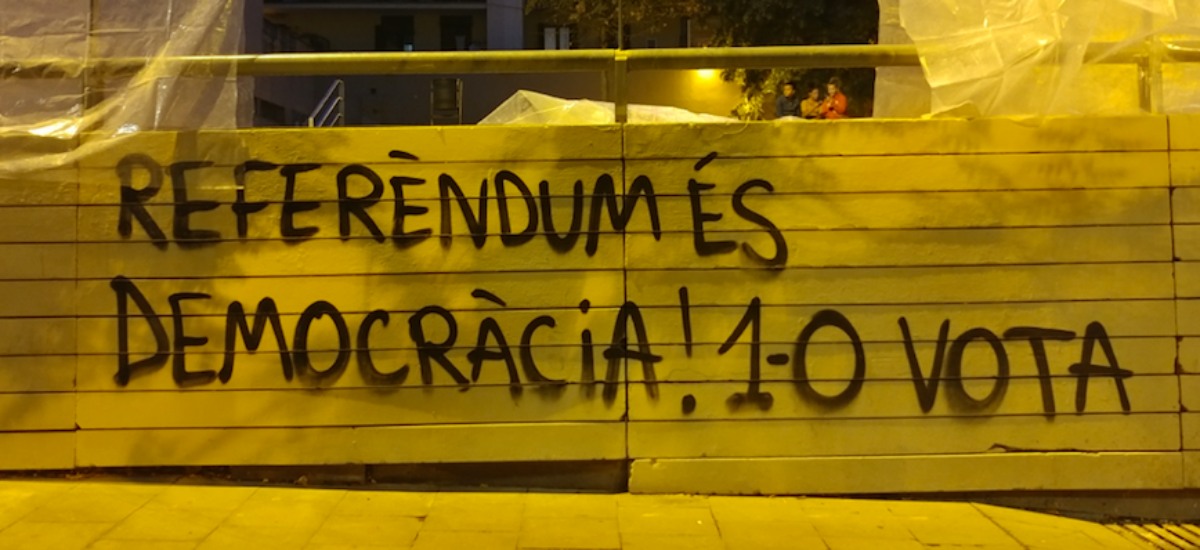

Featured image courtesy the author – A slogan written by ‘night commandos’, “Referendum is democracy. Vote 1st October”

Background of the Catalan Referendum

On 28th June 2010, the Supreme Court of Spain rejected the Catalan Statute of Autonomy, modified and approved by both the Catalan and Spanish parliaments in 2006. An application of the updated Catalan Statute was viewed as the most novel departure of the Spanish democracy since the end of the Francoist dictatorship, as it recognised broader competences for the Catalan government and, above all things, the Catalan people as a nation. Two weeks after the Supreme Court’s verdict, more than a million people of Catalonia went out into the street, under the slogan of ‘We are a nation’ (Sóm una nació), to protest the Court’s decision. Since then, local grassroots movements for independence have continued to grow.

The referendum for Catalan self-determination that took place on 1st October 2017 was the culmination of this process. Many Catalan independentists and local grassroots organisations had been pressuring the Catalan president to hold this referendum since 2012. When the Catalan government finally declared that it would do so, however, the Spanish Supreme Court suspended it. As the Catalan government and civil society adhered to the original plan of voting, the Spanish police took forceful measures to block it: they raided local press offices, confiscated voting papers, etc. From the period of the voting campaign until the day of the referendum, the Catalan people had a strong sense of déjà vu about what they had experienced half a century ago: the authoritarian regime under Francisco Franco. I saw their reactions first-hand while I was in Barcelona as an international observer for the referendum.

Making the Referendum Possible: Grassroots Mobilisation and State Intervention

When I arrived in Barcelona on 28th September, the final stage of the referendum campaign was in its full flow. Many street symbols and slogans, which had usually been ones inspired by the Catalan independence flag, were changed and carried more concrete messages, such as ‘yes’ for the winning of the referendum or greetings to the envisioned Republic of Catalonia. Many stores used their show windows not only to demonstrate new products for winter, but also to be explicit about their support for the referendum. This was a big change compared to the last couple of years when shopkeepers were in general reluctant to display any independentist material in their shops for fear of a loss of clients. Pointing to referendum promotion materials on his cashier’s desk, a man running an organic farmers’ market in the neighbourhood of Gràcia said, ‘After having seen what the Spanish state did to us in these days, being quiet doesn’t make sense anymore’.

As this man asserted, what the Catalan people experienced during the period of the referendum campaign insinuated a total emotional break-up with the Spanish state. Although many international media have been focusing on the Spanish violence which was manifested on the day of the referendum, a state intervention had started long before, and the Catalan citizens’ experience of the ‘anomaly’ lasted during all of September. When the Catalan referendum campaign was officially launched by the Catalan government, it was illegalised by the Spanish Supreme Court, and an official webpage promoting the referendum was shut down constantly. Every time it was blocked, a newly copied one was created based on foreign servers, and it was the Catalan president, Carles Puigdemont, who used Twitter himself to inform the Catalan people of the change of its address. The peak of the Spanish official oppression happened when the Spanish police raided a printer’s shop and regional newspaper offices in search of voting papers. Residents in that town, congregated in front of police blocking the press offices, chanted a mocking song: ‘Where are the papers? Papers, where are they?’ This kind of police intervention and political protest were shaping the everyday lives of Catalan citizens in September 2017.

With these difficulties in developing an official referendum campaign, Catalan citizens mobilised themselves to complement the campaign via grassroots organisations. They telephoned the electorates to inform the nearest polling stations and designed and printed the promotional materials for the referendum. The people who attempted to distribute the materials were the ones who experienced the state control directly. A neighbour of 67 years, from Gràcia, carrying her material in the middle of the day, explained how she had run away from two Spanish policemen when she was asked to show her ID. She stated, ‘I just got on my husband’s moto bicycle, abandoning materials behind. When I say, “this is what you can experience in a fascist regime”, I don’t say that as a metaphor, but it is just the same as Franco’s years. You were stopped to be interrogated’, she continued. For those who lived under the Francoist regime (1936–1975), this kind of experience reminded them of Catalonia in the 1960s, when people were stopped and questioned by the Spanish police. The younger generation had a chance to see how their indirect experience of the past turned into a direct one. Since the start of the referendum campaign, many young people formed a group of three to five, named ‘night commandos’ (commandos nocturns), to glue posters, usually after midnight to evade Spanish police’s surveillance. A 3rd-year university student majoring in communication stressed, ‘We are younger, so we can escape easily when we are caught, but we’re trying to be cautious. At the same time, I feel weird, having this obscure, past-provoking experience. Probably not the past anymore’.

In the middle of a blurry boundary between the past and present, Catalan people gathered their forces from their neighbourhood to make the referendum happen. As polling stations—usually public schools—were expected to be shut down by the Spanish authority, Catalan people organised two-day activities to keep them open. Especially, it was the Association of Mothers and Fathers of Students (Associacions de mares i pares d’alumnes, AMPA) that organised a type of free school, offering activities such as drumming class and Japanese calligraphy sessions for anybody who wanted to participate. On the eve of the referendum, many neighbours supporting the poll brought their camping tents or sleeping bags to stay overnight, thereby keeping the polls open for others.

AMPA running a drumming class with their kids to maintain polling station open

in the neighbourhood of Gràcia (photo: author)

On the Day of the Referendum

Neighbours started to gather around polling stations from 6:30 am in the middle of a heavy drizzle. This early gathering was to prevent, again, the Spanish police’s closing down of the polling stations. Many of them were wearing rain coats and brought fishing chairs for long queuing. They had radios, novels, battery chargers, and coffee in flasks, but speculation was still rampant about what was going on and whether they would really vote or not, as nobody had seen ballot boxes except from a photo on the Internet. When ballot boxes arrived an hour later, wrapped tightly with black plastic bags, people cheered and clapped in delight, shouting, ‘We will vote, we will vote!’ When voting started around 9 o’ clock, the polling station where I was staying in the neighbourhood of Example d’Esquerra was full of people in cheery moods. Taking photos of themselves voting and kissing the ballot box, many voters were delighted to find that they could finally vote. A 98-year-old woman in a wheelchair accompanied by her son held her hand high with her voting paper to much applause. With a bit of emotion, one of the neighbours in charge of the polling station reminded us of how hard the process of voting preparation had been: ‘I never expected voting could be such a difficult thing in a supposedly democratic country. Why should we be worried about consequences for exercising our right to self-determination?’

People waiting for voting outside the polling station (photo: author)

People waiting for voting outside the polling station (photo: author)

However, as the voting process was interrupted constantly for Internet control, the atmosphere became heated. Webpages where constituents’ information was verified and registered were frequently down. The chief members of the polling station had to figure out a different IP address every moment to enable the voting. People had to queue more than an hour without being able to vote due to Internet disconnection. When some images of Spanish police raids at other polling stations started to be circulated through social media, polling members in our place became shaken as well. While voting was going on, they began talking about procedures in case of police attack: Who will stay inside the polling station? Where to hide the ballot boxes? Is it necessary to move whole casted voting papers into one box? Are we obliged to show our IDs if we are asked to by the Spanish police? What fine would be imposed on us? Although the Spanish police didn’t come to our place, members of the polling station passed the whole day under an excess of pressure. ‘I feel like I just got off a roller coaster’, said a member of the polling station with a deep sigh coming out of the building.

Conclusion

In the end, 92% of the participants voted yes for independence. Nevertheless, independence was declared just symbolically without any legal procedures. Currently, eight Catalan politicians and two independence activists are jailed without bail. The Catalan president is staying in Brussels, while the Spanish state urges the Belgium authority to send him back.

From September to October 2017, many people in Catalonia experienced both astonishment and dismay at the lingering vestiges of the Francoist authoritarian regime. Police raids, confiscation of voting papers, violent crackdowns on voters, and imprisonment of Catalan politicians were interpreted as signs of the resurrection of the past, an obscure age. A neighbour from Gràcia who engaged with a student movement against dictatorship in Barcelona during the 60s stressed: ‘We’ve just entered into another tragic period. When I was a student in the 60s, distributing leaflets and running away from the police was my everyday life. I’ve never imagined that I would repeat this experience. I feel tragic’. Another neighbour even described the Spanish state as having a ‘Catalan repression script which can be repeated every fifty years’. No matter how the situation evolves in the future, it seems that the resumption of dialogue between Spain and Catalonia would be impossible, as the Spanish state summoned the spectre of the authoritarian past. In doing so, Spain’s new departure to democracy became a failed project, and it downgraded all the social values established since its transition to democracy. Those who cannot get over the past will never be able to write a new history.

Editpr’s Note: Also read “A federal Spain in a federal Europe“