombings, deaths in police custody and “new ‘de-radicalization’ regulations…that permit arbitrary administrative detention of individuals for up to two years without trial”. The Prevention of Terrorism Act was being used to hold people such as lawyer Hejaaz Hizbullah and teacher and poet Ahnaf Jazeem for prolonged periods without being brought to trial. She raised concerns about the appointment process to, and effectiveness of the national Human Rights Commission.

“Against this backdrop,” she stated, “my Office’s work to implement the accountability-related aspects of Resolution 46/1 has begun, pending recruitment of a start-up team. We have developed an information and evidence repository with nearly 120,000 individual items already held by the UN, and we will initiate as much information-gathering as possible this year. I urge Member States to ensure the budget process provides the necessary support so that my Office can fully implement this work.

“I encourage Council members to continue paying close attention to developments in Sri Lanka, and to seek credible progress in advancing reconciliation, accountability and human rights.”

Responding to the High Commissioner’s concerns

The government’s dismissal of the extensive evidence of its failings was perhaps predictable, given its past record. But the problems will not go away.

The Core Group on Sri Lanka reiterated many of the concerns and urged that the Office of the High Commissioner be provided with the resources it needed to take forward the earlier resolution.

While the pandemic has undoubtedly presented challenges in Sri Lanka as in many other countries, the government’s approach has left people even more exposed, as it gives priority to its own power seeking over saving lives. Other failings too may lead increasing numbers to suspect that the government cares little about ordinary people from any ethnic or religious community, except at election time. Its attempts to silence critics and peaceful protestors, however brutal, cannot wholly stamp out dissent. The regime may hope that influential foreign partners and public relations skills may help it to keep fending off criticism at home and abroad. Yet, especially if the crisis worsens, it is unclear how effective this will be.

Meanwhile, the state’s refusal to guarantee human rights for all adds to the suffering of people already facing fear, loss and insecurity. If those affected in varying ways can support one another as well as making links with those internationally who care about the plight of Sri Lankans, progress towards justice might be achieved.