Further exacerbating the constitutional crisis that he precipitated a fortnight ago, President Sirisena issued a proclamation purporting to dissolve Parliament on 9thNovember 2018. Having prorogued Parliament and then lost the gamble to cobble together a majority for his new illegal government through corrupt means, he has gone further down the path of unconstitutional action by this dissolution. The legality of the dissolution has been hotly debated, with the provisions of Articles 33, 62, and 70 of the Constitution being subject to conflicting interpretations on the question of whether or not the President has a unilateral power to dissolve Parliament. It is important to note that each of these provisions were materially amended by the Nineteenth Amendment in 2015, and these changes go to the heart of the current disagreements over the power of dissolution. For ease of reference, the relevant extracts of the Articles as they are after the changes made by the Nineteenth Amendment are as follows:

Article 33

(2) In addition to the powers, duties and functions expressly conferred or imposed on, or assigned to the President by the Constitution or other written law, the President shall have the power –

(c) to summon, prorogue and dissolve Parliament

Article 62

(2) Unless Parliament is sooner dissolved, every Parliament shall continue for five years from the date appointed for its first meeting and no longer, and the expiry of the said period of five years shall operate as a dissolution of Parliament.

Article 70

(1) The President may by Proclamation, summon, prorogue and dissolve Parliament:

Provided that the President shall not dissolve Parliament until the expiration of a period of not less than four years and six months from the date appointed for its first meeting, unless Parliament requests the President to do so by a resolution passed by not less than two-thirds of the whole number of Members (including those not present), voting in its favour.

(3) A Proclamation proroguing Parliament shall fix a date for the next session, not being more than two months after the date of the Proclamation:

Provided that at any time while Parliament stands prorogued the President may by Proclamation –

(i) summon Parliament for an earlier date, not being less than three days from the date of such Proclamation, or

(ii) subject to the provisions of this Article, dissolve Parliament.

(5) (a) A Proclamation dissolving Parliament shall fix a date or dates for the election of Members of Parliament, and shall summon the new Parliament to meet on a date not later than three months after the date of such Proclamation.

(b) Upon the dissolution of Parliament by virtue of the provisions of paragraph (2) of Article 62, the President shall forthwith by Proclamation fix a date or dates for the election of

Members of Parliament, and shall summon the new Parliament to meet on a date not later than three months after the date of such Proclamation.

(c) The date fixed for the first meeting of Parliament by a Proclamation under sub-paragraph (a) or sub-paragraph (b) may be varied by a subsequent Proclamation, provided that the date so fixed by the subsequent Proclamation shall be a date not later than three months after the date of the original Proclamation.

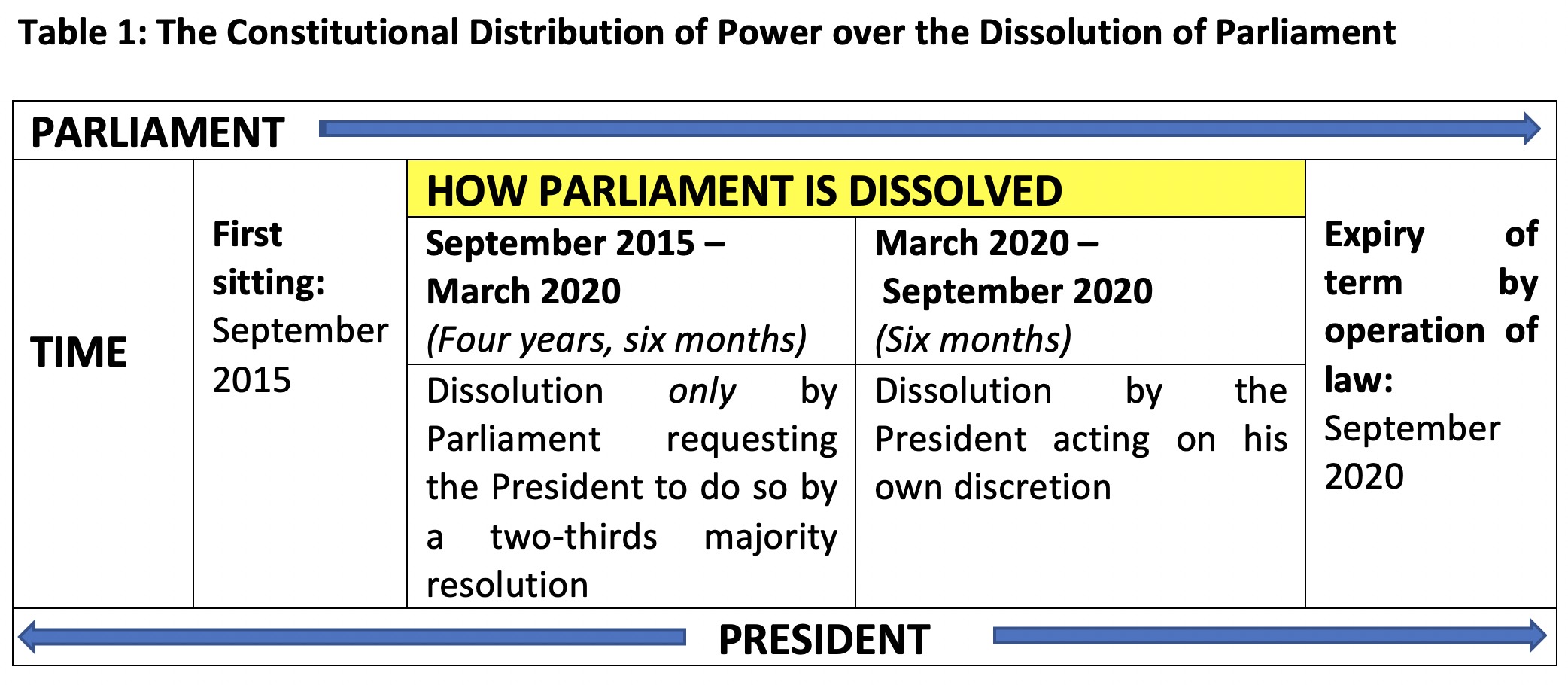

What all this means in plain language is that Article 33(2)(c) identifies the President as the constitutional actor who dissolves Parliament, which in terms of Article 62(2) is elected for a term of five years, and unless sooner dissolved, it expires at the end of that period by operation of law. In terms of Article 70(1), an early dissolution of Parliament can be activated in two different ways: (a) in the first four and a half years of Parliament’s term, when Parliament itself requests the President to do so, by a resolution passed with the support of a two-thirds majority; and (b) in the last six months of Parliament’s term, by the President acting on his own volition. Article 70(3) provides for a dissolution at a time when Parliament is prorogued, subject to the limits in Article 70(1). Article 70(5) simply requires the proclamation of dissolution to set out the modalities for general election to follow, and the meeting of the new Parliament. This is to ensure that a President cannot dissolve a Parliament without also making provision for the election and meeting of the next Parliament in due time.

This describes the constitutional framework for dissolution after the Nineteenth Amendment. While preserving many aspects of the previous framework, the Nineteenth Amendment changed the relationship between President and Parliament in this regard in two critical ways. First, it reduced the scope of the President’s power over dissolution temporally, by expanding from one year to four and a half years the period during which Parliament was protected from a unilateral presidential dissolution. Second, itprocedurally strengthened Parliament vis-à-vis the President by raising the required threshold of support for a parliamentary resolution for early dissolution from a simple to a two-thirds majority. The effect of these two changes was to rebalance the relationship between President and Parliament towards more of an equilibrium than had hitherto been the case under the 1978 Constitution.

All this was in the gazetted Nineteenth Amendment Bill which was considered by the Supreme Court in its pre-enactment determination in 2015. Unlike certain other clauses in the Bill to reduce the powers of the President, the Court did not find that these changes required a referendum. Similarly, there were clauses that were fiercely opposed, debated, and changed in the Bill during the parliamentary debate, but these provisions survived in the Nineteenth Amendment Act, which was passed with near unanimity in Parliament including with the votes of the Rajapaksa loyalists. Having passed judicial and legislative muster according to the established constitutional amendment procedure, these were therefore valid and agreed constitutional changes brought in by the Nineteenth Amendment, even though now the President who gave leadership to the entire process in 2015 has decided to act in complete contravention of them. And there is no truth whatsoever to the claim made in some quarters – and reported uncritically by respectable newspapers – that this was an innovation smuggled in by stealth at Committee-stage, thus robbing the Supreme Court of an opportunity to review its constitutionality. The record simply does not bear out this scandalous falsehood.

Why is the purported dissolution of 9thNovember unconstitutional?

Article 33 is a general provision which describes the duties, powers, and functions of the President of the Republic. In its substituted form after the Nineteenth Amendment, all previous functions in relation to Parliament such as making the Statement of Government Policy and presiding at ceremonial sittings of Parliament were preserved. But the new Article 33 had two significant additions. These were, first, the addition of a statement of the constitutional duties of the President, including the duty to ensure that the Constitution is respected and upheld (Article 33(1)(a)). Secondly, the presidential role in summoning, proroguing, and dissolving Parliament was brought into this statement of general functions (Article 33(2)(c)). This had previously been stated at Article 70, which was a provision that was significantly reformed by the Nineteenth Amendment. Reinforcing these powers and duties given by Article 33 is Article 33A immediately after it, which establishes the principle that the President is responsible to Parliament for the discharge of his powers, duties and functions. This principle was recognised even before the Nineteenth Amendment, but it seems to have been relocated to its present position to buttress the new statement of presidential duties, powers, and functions. Given also that the provision has been moved from Chapter VIII on the Cabinet to Chapter VII on the President, this was also more logical in underscoring the greater distinction between the President and the Cabinet of Ministers in the reformed – more classically semi-presidential – institutional form of the executive established by the Nineteenth Amendment (about which, more below).

Article 70, concerning the sessions of Parliament, sets out procedures for the summoning, prorogation, and especially the dissolution of Parliament. It is, as noted, a provision the underlying principle of which was significantly reformed by the Nineteenth Amendment, even though many of the other rules it established have been preserved verbatim. Thus, Article 70(2) to (7) are the same before and after the Nineteenth Amendment. But the amendment by the Nineteenth Amendment of Article 70(1) entailed a major change of constitutional principle in that it introduced the principle of fixed-term Parliaments into our Constitution (about which, more below). Previously, Article 70(1) was organised in the form of a power-conferring provision subject to a series of provisos that specifically limited the general power conferred in various ways and situations (old Article 70(1)(a) to (d)). The most relevant of these limitations to this discussion was that the President’s general power of dissolution was specifically limited by provisos (a) and (b), to the effect that the President could not dissolve Parliament in the first year of its (then) six-year term, unless Parliament itself requested a dissolution by a simple majority resolution. In the new Article 70(1) as reformulated by the Nineteenth Amendment, it is simply stated that the President may dissolve Parliament from time to time, except in the first four and a half years, during which the President may only dissolve Parliament at the request of Parliament expressed through a resolution passed by a two-thirds majority.

In one sense, therefore, all that the Nineteenth Amendment did was simply to increase the time period and majority threshold in relation to a type of restriction on the presidential power of dissolution that the 1978 Constitution had always recognised. But it is also something more than that, as I will argue below, but let us conclude the discussion about the interpretation of the Constitution first. Thus, we can see how Article 33(2)(c) lays out the general role of the President over dissolution as one of the President’s constitutional functions. However, the proviso to Article 70(1) specifically restricts this power, by requiring it to be exercised only pursuant to a request of Parliament in the first four and a half years. It is a standard rule of interpretation – generalia specialibus non derogant– that a generalprovision (such as Article 33(2)(c)) can onlybe read subjectto a specificprovision (such as Article 70(1)). Thus, the specific restriction in Article 70(1) prevails over the general power in Article 33(2)(c). The current Parliament first met after the last general election in September 2015. This means that it is protected from a unilateral dissolution by the President until March 2020 (see Table 1, above). If before this time, the President acts in excess of the defined authority given to him by the Constitution by purporting to dissolve Parliament without a request from Parliament in the required form (i.e., a resolution passed by a two-thirds majority), it follows that any such purported dissolution is unconstitutional and of no legal effect.

Three further points may be addressed. Defenders of the recent presidential action make much of the phrase in Article 33(2), “In addition to the powers and functions expressly conferred…on…the President by the Constitution or other written law, the President shall have the power to…dissolve Parliament” to argue that the power of dissolution under this provision is independent of any other provision, and as such is protected from the restriction as found in Article 70(1). They further point to Article 70(5) which sets out various requirements that the President must fulfil in making a proclamation of dissolution as evidence of the existence of an independent power, which also contains a reference to Article 62(2). They then adduce the first clause of Article 62(2) “Unless Parliament is sooner dissolved, every Parliament shall continue for five years…” to buttress the point that early dissolution by unilateral presidential action is preserved even after the Nineteenth Amendment.

This is a wholly unpersuasive line of argument, and not merely because of its tortuous and ambiguous logic. When a clear and principled interpretative approach with which to read Article 33 and 70 together as I have outlined above is readily available, why should we resort to such convoluted and devious reasoning other than to advance improper and ultimately unconstitutional ends? The phrase ‘in addition to’ does not confer on the power under Article 33(2)(c) any independent character; it merely describes in general terms one of the functions of the President alongside many others. Article 70(1), in its power-conferring limb, only repeats or complements the description of the same presidential function as in Article 33(2)(c), before imposing the crucial limitation on that power by its proviso. The limitation of the power of the President in relation Parliament was the whole underlying point and purpose of the Nineteenth Amendment, and it is totally implausible to argue that its framers chose in these ways to surreptitiously preserve a presidential power that they had otherwise directly sought to remove. And as noted before, there is no greater significance to Article 70(5), which only concerns certain safeguards to ensure the continuation of the legislative branch after elections, or to Article 62(2), which establishes the general five-year term limit of Parliament, unless it is dissolved earlier according to the procedure in Article 70(1). That is, either with a parliamentary resolution in the first four and a half years, or by a unilateral presidential proclamation in the last six months of Parliament’s term.

There is also a final source of support for my argument from the text of the Constitution, and this relates to a situation where the President has to dissolve Parliament during a time when Parliament stands prorogued. Those are exactly the circumstances that prevailed when the purported dissolution was proclaimed on 9thNovember, but the application of Article 70(3)(ii) further highlights the unconstitutionality of the President’s action. The relevant extract of Article 70(3)(ii) is “Provided that at any time while Parliament stands prorogued the President may by Proclamation…subject to the provisions of this Article, dissolve Parliament.” The italicised words highlight that a dissolution during prorogation can only occur subject tothe provisions of Article 70, which as we know in paragraph (1) states that the President cannotdissolve Parliament in the first four and half years without a request from Parliament itself. Absent that request, which is the necessary condition precedent to a legal dissolution, the President’s action violates the Constitution in even more specific terms than usual, because the purported dissolution took place while Parliament was prorogued.

So much, then, for the interpretative dispute, which really needs not even take place but for the mendacious and irresponsible arguments being proffered by the defenders of the President’s indefensible behaviour to muddy the waters of public discourse. But there is something more important missing from this debate, and that is a discussion of some of the deeper conceptual issues implicated in the reforms made by the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution. Almost entirely because the government responsible for this far-reaching piece of democratic constitutional reform has been so unutterably deficient in communicating with and educating the public about the changes it made, the public discussion about the Constitution during this constitutional crisis is dominated by personalities and interests to the exclusion of the basic concepts and values that ought to inform public choices. It is no surprise that disinformation thrives in such a context. Two broad matters are especially important in this regard: the semi-presidential system of government, and the fixed-term Parliaments principle.

Semi-presidentialism: Power-sharing and Accountability

Semi-presidentialism is the model of government that underpins our constitutional system, and it is an arrangement that is aimed at securing two major goals of constitutional democracy: (a) power-sharingwithin the executive; and (b) executive accountabilityto the legislature. Seen in its best possible light, this hybrid model aims at combining the democratic and efficiency benefits of both pure presidentialism and pure parliamentarism, while eschewing the disadvantages of the two more traditional models, such as the centralisation of power, deficient accountability, and governmental breakdown.

In the current constitutional crisis, properly characterising the framework of government that is established by the Constitution is crucial to our understanding of the division of power and responsibilities, and the checks and balances that are constitutionally entrenched withinthe executive between the President, and the Prime Minister and the Cabinet, one the one hand, and betweenthe Parliament and the executive, on the other. In this way, such an understanding tells us how each of these institutions and offices should function, and how people elected to them should behave. This allows us to make informed choices and value judgements as democratic citizens, as we will be the ultimate judges of the legitimacy or otherwise of the perpetrators of the constitutional coup.

The 1978 Constitution, before the Eighteenth Amendment and especially after the Nineteenth Amendment, is a classic representation of Gaullist semi-presidentialism. The Nineteenth Amendment was clearly a significant recalibration of the institutional balance of power in the state, so much so that it can be plausibly characterised as transforming the 1978 Constitution from a ‘president-parliamentary’ to a ‘premier-presidential’ model of semi-presidentialism (to use the canonical typology of semi-presidential sub-types developed by Matthew Shugart and John Carey). One of the foremost academic authorities in this area, Robert Elgie, defines the essence of semi-presidentialism as “where a constitution includes a popularly elected fixed-term president and a prime minister and cabinet who are collectively responsible to the legislature.” Thus, executive power is shared between the directly elected President, and the Prime Minister and Cabinet, who in our case are members of the legislature, being collectively responsible to the legislature. They exercise executive power together in defined but overlapping ways, and cooperation is essential to the model’s success. That cooperation in turn depends upon a conception of political power and legal authority that is objective and informed by the public interest, not personalities, personal relations, or personal interests of individuals elected to serve. The flipside of the collective responsibility of the Cabinet branch of the executive to the legislature is that the Prime Minister must enjoy the confidence of the legislature. The principle of responsibility and the principle of confidence are different ways of expressing the same central idea of legislative accountability upon which rests the claims of semi-presidentialism as a model of good governance. If it is the President’s personal wishes rather than the confidence of the legislature that determines the Prime Minister, then the assumption on which the model is built collapses. It is then not semi-presidentialism but monarchical presidentialism.

It would be clear to the reader from this how President Sirisena’s actions in the fortnight since 26thOctober have not merely violated discrete textual provisions of the Constitution, but also upended the underlying conceptual basis on which our system of democratic governance is built. While semi-presidentialism remains the structure of government that the 1978 Constitution established, President Sirisena’s predecessors have, like him, fiddled with it for undemocratic ends. President Jayewardene tampered with the principle of the fixed presidential term by the Third Amendment in 1982 when it allowed the incumbent to alter the timing of his re-election. President Rajapaksa’s Eighteenth Amendment in 2010 was a much more violent and pernicious attack on the conceptual framework of semi-presidentialism when it, among other things, abolished the two-term limit altogether, and moved Sri Lanka in the direction of the populist, authoritarian, and monarchical presidential states of Africa, Latin America, and Central Asia. In 2015, the Sri Lankan people decisively rejected this trajectory of constitutional development, and mandated the Nineteenth Amendment which cured the defects created by both the Third and Eighteenth Amendments by restoring the fixed-term principle, and thereby returning the 1978 Constitution to consistency with the classical model of semi-presidentialism.

The Fixed-Term Parliaments Principle

The Nineteenth Amendment was driven by the democratising impetus of the January 2015 presidential election, where the mandate for good governance and the reform or abolition of the executive presidential system was delivered as a result of the people’s disgust with the excesses of the Rajapaksa regime. One of the ways in which the Nineteenth Amendment delivered reform in this respect was by reducing the terms of both President and Parliament from six to five years, and by reintroducing the principle of fixed terms into the Constitution. We are concerned here with only Parliament, and we have seen above the provisions of Article 70(1) which give effect to this principle. For all but the last six months of its five-year term, Parliament is protected from acts of unilateral presidential dissolution, although Parliament may be earlier dissolved when Parliament itself requests it.

The principle of fixed parliamentary terms is widely reflected in modern constitutions, with even the United Kingdom, the home of the Westminster system which is often thought of as being inconsistent with the notion of fixed-term Parliaments, having adopted it in 2010. It is found in most European countries, and in most Commonwealth countries in both central and sub-state legislatures except New Zealand and the Australian federal Parliament. There are many benefits to fixed-term legislatures. First and foremost, it restricts the power of the executive, and gives Parliament a coeval role in the constitutional relationship between executive and legislature. Secondly, it reduces the political advantage of the ruling party in the timing of elections, by fixing this in law than leaving it to the discretion of the incumbent government, and for the same reason, thirdly, it alleviates executive dominance of the legislature. Fourthly, it clarifies the rules of government-formation and duration in office by simplifying the term of Parliament, and the contrast between the straightforward Article 70 after the Nineteenth Amendment and the more complicated Article 70 before it is a good example of this. For all these reasons, and seen against political needs of democratisation in Sri Lanka, the fixed-term Parliaments principle is one of the best and most useful innovations introduced by the Nineteenth Amendment, and it must be robustly defended by anyone committed to the 2015 agenda of good governance.

Unmindful of these major constitutional benefits that have persuaded the majority of modern democracies to adopt the principle, some contributors to the current debate have tried to make out that the fixed-term Parliaments principle is undemocratic, because it prevents – or more accurately, makes more difficult – the ability to dissolve Parliament and call a general election in the middle of a parliamentary term. It is supposed to negate popular sovereignty by placing obstacles in the way of a quick resort to elections. Some have even attempted disingenuous analyses of the old Article 70 as an embodiment of the traditions of parliamentary democracy, replete with nostalgic references to the Independence and First Republican Constitutions. Conspicuous by its absence in these analyses is the fact that in Westminster systems, the Head of State alwaysacts on the advice of the Prime Minister – a proposal in the original Nineteenth Amendment Bill that was fought tooth and nail by the same people now making hypocritical allusions to parliamentary democracy. This type of analysis is misleading for a number of reasons. Firstly, such arguments are being made not because of a commitment to parliamentary democracy or the Westminster model, but in order to provide political cover to the illegal and unconstitutional actions of the President on 9thNovember, and to undermine those who are criticising these actions by insincere appeals to the legacy of the pre-1978 past. This is a clever exploitation of the popular misconception that authoritarianism began with the 1978 presidential Constitution.

Similarly, the popular sovereignty argument is duplicitous, or at best, superficial. Resorting to elections in order to bypass constitutional accountability to Parliament is not democratic, but in fact categorically anti-democratic and contra-constitutional. Its aim is not to further popular sovereignty as is claimed, but to unleash the exercise of naked power from any civilised legal regulation. Its aim is to legitimise illegal and unconstitutional actions that fall foul of the procedures established by the Constitution for smooth institutional relations between the executive and the legislature. If an early election is required, then there is a procedure in the Constitution to be followed, which I described above. There cannot be elections outside of the relevant constitutional and legal framework. Bypassing the accountability to Parliament and appealing directly to the people are also classically populist methods, associated in history with leaders such as Napoleon, Mussolini, and Hitler. This kind of argument has no place in a modern constitutional democracy and it is a clear acknowledgement of their utter desperation that supporters of the President’s actions are resorting to it, when their other tactics to bolster an illegal transfer of power have backfired.

Most if not all of the actions taken by the President since the constitutional crisis began on 26 October 2018 have been politically unethical, contrary to the letter and spirit of the Constitution, or outright illegal. His purported dismissal of the Prime Minister who enjoyed the confidence of Parliament is contrary to the clear provisions of the Constitution, despite regrettable attempts to mislead the public discussion by some lawyers and commentators. His subsequent prorogation of Parliament was an attempt to suppress the democratically elected institution that is the expression of the people’s legislative sovereignty, and to evade accountability. The prorogation was made in order to induce crossovers through illegal and illegitimate means, so that a majority could be manufactured to support his illegally appointed Prime Minister. Suppressing Parliament in this way means that the President is trying to thwart the sovereign will of the people, as democratically expressed in the last general elections. When that attempt clearly failed, the President has purported to dissolve Parliament in clear violation of the Constitution.

In regard to every one of these acts, the Constitution lays down the procedures through which the President could have acted lawfully, but he has chosen to act in violation of the Constitution instead. No appeal to the people through a general election can legitimise nor render legal his fragrantly illegitimate and illegal actions. They are, rather, a desecration of the values of the constitutional democracy built on popular sovereignty that is established by the Constitution. Popular sovereignty means that government is conducted according to the democratically expressed wishes of the people. What the President and his collaborators in this constitutional crisis have done is to usurp popular sovereignty, replacing it with a false ‘sovereignty’ of the executive presidency.

To attack the principle of fixed-term Parliaments as undemocratic in this context is simply – and not very effectively – to proffer a fig leaf for presidential authoritarianism and lawless political conduct. Such attempts must be dismissed with the contempt that they deserve.

Conclusion

In one of only three democratising amendments to the 1978 Constitution (the others being the Thirteenth and Seventeenth Amendments), the Nineteenth Amendment was the result of a remarkable democratic mandate. It is by no means perfect, and it could have gone much further, but it established some important principles for the regulation of the political power that had been given unbridled freedom previously, especially under the Eighteenth Amendment. The constitutional coup of 26thOctober has imperilled this positive trajectory of constitutional development. In particular, the completely illegal dissolution of Parliament on 9thNovember has trampled on the crucial principle of fixed-term Parliaments. It must surely be the hope of every right-thinking Sri Lankan citizen that the Supreme Court, once seized of the matter, will act to boldly and swiftly arrest the threat of democratic decline.