Photo courtesy of Rohan Wijesinha

“Those who cannot learn from history are doomed to repeat it.” George Santayana

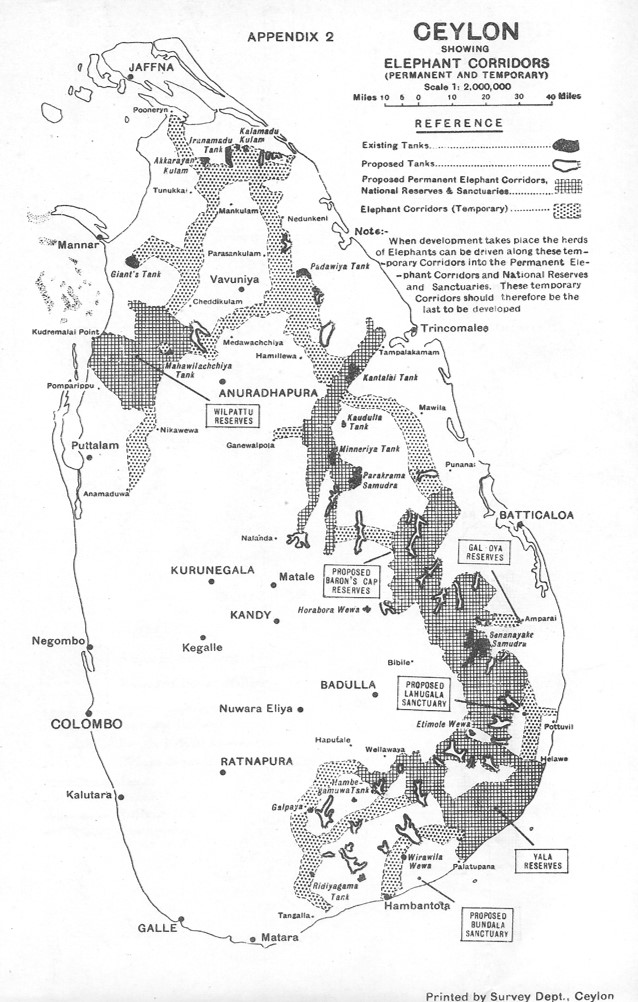

In 1949, a year after Sri Lanka gained independence, a Committee on the Preservation of Wildlife (Sessional paper XIX – 1949) recommended that when development takes place, elephants living in the proposed areas be driven into national reserves and sanctuaries and that temporary corridors be set between these protected areas for the purpose of these drives. Their well-meaning recommendations were based on the knowledge that they had at the time, primarily anecdotal evidence, with little or no comprehensive research available on elephant distribution, ranging patterns and behaviour. At that time, the human population of the country was less than eight million and the supposed wild elephant population was about 1,500. We now know that this latter figure was far from accurate and that that the true figure probably exceeded 10,000.

A census conducted by the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC) in 2011 concluded that Sri Lanka had about 6,000 wild elephants. Comprehensive research conducted over the past quarter of a century by the Centre for Conservation Research (CCR) and others has shown that these elephants live on 60 per cent of the land mass of Sri Lanka, over 40 per cent on which they co-exist with humans. This research also shows that elephants do not adhere to arbitrary administrative boundaries drawn on a map but range between areas of seasonal food and water; a behaviour of many centuries, if not thousands, of years of practice and which the local human communities understood and adapted to.

Most importantly, what we now know is that the DWC Protected Areas (PAs) are at or near their carrying capacity of elephants and if more wild elephants are driven in and enclosed within them, they will soon starve to death as they deplete the area of the large amounts of fodder they each need to survive for a day. In addition, research data shows that when the carrying capacity is exceeded, even the elephants that are resident in the PA are deprived of the fodder they need and starve. In any case, denied access to other populations of elephants they would be forced to inter-breed, thereby facing inevitable extinction.

Beating the same drum

The DWC was also established in 1949. Officers were once promoted to positions of responsibility based on their experience and longevity of service within the institution. Today, and quite rightly, experience alone is insufficient and those with ambition to reach the top must also have suitable academic qualification; science to complement familiarity.

As such, it is astonishing that the DWC continues to beat this same drum of pushing elephants into restricted areas and then constructing electric fences around them, mostly on political demand, while ignoring the lessons of history, and of science. The DWC’s own National Policy for the Management of the Wild Elephant in Sri Lanka (2006) states, “It is imperative that lands other than PAs under the DWC, that could support elephants be integrated into elephant conservation and management plans.” Despite this, the DWC continues to have plans for driving elephants into DWC PAs. For the past 72 years this policy has consistently failed. There has been no learning.

Putting policy into practice

In 2017, the DWC updated its 2006 policy with the assistance of a multitude of stakeholders – researchers, scientists, former DWC Field Officers, conservation groups and others. One of the first actions was to take out the clause on large scale elephant drives, mostly based on the bitter experience of the last drive from the West Bank of the Walawe into the Lunugamvehera National Park when the bulk of elephants driven in were females, juveniles and calves who do not cause Human–Elephant Conflict (HEC). The majority of males, who do, were left outside. According to a survey undertaken by CCR, 71 per cent of the people in the development area felt that HEC was the same or worse after the elephant drive. Many of the herds who were driven into the national park and fenced in there died of starvation. Therefore this elephant drive, which cost the public Rs. 62 million, did nothing to solve HEC in the area and was significantly harmful to elephants. So what was achieved?

Apart from the clause on elephant drives, much of the rest of the policy was based on scientific observation and had it been implemented, today’s carnage could have been avoided. Included was the establishment of Managed Elephant Reserves (MERs) that has now been promised for the Hambantota District, ironically, due to the determined lobbying of the local farmer communities rather than the DWC; an action that still continues as despite the Cabinet passing the creation of this reserve, its implementation continues to be thwarted by politicians, self-interest and the apathy of the Government institutions involved. This is the case with the 2006 policy too. Despite being passed by Cabinet, it was never implemented in full, with the DWC just picking and choosing aspects of it that would not cause too much resistance, especially from their political masters.

An action plan for progress

In 2020 President Gotabaya Rajapaksa appointed a committee to propose a National Action Plan for Human-Elephant Conflict Mitigation. Sri Lanka has the unenviable status of being the country with the highest rate of HEC in the world. This committee not only comprised of representatives of the DWC but also all of the leading stakeholders, inclusive of District Secretaries in whose areas HEC is taking place. The committee was chaired by Dr. Prithiviraj Fernando who is, perhaps, the most experienced researcher on HEC mitigation and elephant conservation among the 13 Asian Elephant Range States. His expertise on elephant conservation and HEC mitigation is sought throughout the region.

The report of the committee was handed over to the President on December 17, 2020. It is understood that the action plan is based on the revised national policy as passed by Cabinet and is grounded in science. We cannot be certain of this as the plan has not been made public and sits on some secretarial shelf while humans and elephants continue to die and the DWC continues doing what it has been doing for the last 70 years, with no success.

The stark reality

In 2019, Sri Lanka reached a sad place – the highest incidence of HEC ever recorded of 409 elephants and 121 human deaths. Due to restriction in human movement caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, there was a drop in number in 2020 but so far this year, 117 elephants have been killed in 119 days, many in the most horrible of ways – electrocution when farmers attach a connection from the main electricity grid to their fences; by the use of hakka patas, when explosives are hidden in food and explode when bitten into, blowing away the mouth parts and jaws of the elephants who die lingering deaths from blood loss and starvation; and from gunshots whose festering wounds take days or weeks to bring about the release of death. Official figures show that 2,806 elephants were killed between 2010 and 2020, which is almost 50 per cent of the total population counted in 2011. At this rate of attrition, it is very apparent that the wild elephant in Sri Lanka is on the brink of complete extermination.

Uncertainty as to the real number of elephants remaining in the wild makes it difficult to ascertain whether the remaining numbers are sustainable or whether they have reached a figure below that which is reversible for future survival. Their doom may already be determined. As such, it is difficult to comprehend when some politicians state that Sri Lanka has too many elephants and some of those that are left should be taken into captivity. Based on what science?

Sri Lanka needs wild elephants

Sri Lanka needs development, of that there is no doubt, but it must be planned and not at the whim of political ego and expediency to fulfill voting ambitions for the moment while leaving a legacy of environmental and economic ruin for the future. Apart from being a keystone species, the elephant is a creature that defines its ecosystem and without which that system would be dramatically changed or cease to exist altogether; elephants, and all other wildlife, are a source of economic wealth to this country. Prior to the pandemic, thousands of foreign visitors came to Sri Lanka to enjoy its tropical environment and pristine wilderness. Over 38 per cent of all visitors to this country went on safari to a national park or sanctuary. They went there to see wild animals in their natural surroundings, healthy and free. The “gathering” of elephants at Minneriya and Kaudulla has worldwide renown and Sri Lanka’s tourism advertising is prominently led by pictures of its natural wonders.

Elephants also contribute to the economy of local communities. The hundreds of safari jeep drivers, hotel owners and workers in these hotels that surround the Minneriya, Kaudulla, Uda Walawe, Wilpattu and Yala National Parks give evidence of this. In addition, with innovative thinking, other populations who live with wild animals as neighbours can earn an income from eco-tourism, thereby subsidising the paltry amounts they make from slaving for months in their cultivations. This will require a partnership between the Government, private enterprise and local communities but will result in strengthening the conservation of these protected areas as they become of increased economic worth to the local people. This is already practiced in a few places in Sri Lanka.

Saving lives

It must not be forgotten that between 2010 and 2020, over 800 humans lost their lives as well. These were fathers, mothers, sons and daughters, each a valuable life, the number of which could have been reduced by implementation of the updated national policy, for within its proposed actions, the protection of people is paramount.

Currently, there are approximately 4,500 kms of electric fencing in Sri Lanka that is placed, quite obviously, in the wrong place with about 65 per cent ridiculously separating Forest Department PAs from DWC PAs, with HEC increasing year on year. Astonishingly, the State Ministry responsible for HEC is considering spending a further Rs. 3 billion in erecting another 1,500 kms of electric fencing. Does this make fiscal sense, especially on a strategy that has failed so abjectly, for 72 years? At this time of economic stress? At a recent meeting the Chair of the Committee on Public Accounts (COPA) asked the Secretary to the Ministry if he could guarantee that this additional fencing would address the problem. He could not give this assurance as he stated that they “…did not know how elephants would behave”.

Yet, there are those who do; those who assisted in the upgrade of the national policy and who helped in preparing the National Action Plan for the President. Electric fences, for the present, are the best way of keeping elephants from an area but they need to be erected in the right place. As the priority should be to protect human life, fences should be erected around villages and village cultivations. This will not only protect human lives but will also permit elephants to wander on their traditional ranges without harm to man or beast. The fences around cultivations are designed to be seasonal so that they may be removed during fallow times. This, in turn, encourages elephants and other wild animals to browse on the remaining stubble, opening an opportunity for the farmer to profit from eco-tourism.

CCR has piloted this method in over 30 villages in the North West and North Central Provinces and it has proven to be 100 per cent successful. This is because the local villager and farmer associations have ownership of the fences; they erect them, manage their maintenance and ensure that it is done. In addition, each farmer pays a nominal fee towards its upkeep and, therefore, has a financial investment in ensuring its success. This also takes away the burden of electric fence maintenance from the public purse.

Look to the future

What the Committee on the Preservation of Wildlife did get right in 1949 is that there must be connectivity between PAs. They are vital for the health, not just of elephants, but of all large mammals, to ensure the interchange of gene populations and to prevent them having to intrude on human habitation and cultivation. These, however, must be based on science and on a landscape basis, dependent on the movement of species. The long narrow corridors originally envisaged are of no use to wild animals who, apart from being unable to read maps, stick to centuries old inherited learnings in moving from one place to another in search of food and water while mixing with other populations of their kind along the way. These studies will also show areas that are not used by wild animals that can then be released for development – planned development.

As it has quite rightly been claimed, Sri Lanka is greatly dependent on agriculture for the subsistence of its people but clearing forests is an insane way to try and achieve it, especially as the existing farming practices are inefficient and low in productivity. Forests are vital for rainfall and the preservation of water catchment areas. Their destruction will only result in less water and harsher conditions for agriculture; farmers who already lie at the bottom of the income table despite the important function they perform will be further entrapped in poverty.

Cutting forests as is currently being practiced illegally and under the Cabinet approved policy to clear Other State Forests will only result in environmental degradation, agricultural disaster and an increase in HEC.

What is left for tomorrow?

Sri Lanka is at a crucial point in its history when decisions made today will impact generations to come as at no other time since independence. This is because everything is at critical levels, exacerbated by a pandemic, and the wrong decision can result in irreversible, damaging consequences for decades to come. The pandemic has taught us that we are inconsequential when it comes to nature. Mess with it and it will bite back, taking millions of us away, for it does not need us for its existence. If we destroy our wildlife and forests and oceans, then it is only us humans who will suffer, even within the lifetimes of the elders who now have power to determine what the future might be.

In terms of culture and justice and humanity, future generations will hold us responsible if their inheritance is to be thirst, hunger and unbreathable air. The names of those whose policies made it possible will be cursed forever, as well as those who stayed silent and let it happen.

“Save the elephants, and then you save the forest – and then you save yourself.” Mark Shand