When over the weekend, senior journalist Amantha Perera sent a link to a post on Facebook asking if it was one that was popular, the answer took me into a brief study of the news and information ecology of a complex, long-standing issue extensively covered on Groundviews, currently rendered through predominantly racist frames. In Wilpattu: Apportioning the blame game, journalist Thulasi Muttulingam cogently and succinctly draws the faultlines of a predominantly ill-informed debate at present. What interests me more is how complex media ecologies, on Facebook, seed and spread a framing that dominates the perception of an issue by sheer volume and velocity, even if completely lacking in veracity. This is a corrosive dynamic that contributed to physical, kinetic violence in and around Ampara and Digana a year ago. The prevalence of misinformation around the recent interest and spike in content on Wilpattu, strategically seeded, was confirmed by the BBC. This and more openly violent and rabidly racist content on Twitter added to concerns that a lot of what is produced and promoted at present on Wilpattu is far removed from any real love of or interest in conservation or environmentalism.

A brief exploration of content published on Wilpattu in English and Sinhala (as විල්පත්තු) on Facebook and Twitter, over 7 days, offers a glimpse into contemporary information flows on social media. The data also gives insights into the intentional weaponisation of an issue to seed discontent. All posts, tweets, pages and accounts used or flagged are public. Reports received indicate WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger are heavily used to push content out to groups, each numbering in the hundreds. Though not impossible, the study of news and information exchanged over instant messaging is far more time consuming and labour intensive. Anecdotal evidence suggests the content exchanged in these WhatsApp groups overwhelmingly link back to material on Facebook. Not unlike dynamics in India leading up to the Lok Sabha elections, or what happened in Brazil, scrutiny of instant messaging’s role, reach and relevance in the news and information landscape (academically also known as the ‘agenda setting effect‘) requires more careful study in Sri Lanka. In forging a data-driven response to Amantha’s question, I only had the time to delve into Facebook and Twitter.

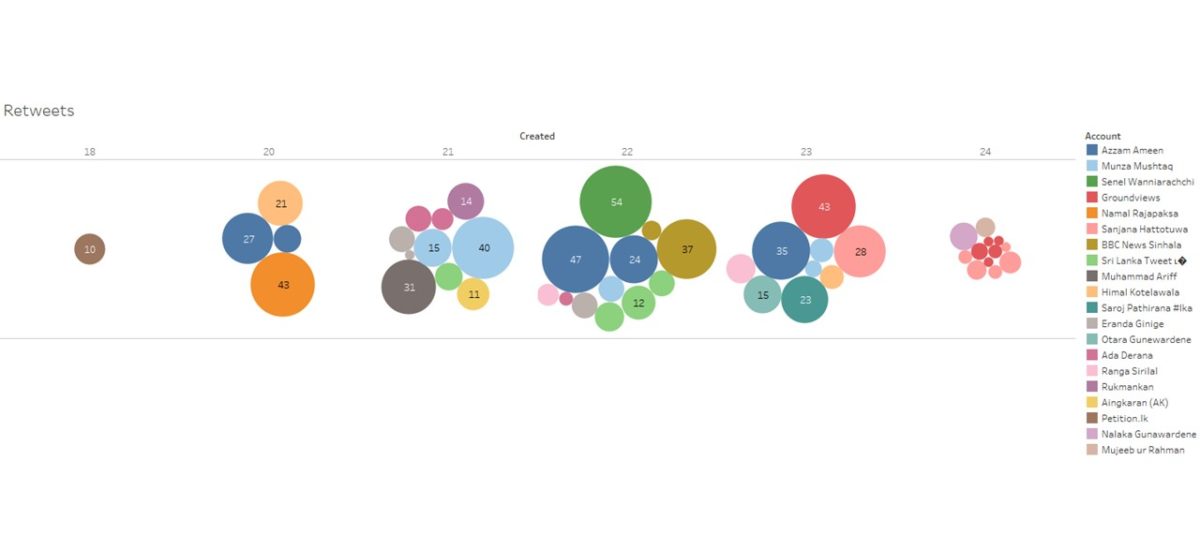

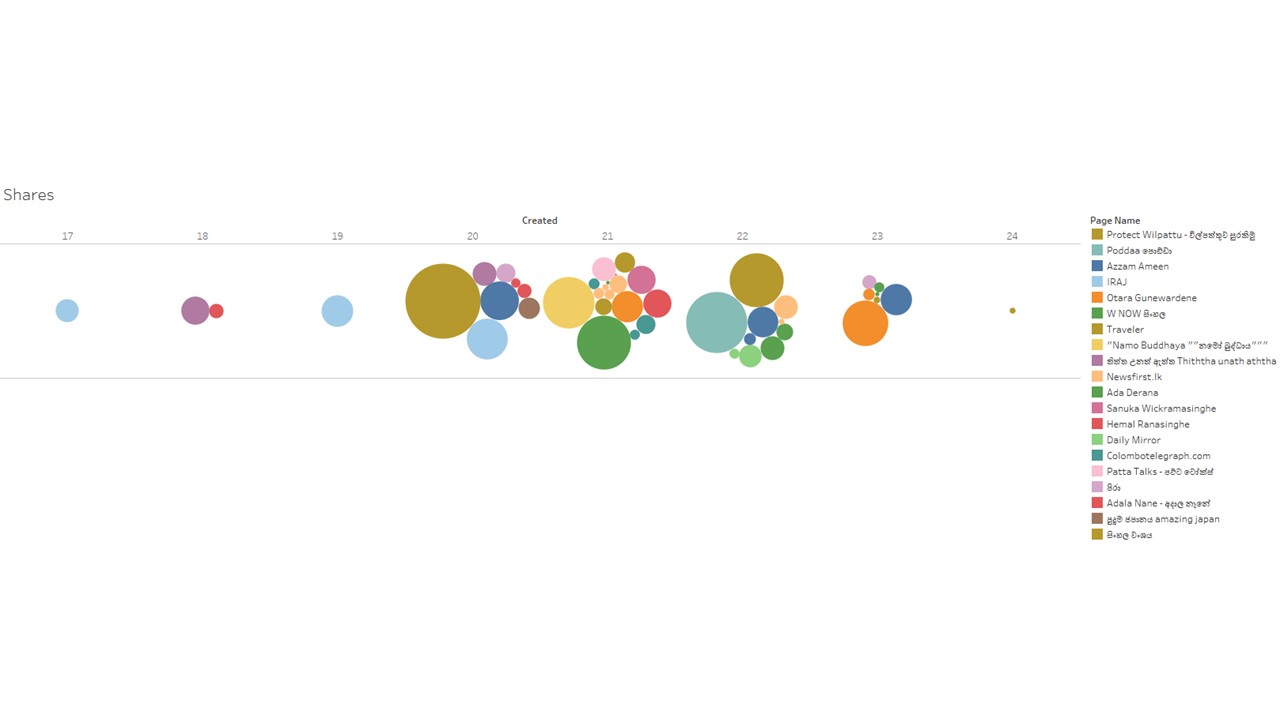

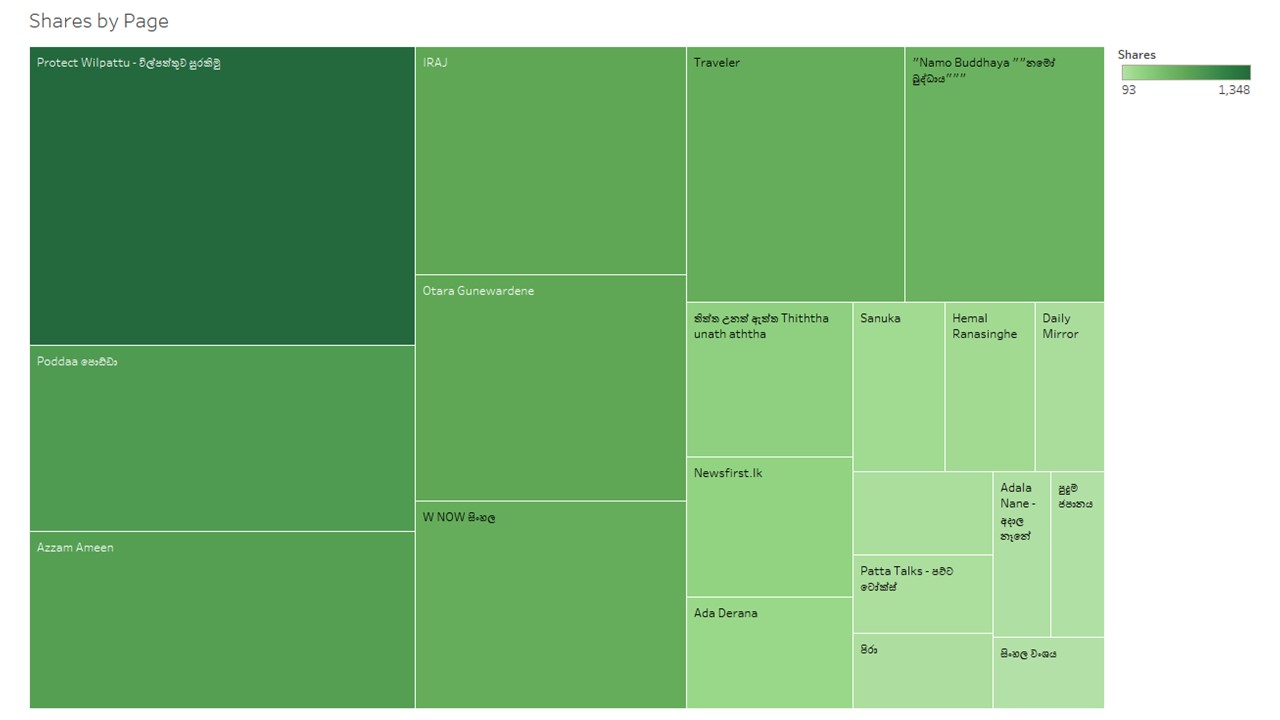

Interest in Wilpattu, in English and Sinhala, on Facebook and Twitter, didn’t really exist before the 20th (Wednesday). Across both platforms and languages, content production on Wilpattu increased dramatically on this day, and remained high for the rest of the time monitored. In English on Facebook, a post by the infamous Iraj on the 17th is the first mention of the term (120 shares), followed by another on the 19th (targetting Bathiudeen, with 225 shares). On the 20th, the ‘Protect Wilpattu – විල්පත්තුව සුරකිමු’ page features the most shared post. Interestingly, this is a poster overtly in opposition to Mahinda Rajapaksa, Basil Rajapaksa, Maithripala Sirisena and Ranil Wickremesinghe, who are portrayed as having protected and promoted Bathiudeen (1,265 shares). Azzam Ameen (335) and Iraj (375) also have highly shared posts on this day. Namo Buddhaya “නමෝ බුද්ධාය” (597 shares), Poddaa පොඩ්ඩා (838 shares) and Traveler (653 shares) feature some of the most shared content over the next days. Otara Gunewardene’s sharing of content from the ‘Protect Wilpattu – විල්පත්තුව සුරකිමු’ page on the 21st (221 shares) and an original post on the 23rd (465 shares) also generate a lot of traction. The post from W Now (with 654 shares) is actually a video in Sinhala. Size of the circle in the graph below corresponds to the number of shares. The legend is ordered from the highest to the lowest number of shares, by account (this general ordering principle applies for all the following graphs).

Click for larger image. Over 7 days, the BBC’s Azzam Ameen is the only account from a recognised journalist in the top five most shared posts.

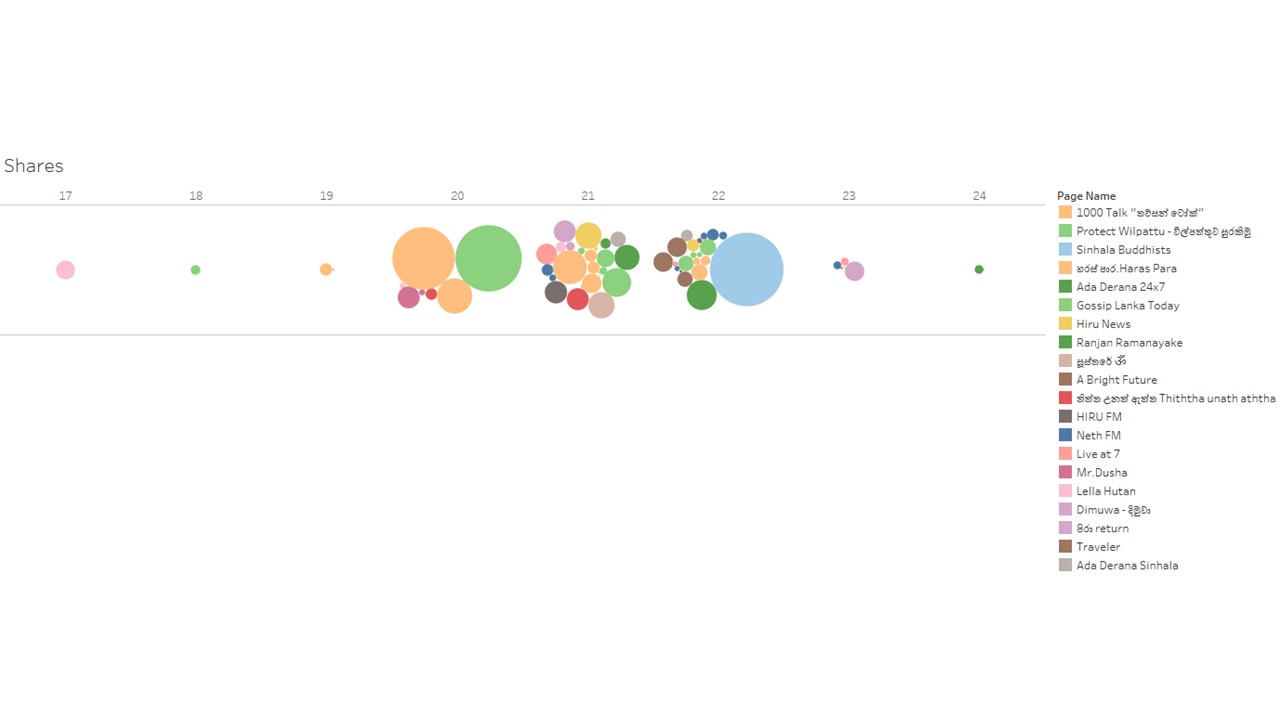

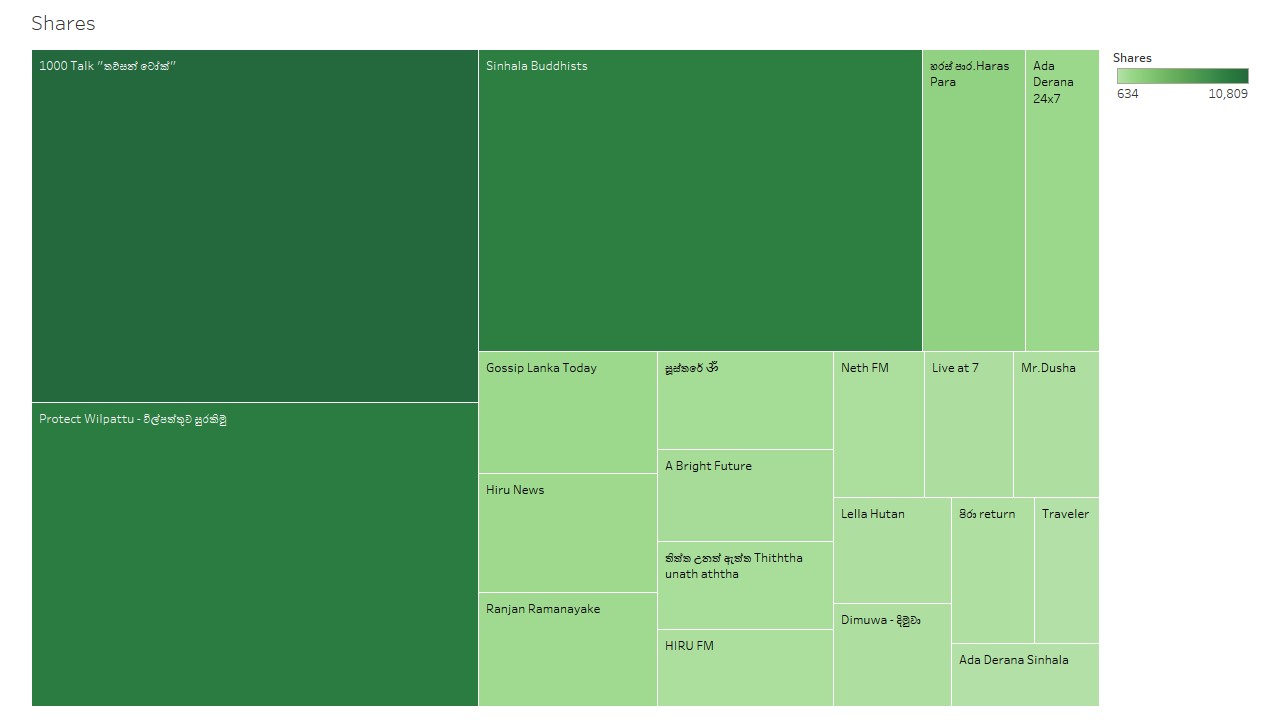

Click for larger image. It’s a different landscape around විල්පත්තු on Facebook. Significantly, the volume of engagement is much higher. There is a far greater number of users, around just this single issue, active on Facebook in Sinhala than over English. A rallying cry to kinetic action posted on the ‘Protect Wilpattu – විල්පත්තුව සුරකිමු’ page generates very high shares (7,495), in addition to posts on the ‘Sinhala Buddhists‘ page (9,185) and the ‘1000 Talk “තව්සන් ටෝක්”‘ page (6,628). The post on the Sinhala Buddhists page features a statement ostensibly made by Gotabaya Rajapaksa. The 20 most shared posts overwhelmingly come from non-traditional media sources or gossip pages.

By far, posts from non-traditional media sources and gossip pages dominate the information landscape in Sinhala. Click for larger image.

Click for larger image. A similar pattern emerges around the most liked content, the most viewed videos and the most commented on posts in Sinhala (see full slide deck below). Interestingly, the most number of comments during this time is on this post on the ‘Sinhala Buddhists’ page.

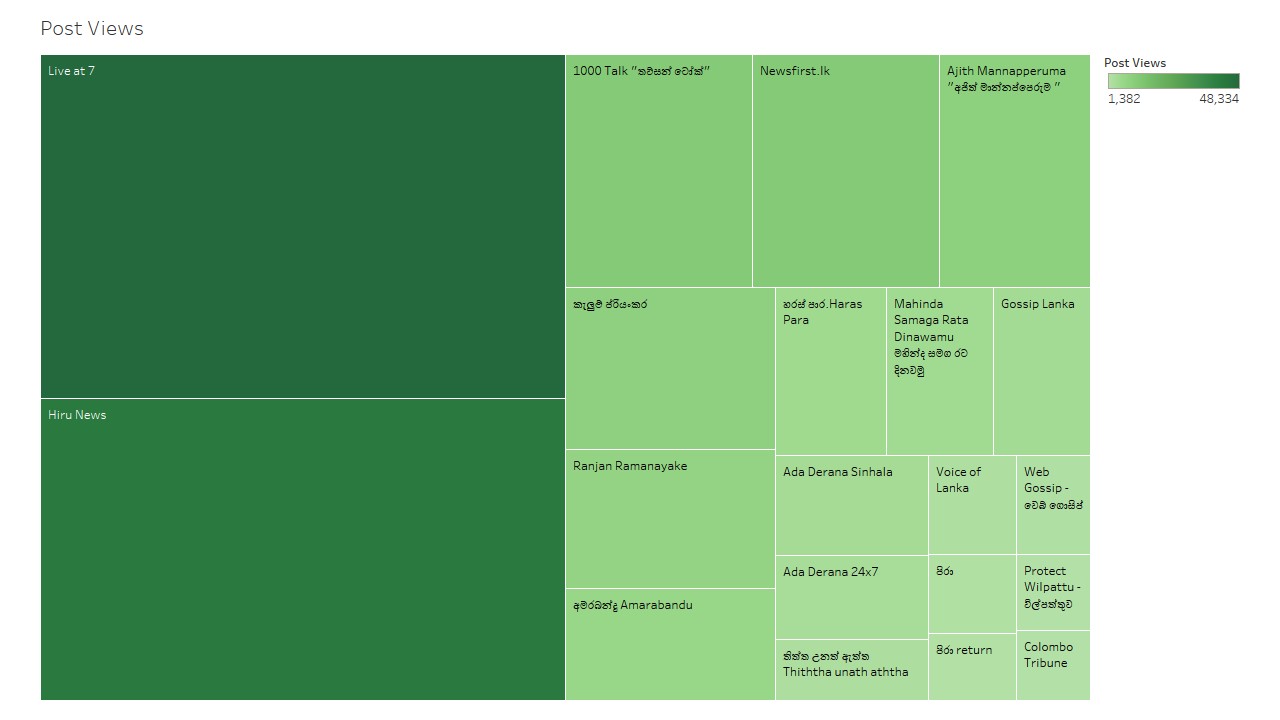

Because video goes viral on Facebook, it is important to look at what pages have generated the most amount of views for videos anchored to Wilpattu in Sinhala. A video posted on the ‘ජන බලය’ page, shared on the ‘Bring Back Gota‘ page (viewed 123,328 times) just edges out the views of, tellingly, the same video featured on the ‘1000 Talk “තව්සන් ටෝක්”‘ page (with 121,518 views). Overall, the eyeballs on videos published in Sinhala during these 7 days reveals the dominance of a particular frame of reference anchored to a reductionism over contextualisation, even on content posted by Hiru, Live at 7 and Ada Derana.

Click for larger image.

A quick takeaway (see full slide deck below) is also that those on Facebook view, like and share (emotive content) by order of magnitude more than they comment on posts (true of content in English and Sinhala). This is a pattern I saw during the constitutional crisis of 2018 as well. Perhaps worth noting is that in English, Azzam Ameen’s page/account generates the most amount of likes and comments, as well as a significantly high number of shares. In the Sinhala page/account eco-system however, Ameen’s content doesn’t feature.

Looking at the Wilpattu issue on Twitter in English, one is struck by how much less engagement there is, overall, in comparison to Facebook. But on Twitter as well, the Wilpattu issue in both languages shows a dramatic increase on the 20th, from next to nothing just the previous day.

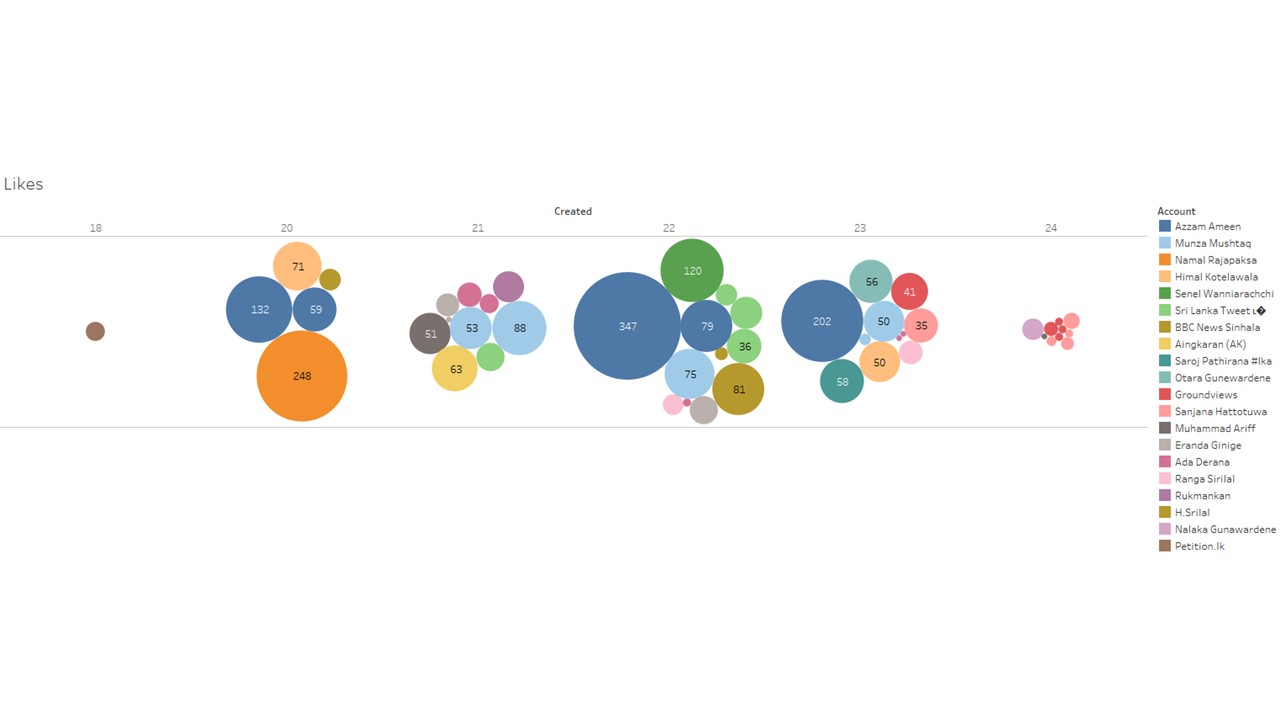

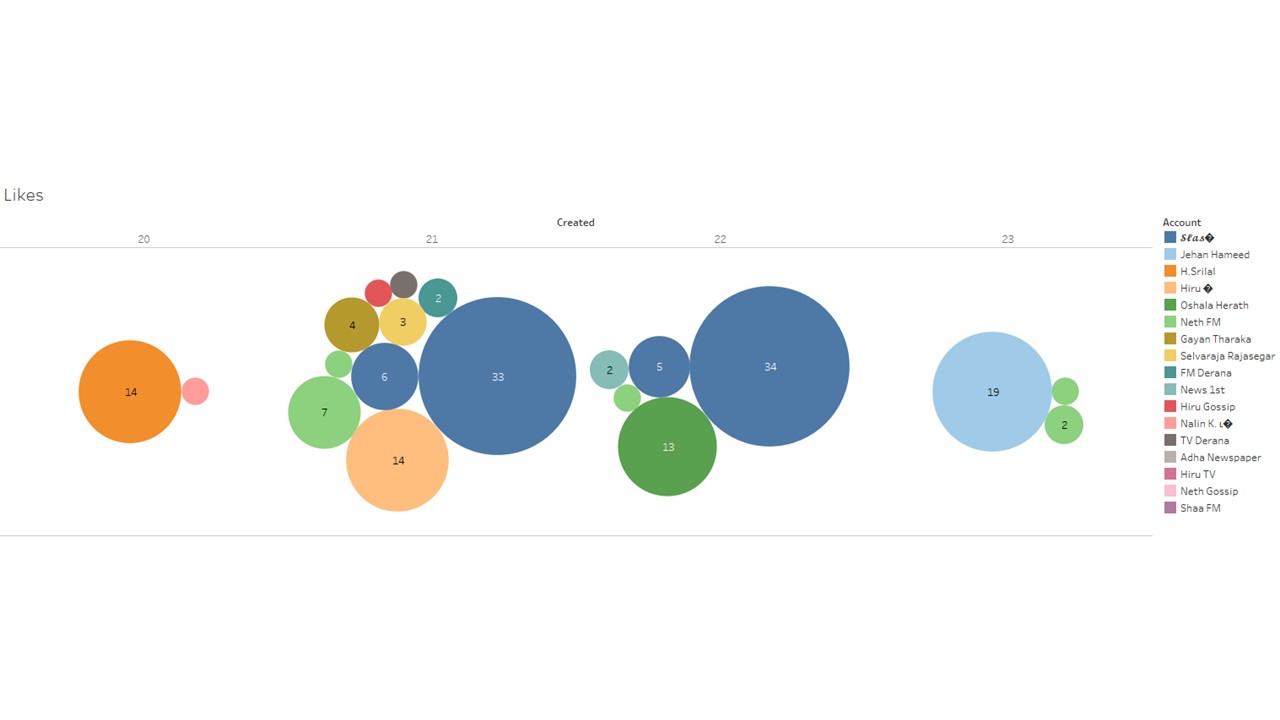

The numbers within each circle indicate the measure of what the graph is anchored to. Below, we look at the number of likes the top 20 most active accounts in these 7 days have generated, tweeting ‘Wilpattu’ in English. As with graphs above, the size of the circle in the graph corresponds to the number of records. For easier reference, I’ve also included the numbers within each circle. The legend is ordered from the highest to the lowest number of likes, by account. Again, this general principle of ordering and presentation applies for the rest of the visualisation.

Click for larger image. Namal Rajapaksa’s tweet, Azzam Ameen’s tweet on the 22nd, followed by the one on the 23rd capture very different foci. These 3 tweets generate, by far, the most amount of likes in these seven days. Though a number of accounts produce tweets, only a few generate significant traction by way of retweets (see full slide deck below).

විල්පත්තු on Twitter features a completely different set of accounts generating content. It also features much less content than English. This is an inversion of the general pattern on Facebook, which produces by order of magnitude more content in Sinhala, over any issue and around any temporal period I’ve studied since 2015 (including during 2018’s constitutional crisis), than in English.

Click for larger image. Two tweets by @DJSlash9, on 21st and 22nd respectively, generate the most amounts of likes. Both posit critical questions around politics and Bathiudeen. A quick scan of this really strange account, which I hadn’t encountered before, reveals the author is interested in everything from quick erections and other phallic issues to tweets against a particular political party. The same account also generates the most amount of retweets during these 7 days, in Sinhala. On the 23rd, a tweet by SLPP’s Jehan Hameed, linking interest in the issue with regime change, generates some interest. The most active producers of tweets are also very different from English to Sinhala. Details in the full slide decks embedded below.

Of particular concern here, on Twitter and especially in Sinhala on Facebook, is the commentary (or responses) to content posted. I will not link to specific posts or tweets to avoid the oxygen of greater publicity or promotion. But as I noted on Sunday, the commentary includes outright calls for violence.

[There are] repeated calls to hang or kill Member of Parliament and Minister Rishad Bathiudeen for his perceived role in the purported deforestation of Wilpattu. One tweet made explicit reference to the recent terrorism in New Zealand, noting that if Bathiudeen wanted to transform Sri Lanka into a Saudi Arabia, the author of the tweet was ready to do what the Australian in Christchurch did. Another tweet quotes a Buddhist monk noting that Bathiudeen should be hanged and killed. The rule of law, due process, robust investigations and the role of democratic institutions are rendered entirely unnecessary to, or weak in the face of what is taken to be, projected and strategically promoted as violence against Sinhala Buddhists by Muslims. Fascism, violence, theocratic fiat and communal uprising are the leitmotifs of this discourse.

In sum, the conversational domain around Wilpattu, since just the 20th, is mired in overwhelming toxicity, with rabid, racist, extremist content aimed at a specific community, faith and culture. This aside, overarching observations around information ecologies on social media in Sri Lanka are congruent with and reaffirm findings in a brief study on the thrust and timbre of discussions on Facebook around constitutional reform, since 2015. Recalling recommendations (d), (e) and (f) made in a Policy Brief on social media in Sri Lanka written in 2018, this study captures the very different dynamics between Facebook and Twitter, as well as, on each platform, between English and Sinhala.

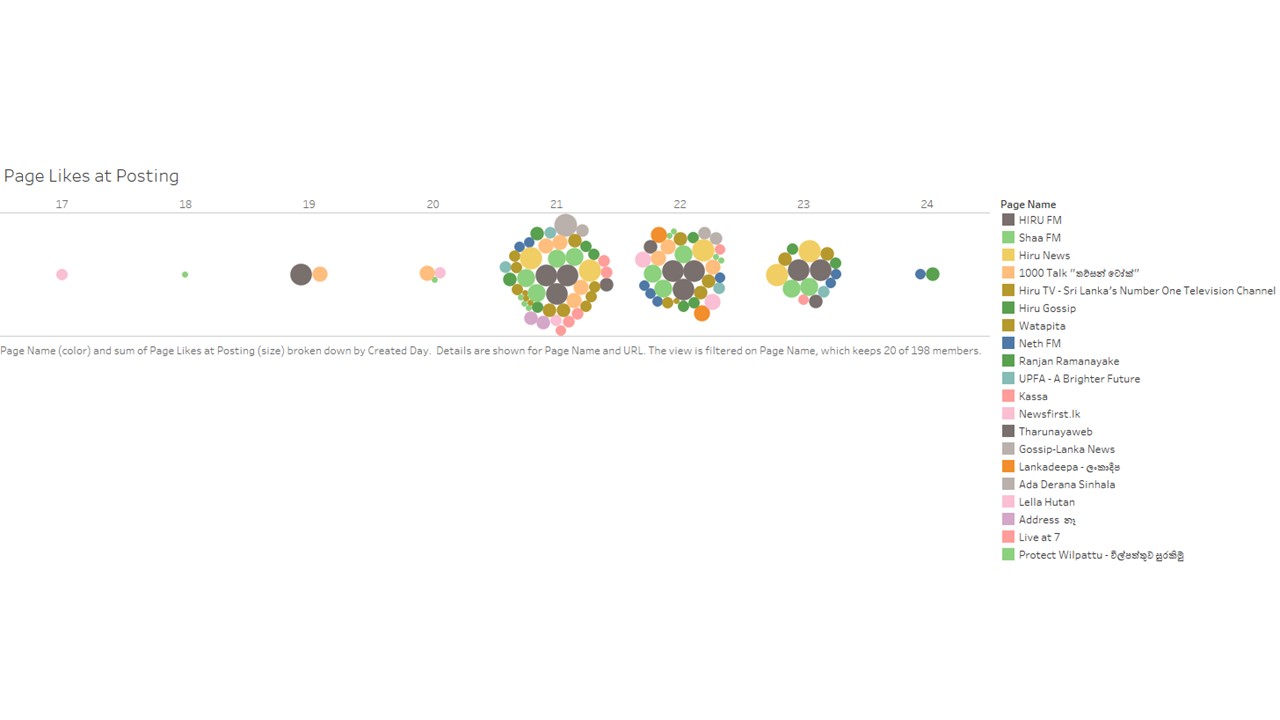

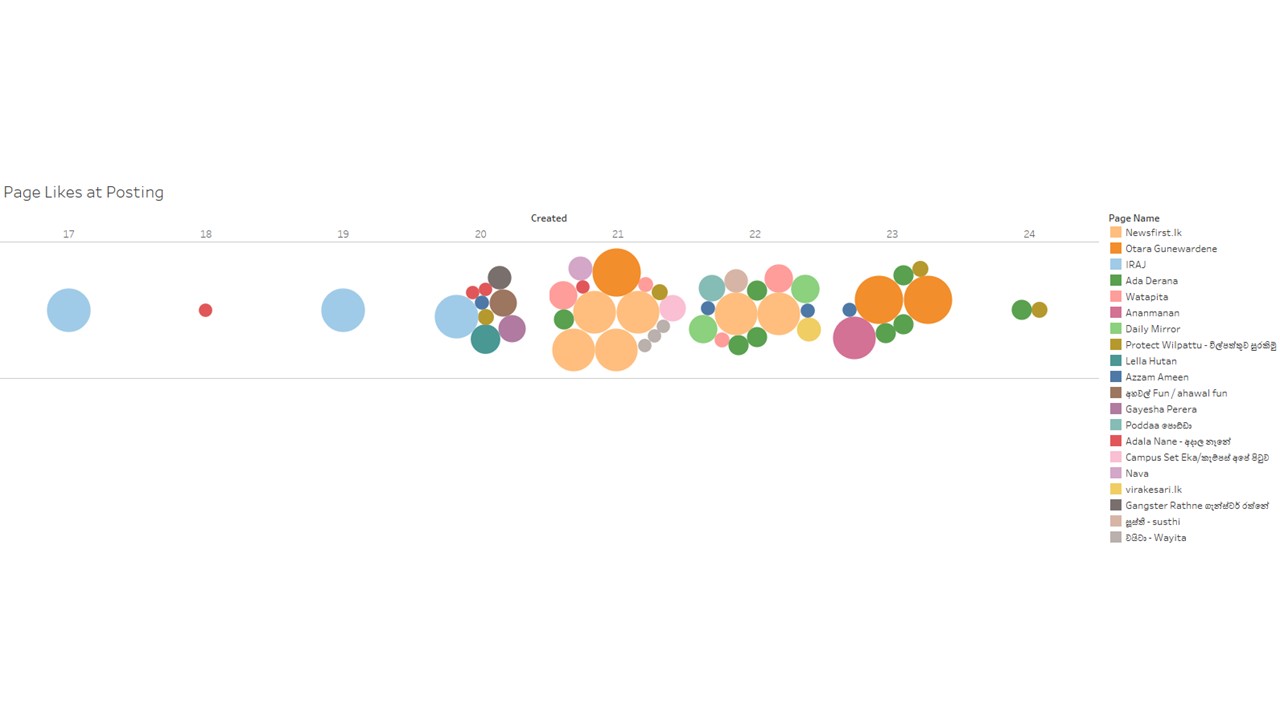

Focussing on these points matters. Though measuring influence is subject to many caveats and differing methods, one metric is to look at the number of likes (i.e. fans, followers or subscribers) a page promoting an issue has (at the time a post goes up). This is indicative of the potential audience (even though the actual audience is subject to the vagueries of Facebook’s News Feed algorithm and personal preferences).

These are the pages with the most amount of likes featuring content in Sinhala.

Click here for larger image. And these are the pages with the most amount of likes featuring content in English.

Click here for larger image.

The top five pages in Sinhala are, in descending order: Hiru FM (1,816,575), Shaa FM (1,251,158), Hiru News (1,925,501), ‘1000 Talk “තව්සන් ටෝක්”‘ (894,141) and Hiru TV (708,279). The five top pages in English are, again in descending order: Newsfirst.lk (1,058,433), Otara Gunewardene (1,331,188), Iraj (1,087,099), Ada Derana (233,597) and ‘Watapita’ (463,926).

Potentially then, the framing, foci, expression, tropes, content and (toxic) commentary on the five most followed pages in Sinhala could have reached up to around 6.6 million accounts. In English, the potential reach was around 4.2 million accounts.

Carefully read alongside other multivariate metrics of production, influence and engagement, these numbers and their associated accounts indicate, prima facie, that key drivers of conversation on Facebook differ dramatically depending on which language is employed. Secondly, the numbers – even at a very conservative, cautious reading – indicate the scale and scope of information transversal on social media, encompassing non-traditional, traditional, gossip, reputed, unknown, well-known media actors variously trusted, perceived and engaged with. Finally, simplistic readings of social media’s role in spawning racism (and any kinetic violence) must be eschewed for more nuanced, sustained studies in how complex online dynamics both play out through and play on socio-political, communal and identity faultlines that thrive post-war.

###

Presentations hosted on Google Slides covering the points noted above and with much more information can be viewed below. Share freely with attribution. The author is the Founding Editor of Groundviews. He is currently pursuing doctoral studies at the National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies (NCPACS), University of Otago.