“The national identity scheme represents the worst of government” said Theresa May, the then UK Home Minister. introducing a bill to scrap the national biometric ID scheme in the UK . “It is intrusive and bullying, ineffective and expensive. It is an assault on individual liberty which does not promise a greater good.” Mrs May’s record on civil liberties may be mixed, but in 2010 when the conservative-led government came into power, scrapping of the UK’s national ID scheme was one if it’s first order of business. Thus ended a robust debate over the national ID in Britain.

The scheme pitted the usual political foes and drew opposition from civil society groups and academia. The opponents argued the national ID threatens to fundamentally alter the relationship between the citizen and the State, an argument that ultimately held sway. The scheme lasted less than five years.

Unlike in the UK, Sri Lankans have long accepted their status with the State as some sort of gentrified cattle. Introduction of a digital National Identity card — the e-NIC — doesn’t seem to significantly alter this relationship, even if this new scheme includes fingerprints, iris scans and other biometrics as well as a central database.

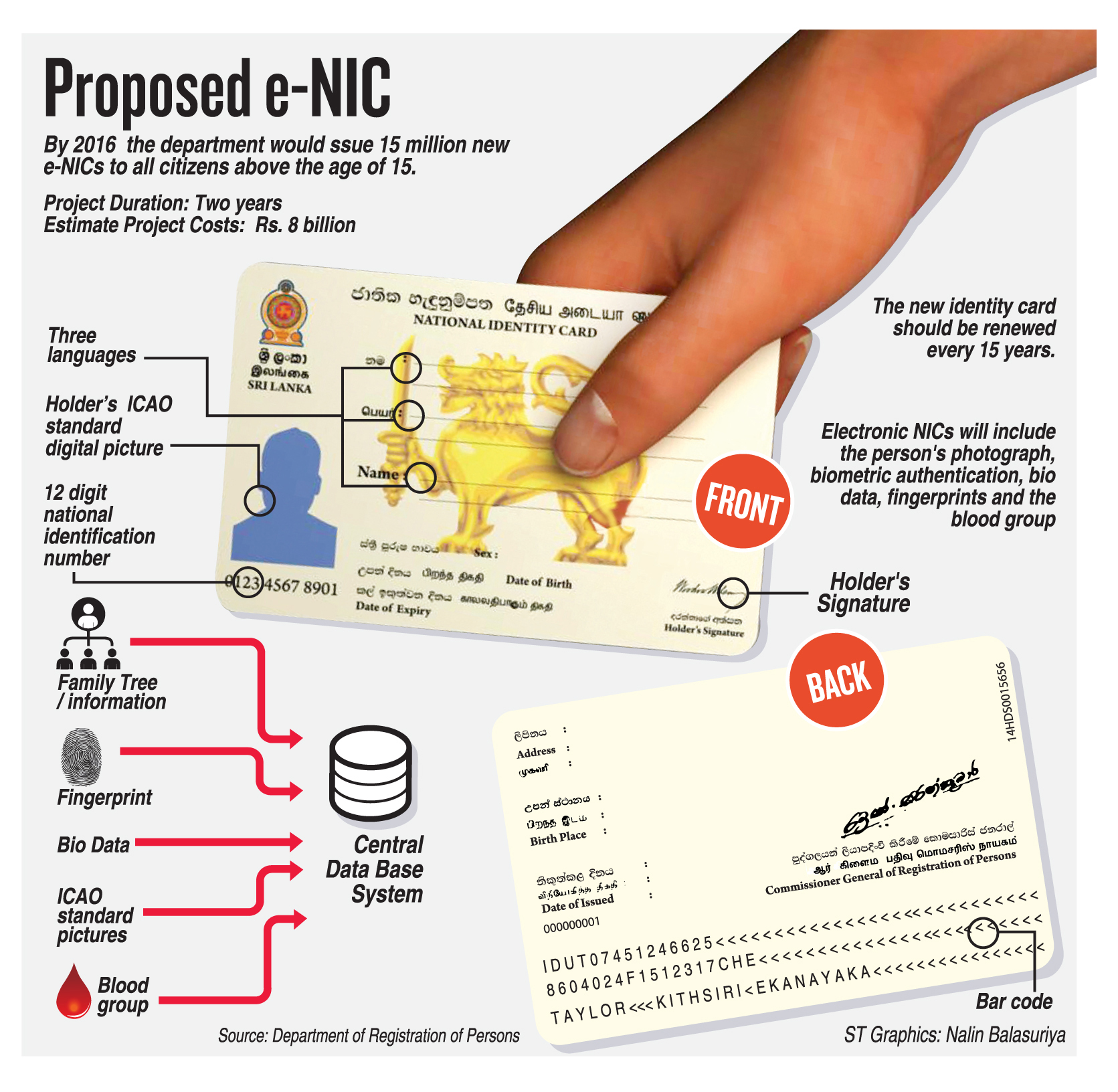

This is perhaps why that last week, when Minister of Internal Affairs S.B. Nawinna introduced the regulations for the soon-to-be-rolled out e-NIC, there was barely a whimper of opposition. Not from the mainstream media or civil society groups. Not from government’s own champions of civil liberties nor the joint opposition. The event itself was a rather boring affair. The minister insisted that the current national ID is unsuitable for the times and the new e-NIC with its biometric and ‘family tree’ data would improve efficiency of service delivery in government, ensure national security and contribute towards speeding up of economic development.

At first glance, the Minister’s remarks makes sense. The NIC that most of us carry around is based on ancient technology — a laminated card with a picture and some handwritten details. That interacting with the state day to day is painful is a fact of life that most Sri Lankans have come to accept. To prove one’s identity and related details, requires plenty of paperwork, filling lots of forms and going physically to a myriad different places. This is hardly the way we should be doing business two decades into the 21st century.

Image courtesy The Sunday Times

The e-NIC, we are told, is destined to change all that. In one incarnation, the e-NIC is part of the Household Transfer Management (HTM) System, where Samurdhi and other subsidy recipients will get their monies efficiently, preventing leakages and corruption. In another use case, it is expected to make tax collection easier, be the backbone of a National Payment Platform (NPP) and make mundane things like opening bank accounts painless. If you listen to proponents, e-NIC is the key to a to new Digital Sri Lanka with seamless service delivery enabled by merely your fingerprints and a centralized database of identity information.

If all that sounds too good to be true, it probably is.

There are a number of reasons to be skeptical. First, most software systems in Sri Lanka including various government databases have long used the NIC number as a unique key in their databases. If improving service delivery is the goal, merely digitizing existing government data and establishing a protocol of sharing that information should be enough to bring about most conveniences. You do not need biometrics or additional information not present in your current NIC to make that happen.

Indeed many countries that have enabled high levels of digital service delivery have done so without a national database and biometrics. Where biometrics do exist currently — in my driving license for instance — it has failed to significantly improve the citizen experience. The necessity of a biometric digital ID forms much smaller part of creating acceptable levels of digital service delivery than its proponents have you believe.

Quite apart from biometrics, there are the inherent risks of holding the nation’s entire identity information in a central database that is accessed by various government — and possibly private — entities. The system immediately becomes a magnet for hackers. In the age of cyberwarfare and the usual sloppiness with which information security is treated by those in the Sri Lankan government, this should be a serious concern.

As a whole, the system opens itself up to all sorts of abuse by errant individuals or organized groups. Having access to people’s linked data on all activities the person has with the state, their family and perhaps bank details is a worrying amount of information that could be at few people’s disposal.

The e-NIC scheme is also easily converted into a system of mass surveillance that can be used to target dissidents, political opponents and others. All it requires is the right political moment and the wrong people in power. This needless to say is an enduring risk in Sri Lanka. Indeed the genesis of the e-NIC project lies in the national security state mentality of the conflict-era that has simply got a rebranding as a service efficiency project under the ‘Yahapalanaya’.

None of this is theoretical. In Pakistan, the NADRA database that enables the country’s national digital ID has gone through multiple hack attacks some of it apparently successful. The program has also seen what can only be described as surveillance state innovation. The Pakistan Police now has NADRA enabled apps including ‘Hotel Eye’ – which tracks hotels and their guests, and so called ‘predictive crime software’ that upon entering the Digital ID pulls out data such as family tree, ATM cards, call data, hotel bookings and location information.

Pakistan’s NADRA was the chosen supplier for Sri Lanka’s e-NIC scheme and completed the first phase of the project, before the present government called in for fresh tenders for phase two of the project.

India’s Aadhar scheme — the largest biometric digital ID project in the world — is more measured. Yet there have been widespread reports of misuse and exclusion. Tall tales of millions of rupees of savings from plugging welfare leakages — a key argument for the introduction of Aadhar — remains unsubstantiated. As the ambit of Aadhaar expands, some its earlier proponents have turned critics. Last week, the Indian Supreme Court threw new a spanner in the works by declaring the right to privacy to be a fundamental right, which some argue makes the current implementation of Aadhar untenable.

In Sri Lanka, It is the inadequacies of privacy and data protection laws that makes abuse even more likely. To be fair, many of the privacy issues pre-dates and exists independently of the e-NIC project. There is no doubt that digitization of data in both private and public sectors will have to face up issues around privacy, data protection and information security. But the e-NIC makes matters particularly urgent.

For one, the e-NIC enabling legislation leaves open wide gaps that can be exploited to create a system of mass surveillance. The law allows the state to collect biometrics, family and unspecified ‘other’ information about citizens and store them in a central database called the “National Register of Persons” (NRP). It also allows authorized persons to access this data on grounds of national security, ‘crime detection and prevention’ and doesn’t specify a clearcut consent architecture.

For all it’s faults, non-digitization and the ‘dumb NIC’ in our pockets safeguarded a valuable principle of citizen initiated identity verification. When you want to establish you are who claim you are, you produce the ID which is then verified against how you look. While imperfect, this preserved a measure of privacy and its own de facto consent architecture. With the e-NIC it makes it possible to perform “Card not Present’ data access and verification requests without the person’s explicit consent.

All of this is compounded by the fact that unlike in India, or Britain where there was a widespread debate on the surrounding issues, in Sri Lanka the biometric digital ID project is being carried out almost in indifference. Apart from a few op-eds scattered throughout the last 12 months or so, most Sri Lankans have been either unwilling or too unaware to engage on the issue.

It is partly due to the pressure from civic groups, the managing authority of Aadhar in India had to release copious amount of information, attend parliamentary hearings, release APIs and technical documentation. Sri Lanka’s DRP however can get away with a single outdated web page on the project.

This means we still do not know the technical architecture of the e-NIC. How the data is stored, secured, shared and governed. We do not know who’s allowed to access the data or how privacy of individuals are protected and what safeguards we have to prevent surveillance of persons.

This is unacceptable.

Then there are the larger policy questions. Does the e-NIC pass the cost-benefit test? We do not know because unlike in India’s Aadhar, benefits have not been articulated or hard numbers presented. What model of privacy should Sri Lankans accept? Is it the the China model of ‘running naked’ to the state? Or one that emphasize individual privacy or somewhere in between? How much privacy do we have to sacrifice to gain acceptable levels of service delivery and national security? What laws need to be in place to address the challenges posed by technology adoption and digitization?

Some of these will have multiple complicated answers. Compromises will have to be made. But we should find a way to realize the promise of digital transformation in government and preserve personal liberty. How do we go about it? Our current silence on e-NIC would not help us find answers.

The writer has a day job in technology and an interest in public policy.