Sitting on Maatram Editor Selvaraja Rajasegar’s desk is a thick envelope containing details of elephant deaths on the railway track. The information took him over a month to receive, because he made the request in Tamil. The response, when it eventually came, was in English.

This is not unusual – as someone who requests in Tamil, Maatram’s requests will often only be responded to in a month’s time, if at all.

Vikalpa Editor Sampath Samarakoon meanwhile, says that those who file in Sinhala do not face the same barriers.

Both Maatram and Vikalpa have been active in applying for information under the Right to Information Act since it was operationalised in 2016. They are colleagues who file requests on similar issues. But their experience of using the Act is very different. This does not just reflect structural issues within the Government departments that they have applied to – it reflects language barriers that ordinary citizens continue to face in accessing essential services.

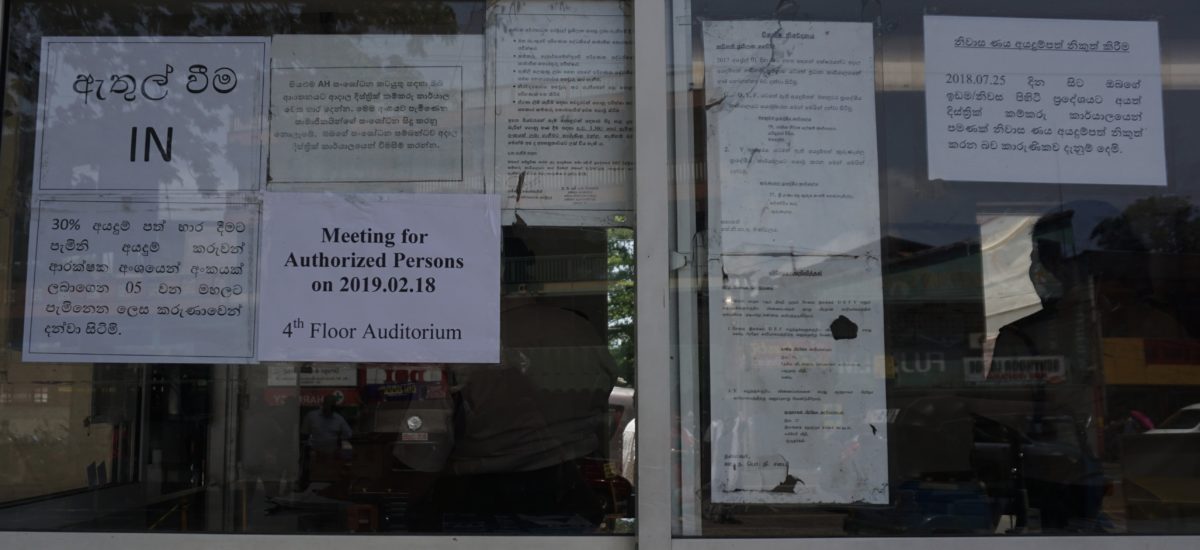

A 2017 survey by the Centre for Policy Alternatives found that all the main name boards in Ministries were in line with the Official Languages Policy, although section name boards and designation boards were not always trilingual. Just four Ministries had a public announcements system that was in line with the Languages Policy.

Despite a 2007 circular specifying that all State sector employees must gain proficiency in a second language within five years of employment, just 2% of employees had scored over 75% in 2015 and 2016.

The Consultation Task Force of Reconciliation Mechanisms in its final report pointed out the lack of bilingual proficiency within the State sector, and the barriers it posed for ordinary people accessing services.

February 21 marked International Mother Language Day. It is worth reflecting on these divisions and how they continue to impact citizens today.