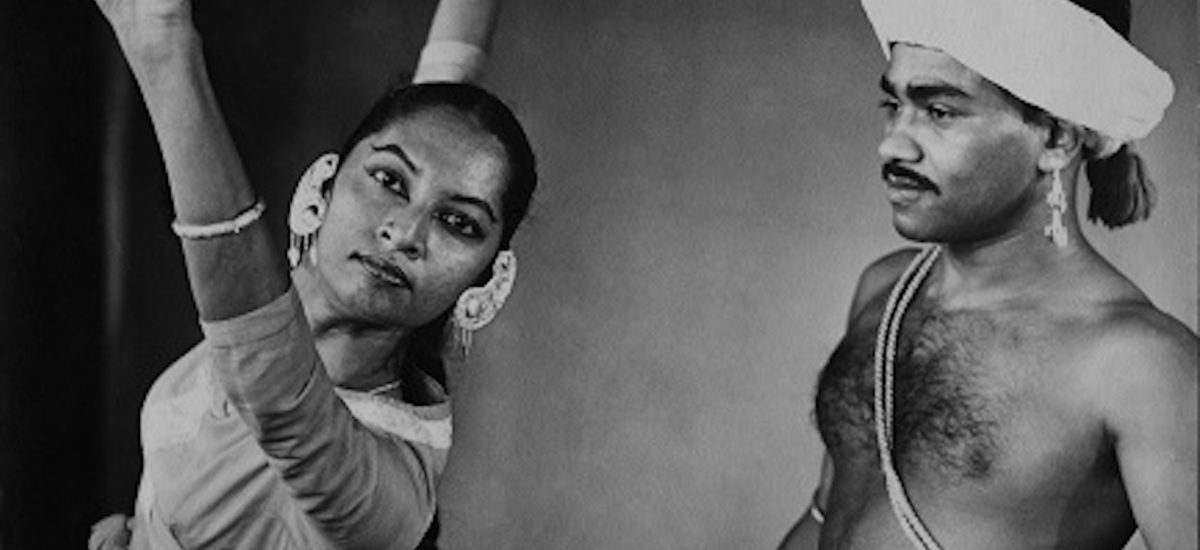

Photo courtesy of CVDF Archives

Histories of the tri-traditional dances of Sri Lanka – Kandyan, Low Country and Sabaragamuwa – generally highlight a handful of pioneering women, point out their significance as the first female dancers on stage and summarize their life stories. In these narratives their contribution is presented as creating a space for female dancers on stage. Yet, these female pioneers emerged on stage at a critical point in the journey of the tri-traditional dances from ritual space to stage. Temporally this overlaps with the early efforts of their male counterparts, both the ritual masters, the gurunnanses and stage dancers who were attempting to break in audiences. Rarely do these popular histories seek to account for the multiple roles these female pioneers served beyond carving out a place for women on stage to transforming the dance on the proscenium as performers, teachers, choreographers, troupe leaders, producers, costume designers, among others.

In this context, Vajira’s life story provides a useful prism to understand the development and contribution of the female dancer beyond that of a performer and teacher to a co-conceiver who pushed the boundaries of the tri-traditional dances on stage. Although the female dancer had historical antecedents (recorded in historical texts, literature and on rock and wood carvings) and was found in specific contexts in the pre-independence era, Kandyan dance, at least in its ritual form had no formal place for her. Vajira was preceded by individual female dancers such as Miriam de Saram and Chandralekha who broke new ground in the early 1940s encouraging a younger set of female dancers. Although Vajira had performed on stage before, including in largely in group scenes in the mid-1940s, her official debut was as the deer from the short sequence from the Ramayana in the Pageant of Lanka, held to celebrate the island’s independence in February 1948.

Embodying Lasya

Vajira is probably the first professional female dancer specializing in Kandyan dance. Dance for her was a full-time vocation, not an amateur interest. She came to dance reluctantly. As a child she tried to skip the classes at her home in Kalutara taught by a striking young dancer, Chitrasena who had making a name for himself. Encouraged by her mother she followed a series of dance classes in Kandyan and ‘oriental’ dance (a form of dance fusion sweeping across the Indian subcontinent and beyond) under various teachers. In 1946 she decided to join the Chitrasena Kalayathanaya as a full-time student. She became a member of the troupe and within two years became a soloist.

Performing on stages in Sri Lanka and cultural capitals across the world, including Moscow, Berlin, New Delhi, London and Sydney, Vajira was viewed as the epitome of the female performance and was referred to as the ‘prima ballerina of Kandyan dance’. In the media she was described as embodying the lasya (loosely translated as feminine) form of the dance, whereas Kandyan is seen to be a more thandava (masculine) form. Although Sri Lankan reviewers often highlighted her grace, they did not always capture the underlying strength and weight that she brought to the dance and her efforts to challenge her male counterparts on stage, to match their steps and leaps.

In a similar vein, the epithet highlights the recognition she garnered over five decades of performance, but speaks to only one of many contributions she made to the dance. It is only handful of short articles by commentators such as Ernest Macintyre, Karan Breckenridge and Samson Abeyagunawardena that draw attention to the breadth of her contribution. And only one or two, such as Sunila Abeysekera highlighted the personal challenges she faced and strength of personality to defy social conventions. In addition to her multiple dance roles, she was also a mother. She was determined to continue performing and touring despite the physical challenges of motherhood; barely three months after delivering her son she was part of a dance troupe performing in the USSR in 1957.

Vajira also served as teacher to successive generations of dancers and at 89 years of age would probably be conducting classes if not for the COVID-19 pandemic. Beyond teaching sections of the traditional repertoire as taught to her by her teachers Chitrasena, and Lapaya Gurunnanse (who was also Chitrasena’s guru), she developed her own pedagogy. Drawing from her limited exposure to other dance traditions including classical ballet during tours to Eastern Europe, the West and Australia or modern dance when artists such as Martha Graham visited the island in 1956, Vajira developed a series of exercises to break down Kandyan dance movements that could be used to train dancers.

These exercises made the processes of teaching and learning much easier and ensured greater clarity and consistency in lines and stances. In doing so she also expanded the range of movement, for instance adding floor to kneeling and standing exercises, whereas the ritual form has no movement where the dancer lies at floor level. While establishing herself as a principal dancer in the Chitrasena Dance Company by the late 1950s, she began exploring choreography. This included re-setting or creating new traditional items, collaborating with master drummer and composer, Piyasara Silpathipathi, and experimenting with the novel form of dance theatre, the mudra natya or Sinhala ballet. As a female dancer regularly performing on stages across the country and later internationally she served as a role model for young women passionate about taking up dancing as a vocation.

Children’s Mudra Natya

In this piece I will examine an area that has been rarely highlighted in articles on Vajira’s contribution to dance, her role in creating and conceiving children’s mudra natya or ballets. The term ‘children’s ballet’ may conjure up an image of a year-end pantomime for students to demonstrate their skills to relatives and friends, where the focus is less on artistry and more on demonstration and participation. Although Vajira’s productions employed simple story lines, they were often grand productions with large casts, that used original music scores and had fantastical sets. Vajira’s productions did not seek to compromise on originality nor artistry even while it provided space for children of different ages to perform.

It is remarkable that barely a decade after Chitrasena’s attempts at devising mudra natya, Vajira took on the challenge of exploring the medium for child performers in the early 1950s. Mudra natya emerged around the 1930s and 1940s marking a transition from dance dramas, as the former used dance as the primary narrative tool while the latter used a range of media such as song, spoken word and dance. She replicated Chitrasena’s approach of using Kandyan dancing as the framework for the choreography without being bound by it. In her experimentation with form, while drawing from Kandyan dancing positions and steps, she integrated natural movement and mime. She may have also been inspired by performances of children in dance dramas and western classical ballets.

Vajira claims that she began producing children’s ballets because she was inspired by the talent of her students at the Kalayathanaya. Seeing, teaching and working with talented dancers she felt she owed it to them to create pieces to showcase their talent. This seemed to be her ethos for choreography in general. The children’s ballets typically involved group scenes with different sets of children dancing in formation and solos for the more advanced and skilled (generally older teenage) dancers, with a heavy emphasis on expression and natural movement. Working with children from a broad age range, 6 to 14 she invested significant time to develop their differing capacities. These productions provided some of these kids, like Upeka (who is Vajira’s daughter) and Khema who would go on to become the next generation of female soloists, an opportunity to perform and gain stage exposure.

Her first ballet was also inspired by the musicians who at the time practiced and lived in the Colpetty school where she taught and which also served as her home with her husband and their three children, Upeka, Anjalika and Anudatta. Kumudini was Vajira’s first production, presented in 1951, titled after the song by Ananda Samarakoon and the music for the ballet was composed by Amaradeva. It is an allegorical story on impermanence told from the perspective of a flower that blooms and is eventually trampled.

Kumudini marked an important turning point: “When I started to experiment with creative dance, Chitra[sena] did not try to stop me. With 15-minute ballets I got more experience to do larger stories. I improved my experiences in creating movement and telling stories through dance.” She would go on to create 11 children’s mudra natya. Due to the relatively short duration of these ballets, they were presented alongside other items by the ensemble, so as to provide a full evening’s programme. When her fourth production, Vanaja showed in 1958, the latter half of the programme was a dance exposition of the Kalayathanaya’s approach to teaching dance to children.

Virtuoso Collaborators

The list of collaborators involved in the children’s ballets over the years includes an impressive set of figures in the Sinhala cultural world, attesting to the originality and quality of these productions. The scores for the ballets, for instance were composed by some of the leading musicians at the time including Ananda Samarakoon, Amaradeva, Somadasa Elvitigala and Victor Perera. Nil Yakka, included the song performed by Nanda Malini. As with the ensemble’s other performances, in the initial years the children’s ballets included an orchestra. During the 1950s musicians such as Shelton Premaratne, D.M. Pattiarachi, M.K. Rocksamy, Shelton Perera and G.W. Jayantha provided the live music before the Company shifted to recorded music. These productions provided a space for musical experimentation such as a chorus of four live performers accompanied by an orchestra in Ran Kikilli (1965), for which Lionel Algama set the music while Piyasiri Wijeratne composed the lyrics. These ballets included evocative sets and costumes, initially the work of the famous artist and designer Somabandu. His son Ravibandu, who is a well renowned drummer and dancer took on this role for the productions, Anaberaya (1976) and Hapanna (1979).

In order to devise the plots Vajira looked to multiple sources of inspiration and often found material in children’s literature and folk stories from Sri Lanka and elsewhere. In 1968 Vajira collaborated with the acclaimed local children’s author Sybil Wettasinghe to develop Nil Yakka (1968). Hapanna was inspired by the children’s book Swimmy by Leo Lionni which was first published in 1963. It is a fable on the benefits of team work and community told through a lonely fish who joins a shoal and convinces them to scare off a predatory shark.

Although the children’s ballet were Vajira’s domain, Chitrasena played a critical role in helping to provide the theatrical elements. She pointed out that “when I produced shows he would put finishing touches at the end.” These “touches” included vital elements such as sets, lighting, fund raising and advertising. Senior dancers also played a crucial role in supporting Vajira. Over time Anjalika, Vajira’s daughter took over the children’s ballets (Kumbi Kathawa in 2007) and the many productions for the Punchi Paada age group (4-7) including The Very Hungry Caterpillar, Kale Kolama and Thomas meets Udata Rata Manike, Ruhunu Kumari and Yaal Devi.

The children’s ballets offered Vajira the space to develop her creative skills and expand her repertoire. By the 1960s she was able to apply her choreographic skills to devise sequences in Chitrasena’s mudra natya starting with the swan sequences in Nala Damayanthi in 1963, where she also played one of the principal roles. In 1968 Vajira created a short mudra natya for her older teenagers, Gini Hora. The spark for this ballet lay in Vajira’s evening chore of sweeping the garden of the Colpetty home after which she would set alight the leaf litter. Watching the leaves recoil in the heat and catch aflame inspired her to create a short ballet about a set of thieves who try to steal a fire and then are cursed, turning them to birds.

A review of this short ballet in the Daily News titled “Enchanting Fire Birds” (September 20 1968) talks of the overall effect of the production: “Gini hora is an exquisite and exotic creation by Vajira; its main beauty lies in its striking visual impact and the compact composition of its skillfully integrated movements. Vajira’s flair for showmanship, her sense of the theatre and her ability to delicately and evenly bind music and movement are all there…The technical perfection with which the fire thieves were transformed into the colourful exotic birds deserves very special mention. It was a very neat transition which carried with it all the elements of an artistically engineered shock. Too soon the birds with their fierce beauty vanished.”

It is in the mid-1980s with the production Shiva Ranga (1986) that Vajira took on more of a central role of director, not only choreographing but also devising the plots and taking charge of other key elements of staging a mudra natya. Vajira’s productions over the decades, staging productions both for her child students and adult members of the company, thus established her status as one of the main figures in traditional dance on the Sri Lankan stage. Strikingly, from a global perspective the role of choreographer, even in contemporary dance, continues to be male dominated in many contexts but Vajira and her South Asian counterparts have created a strong and vibrant female tradition that remains to this day, exemplified by the women who currently head the Chitrasena Dance Company and Kalayathanaya.

An abridged version of this article appeared in the Sunday Times on March 21, 2021. The material for this article is drawn from research on a soon-to-be published book by the author on Chitrasena.