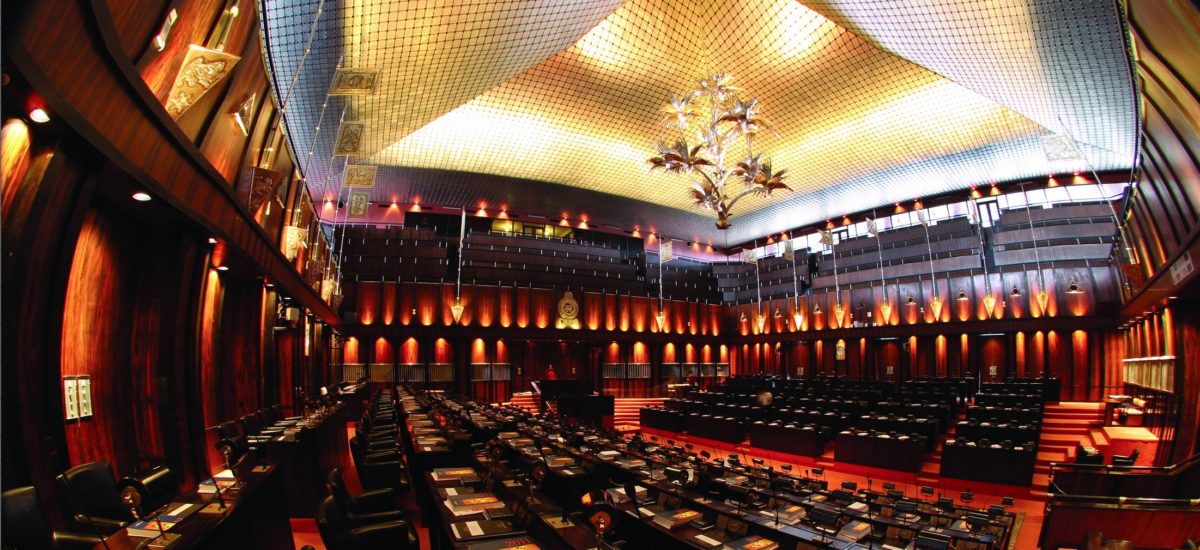

Photo courtesy of indi.ca

These could be the last days of the Nineteenth Amendment. If not of its entirety, at least of a part of it, even a substantial part of it. The message that the Nineteenth Amendment retards effective governance and should be thrown out has reverberated strongly, especially since the Presidential election last year. President Gotabaya Rajapaksa has had enough of it. So, it may go.

The Nineteenth Amendment was possible due to many reasons. A majority of the voting population demanded some reformation of the structure of constitutional governance that prevailed at the time. The Executive President was considered to be too powerful; the President’s powers had to be trimmed. There was a need for a framework that established more independent institutions. Some enhancement of the rights of citizens was also expected. Such demands gradually transformed into a grand political promise. When the time was ripe, when the election had arrived, that promise was best articulated by the movements which opposed the rule of former President Mahinda Rajapaksa. The movements that opposed him were many; their ambitions, varied and even conflicting. But the Nineteenth Amendment gave expression to some of the basic aims and desires of the majority that voted at the Presidential election in 2015. Without this popular support, the Nineteenth Amendment, or anything like it, would not have been possible.

The Nineteenth Amendment was also possible due to the support extended by the overwhelming Parliamentary majority which represented the Rajapaksa regime. Mahinda Rajapaksa’s loss at the Presidential election did not affect the Parliament’s composition during that interim period between January and August 2015 (when the General Election was held). Some two-thirds in Parliament supported Rajapaksa. Thus, it was clear that the Nineteenth Amendment was impossible without the Rajapaksa regime’s support. Its support was essential; and its support was given. Ultimately, there was a long debate. The voting went into the night. And finally, in a Parliament of 225, 212 Members supported the adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment. Surprising many observers, the Nineteenth Amendment was passed with an unprecedented and staggering majority.

Why did the Rajapaksa regime support it? Fundamentally, it was a consequence of the tectonic shift in leadership that had taken place with the defeat of Mahinda Rajapaksa. The defeat was too remarkable to be ignored. And the Rajapaksa regime did not want to be seen as the sole factor that blocked a reformist move which was, in broad terms, supported by the majority of the population. A perusal of the Hansard of April 2015 also shows that the Nineteenth Amendment Bill was able to attract the support of the regime because it was backed by President Maithripala Sirisena and strongly promoted by a figure like Ven. Maduluwawe Sobitha. Sirisena was, after all, one of their men who had crossed over. Ven. Sobitha was, after all, much respected for his role as a politically conscious monk (with an interesting history of nationalist political agitation behind him).

Beneath this shift was also the silent opposition of certain members of the Rajapaksa regime towards the Eighteenth Amendment, adopted in 2010. With their leader out of power, many within the SLFP felt that it was time to correct the mistakes made by the Eighteenth Amendment. Interestingly, the most prominent doubt that the Rajapaksa regime’s stalwarts had about the Nineteenth Amendment Bill was simply this: that it would be used by Prime Minister Ranil Wickremasinghe to increase his powers. That was really the debate about the Nineteenth Amendment then. The discourse surrounding the Nineteenth Amendment has changed so much today that the speeches made in Parliament by the regime’s most vociferous supporters may surprise many political observers.

The Nineteenth Amendment, then, was not an accident. And it was not only a contribution of the Sirisena-Wickremasinghe interim regime. Rather, it was a consequence of a conscious effort and decision taken by a series of stakeholders. A majority of the Sri Lankan population supported it. Most crucially, the Rajapaksa regime supported it. And it was a regime that knew what it was supporting.

Has the Nineteenth Amendment been of any use since its adoption? It did a number of important things. At a time when the Executive Presidential system had become almighty, the Nineteenth Amendment came and established a system in which the President and Prime Minister had to share power. At a time when the President had almost unfettered powers to establish public institutions and appoint persons to the top positions of the state, the Nineteenth Amendment returned with a Constitutional Council, promising the possibility of establishing more independent institutions and personnel that better served the public interest. The Nineteenth Amendment also enhanced the rights of citizens by introducing the invaluable right to information. It also limited Presidential immunity. Its full impact was ultimately felt when the Supreme Court ruled against President Sirisena’s decision to appoint Mahinda Rajapaksa as Prime Minister in 2018. The Nineteenth Amendment had served its purpose.

However, the Nineteenth Amendment needs to be understood for what it is; not for what it ought to have been. For example, the Nineteenth Amendment did not abolish the Executive Presidency. It does not prevent the President from holding the post of the Minister of Defence. In suggesting that the Nineteenth Amendment did such fantastic things, the supporters of the Nineteenth Amendment may have done more harm than good. Why? Because in showing that some of those fundamental powers of the President were limited, they made the Nineteenth Amendment look like an absurdity, thereby helping to generate (unwittingly) greater opposition to the Nineteenth Amendment, especially within the Sinhala majority. Also, the importance of a crucial part of the Nineteenth Amendment – the part which shifts the powers from the President to the Prime Minister/Cabinet of Ministers and the Parliament – is only contextual. In a country where the President and Prime Minister represent the same party, with the latter following the former, this part of the Nineteenth Amendment would be useless. And where the individual commissioners appointed to institutions do not act in ways that promote the principle of independence, the Nineteenth Amendment would be of little use.

The Nineteenth Amendment was an important and necessary corrective to our way of constitutional governance when it was introduced in 2015. It ought to have changed how the people and their representatives thought about some of the fundamentals of constitutional governance. But it sits awkwardly in a Constitution that was meant to promote a different way of governing the state and it continues to live precariously in a society that wishes to go back to that different way of governing the state. Very soon we may see that that way is the normal way.

Five years after the Nineteenth Amendment was adopted, Sri Lanka has a new political leader. Very soon, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa will have a new and popular government with him. In his journey from being the former Defence Secretary to the current Executive President, one of his most trusted allies, one who is closest to President Rajapaksa ideologically, has been Rear Admiral Sarath Weerasekera. Set to return to Parliament with renewed support and great gusto, Weerasekera was the only Member of Parliament who, in 2015, voted against the Nineteenth Amendment Bill. That is the ideological force that stares in the face of the Constitution today. If the Nineteenth Amendment had hands and feet, it would have already packed up. It would be standing at the gate. It would be ready to leave. In a country of fabulous political ironies, it may find that only Mahinda Rajapaksa could save it from here.