Featured image courtesy Women and Media Collective

Sri Lanka was ushered into Independence under the Soulbury Constitution in 1948, followed by the Constitution of 1972, making the current Constitution, the second Republican Constitution of Independent Sri Lanka. The Soulbury Constitution, the 1972 Constitution, the 1978 Constitution and the Draft Constitution of 2000 followed the same tangent of being based on ethnic prioritisation and division with no other underlying principle or core values governing them. Despite the Soulbury Constitution being widely speculated to be progressive and fair to minorities, the current constitution and the 19 amendments that followed it have not been able to maintain the same progressive approach. As such, this document has earned widespread criticism and even evolved as a premise that led to an ethnic war that spanned over three decades.

These factors, among others, contributed to a warm welcome extended towards the 15th Parliament established by the coalition of the two major parties in Sri Lanka who came in with the promise of a representative and progressive Constitution. The coalition government elected as a result of the efforts of the social movement led by figures such as the late Ven. Sobitha Thera, with the contribution of civil society actors, unions and a society that yearned for freedom from an authoritarian regime.

However, the political will or lack thereof of the coalition Government was miscalculated by the majority who elected them. The symptoms of the lack of will were apparent when matters pertaining to formulating a new Constitution were not prioritised and assigned to fall under a Ministry by the two successive cabinets that were appointed. This oversight continues to reflect on the lack of will and consistency of the Constitution making process. The conflicting statements made by various representatives of the Government could be fairly attributed to the lack of a unitary body with sufficient authority vested upon them that is overseeing the process.

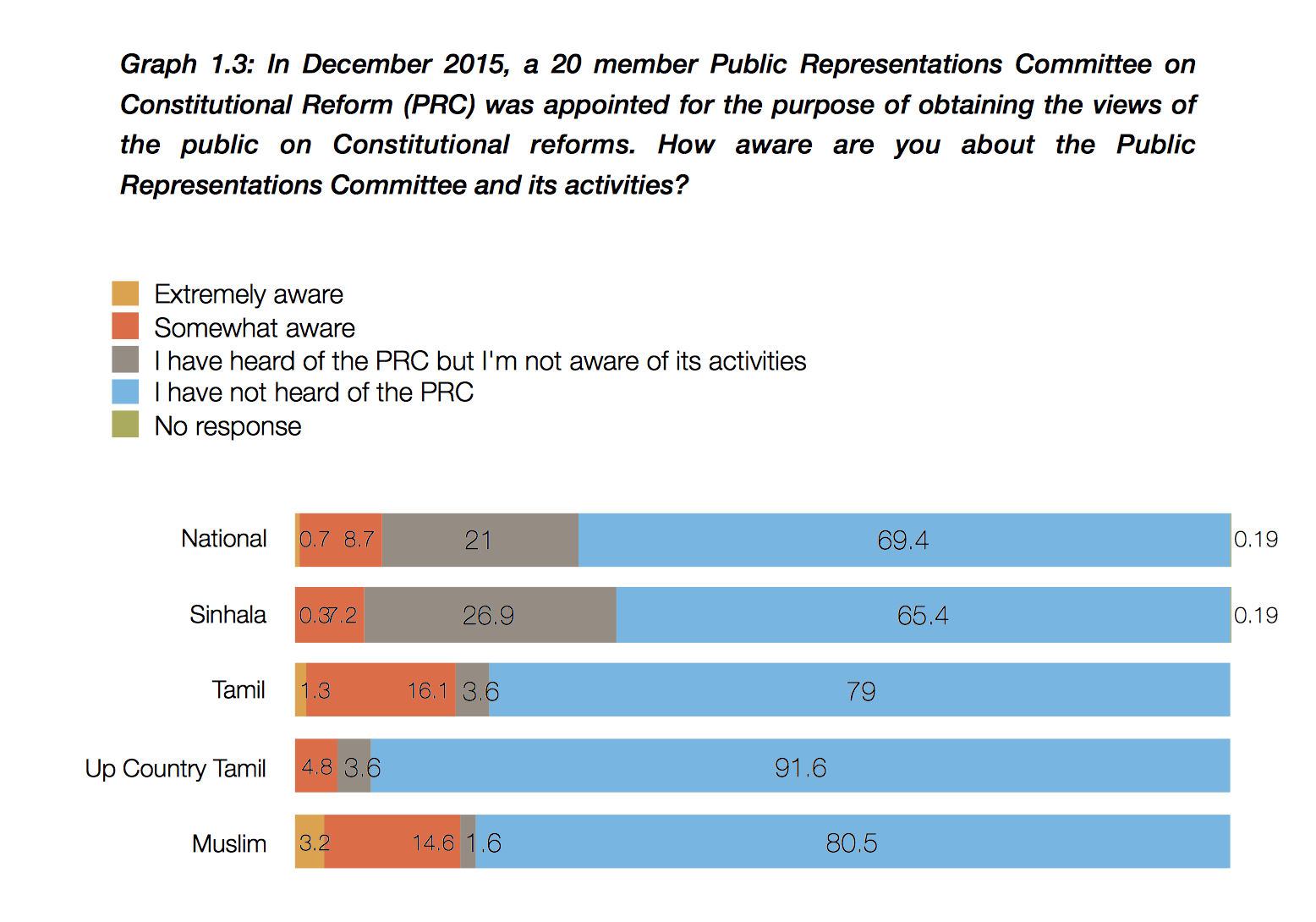

The lack of consistency has led to a general public that are either unaware or, worse yet, misinformed on the seemingly uncoordinated efforts of the Government. Information pertaining to the concept of a new Constitution and the process that leads up to it have not been instilled among the general public resulting in citizens that are rapidly losing interest and confidence in the Government and the process as a whole. This was particularly true in the haphazard process that the Public Representations Committee on Constitutional Reforms conducted public consultations. Even though the limited scope of the Report was attributed to the lack of time and resources for consultations that went beyond what was accomplished, the process still reflected the lack of political will and commitment to the matter on part of the Government. The Sub Committee reports that were subsequently compiled also go on to reflect the same lack of representation. This reiterates the single greatest flaw in the on-going process; limited public participation due to the lack of awareness among the general public. Further attesting this, the ‘Opinion Poll on Constitutional Reforms’ (2016) conducted by the Social Indicator unit of the Centre for Policy Alternatives reflects the general displeasure of the public, particularly on the Government’s degree of communication.

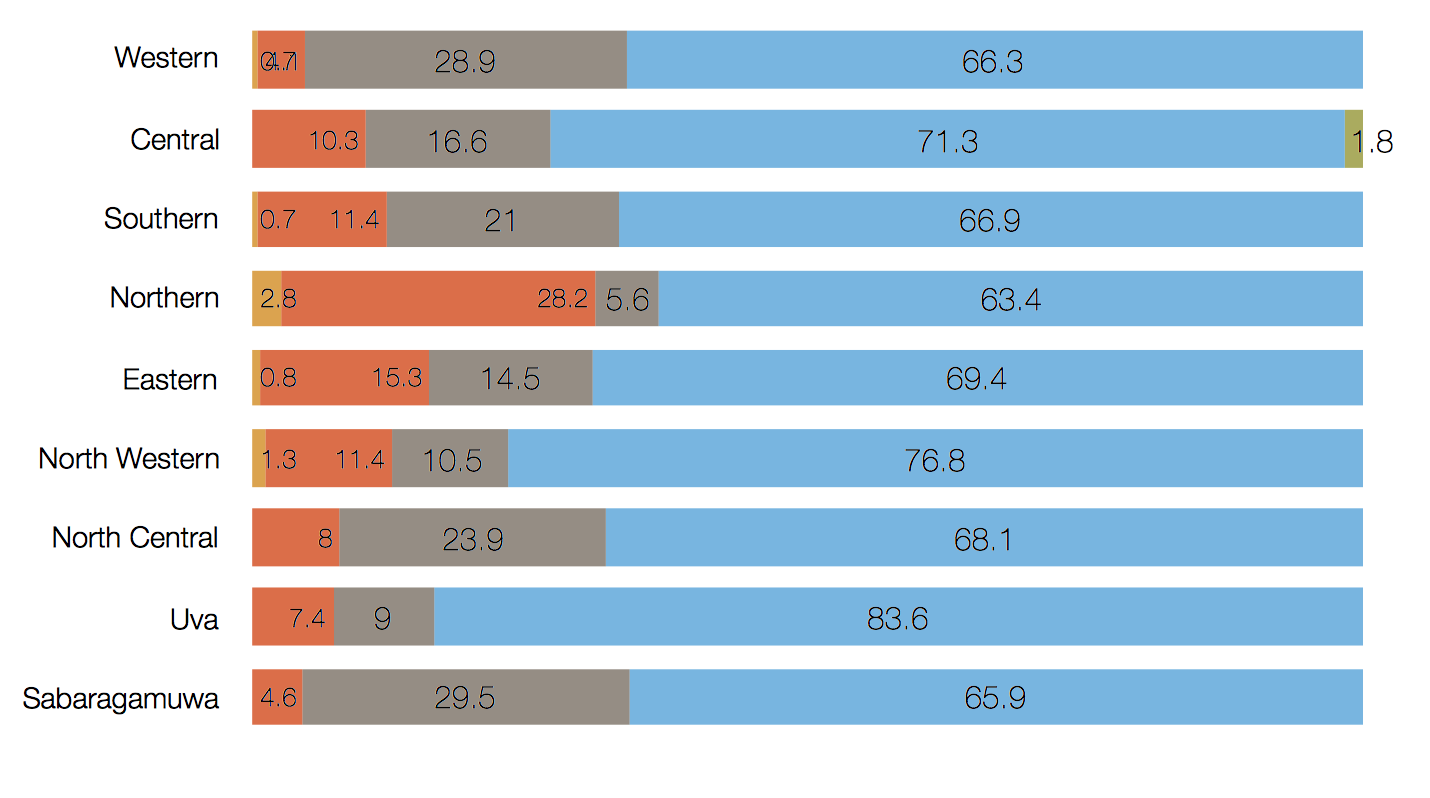

Figure 1: Extract from the Opinion Poll on Constitutional Reforms conducted by the Social Indicator Unit of the Centre for Policy Alternatives (October, 2016).

Figure 2: Extract from the Opinion Poll on Constitutional Reforms conducted by the Social Indicator Unit of the Centre for Policy Alternatives (October, 2016).

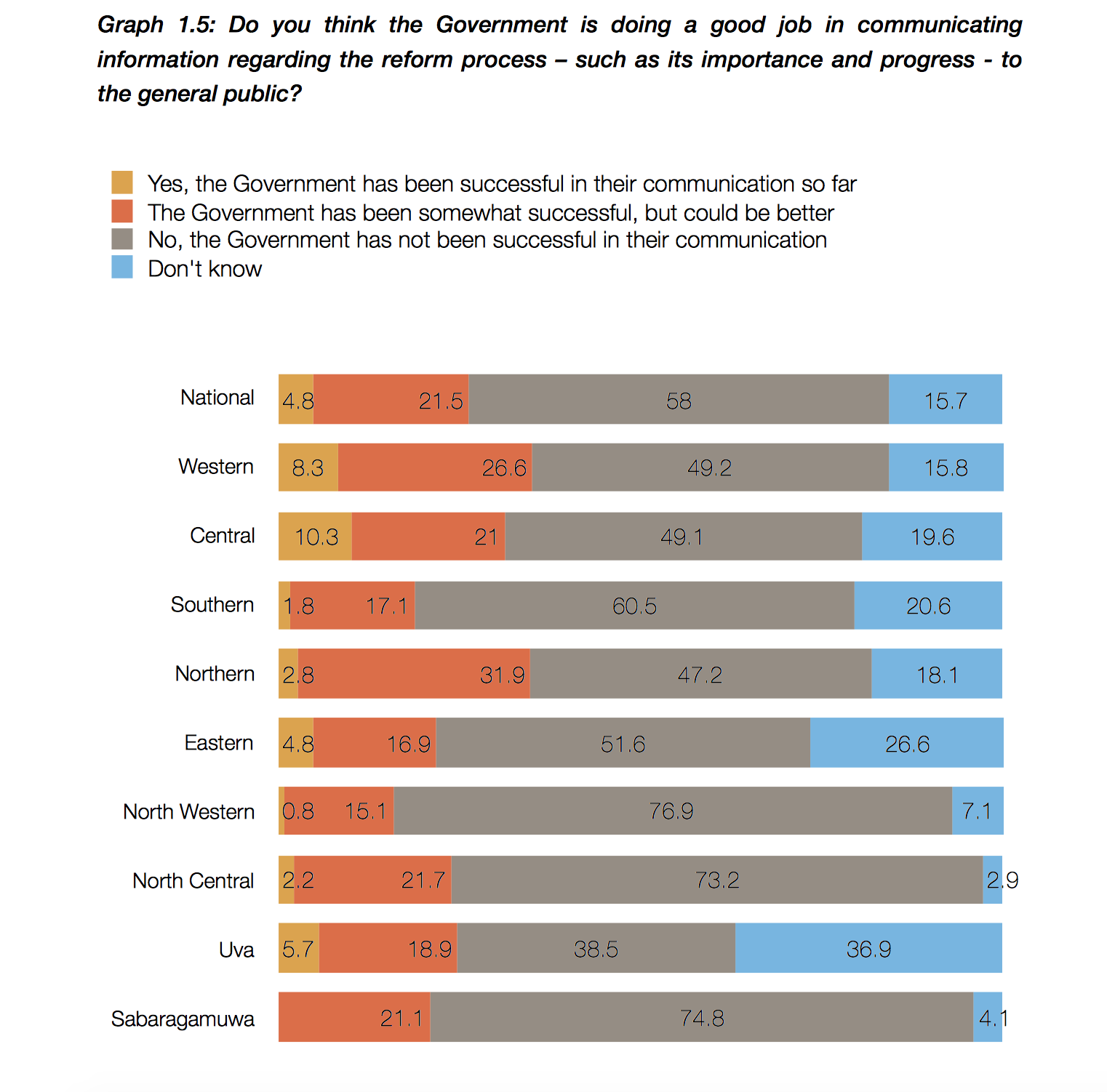

Figure 2: Extract from the Opinion Poll on Constitutional Reforms conducted by the Social Indicator Unit of the Centre for Policy Alternatives (October, 2016).

This inconsistency and lack of transparency that manifests itself as political turbulence has inadvertently provided a platform to those who oppose Constitutional Reform. Needless to say, the parliament is more polarised on Constitutional Reforms than on just about any other issue that they have tackled through their time in office. Those who are at the opposing end of the spectrum have taken the opportunity provided by the Government through their detached conduct to inculcate misinformation regarding certain provisions that are suggested. For instances, voices of those such as Ven. Athuraliye Ratana are now taking the forefront with extremist views regarding devolution of power. The absence of facts disputing these claims provided by the Government as they should have led masses to believe in the only facts their presented with. This has resulted in the general public embracing the idea that New Constitution is a separatist agenda and biased towards ethnic minorities, among other reigning misconceptions. The continued silence, incoherency and overall complacency of the Government adds to the growing confusion and misconception among the general public. As a government that intends to submit the New Constitution to the public in the form of a referendum one would hope they would be more proactive in engaging the public and disputing misinformation as the process evolves.

Figure 3: Extract from the Opinion Poll on Constitutional Reforms conducted by the Social Indicator Unit of the Centre for Policy Alternatives (October, 2016).

Figure 3: Extract from the Opinion Poll on Constitutional Reforms conducted by the Social Indicator Unit of the Centre for Policy Alternatives (October, 2016).

However, it is imperative that a new Constitution is laid out as the Supreme Law of the state. The process of reconciliation and a solution to the ethnic conflict will only arise from sustainable changes that could be brought about by a new and inclusive Constitution. As such, the importance of salvaging the process leading to its creation is indisputable. The way forward should entail a strategic and transparent awareness campaign, deploying significant amounts of resources such as state media, both print and electronic, for this purpose. It is also imperative that matters such as constitutional reform and an awareness of civic responsibility is instilled among the younger generation through reform in the education curriculum. It is important that the future leaders of the country are aware of their civic responsibility and more vigilant and proactive in matters such as constitutional reform.

Furthermore, the government should arrive at consensus regarding key debates such as abolishing the Executive Presidency and the 13th Amendment, and make their stance in this regard clear to the general public, accompanied with sufficient justification for why said decision was made. In doing so, the government also needs to acknowledge and to a certain extent accept the Draft Constitution of 2000 as a basis upon which the new Constitution is modelled on. Especially considering the time constraints and the urgent need for a new Constitution, the government should draw from the Draft Constitution if they are to accomplish sustainable solutions. The government must take concrete measures to engage the general public while also recognising the willingness of the Tamil National Alliance and other major parties that were previously divided based on ideological differences, to come together and proceed with crafting a New Constitution in order to provide sustainable political solutions for the ethnic problem.

As the Centre for Policy Alternatives, we stepped in as a partner for the ‘Citizens Initiative for Constitutional Change’; a coalition of civil society organisations and individuals dedicated to ensuring that Sri Lanka finally receives a Constitution in 2016. The Citizens Initiative travelled across Sri Lanka and conducted numerous workshops to gauge the opinion of everyday citizens and what they believe must be included in a new Constitution. In addition, an email and letter campaign reached thousands of people; which resulted in a myriad of suggestions, confirming people’s interest and enthusiasm for this cause. Furthermore, following the release of the PRC Report and the subsequent release of six Subcommittee Reports, discussions were held with relevant stakeholders from the Civil Society as well as at a Provincial Council Level.

While we will continue to engage in awareness raising and ensuring public representation as a civil society actor, the Government must be more proactive in addressing these concerns themselves without further ado. It is imperative that the Government realise that they are at the pinnacle of political opportunity as the majority of political parties and key influencers have come together with the common agenda of creating a new constitution. This realisation must be coupled with the awareness that prolonged inconsistency will result in losing public trust, at which point the government may not be able to sustain the power vested in them by the general public. It is time the Government stops being oblivious to this reality and strategically approaches the situation going forward.

Those who enjoyed this article might find “Achieving durable reform in Sri Lanka” and “Beyond Serendipity” enlightening reads.