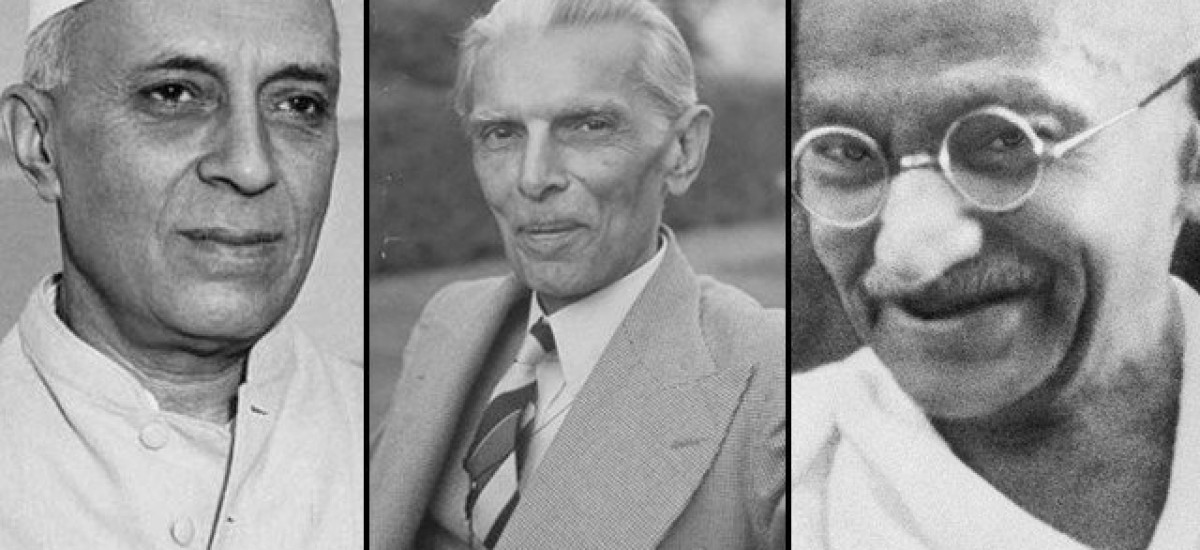

Photo via The Express Tribune

Markandey Katju, quondam Justice of the Supreme Court of India, is a man who does not mince his words. A maverick, he has a penchant for courting controversies. Not long ago, he dubbed Mahatma Gandhi ‘a British agent’ (he also called Subhash Chandra Bose ‘a Japanese agent’). Katju accused Gandhi of serving the imperial agenda and declared as a myth the widely held claim that Gandhi won India her freedom.

For about twenty years Gandhi practised law in South Africa and in 1915 went back to India, where he became involved in the country’s independence movement. In India, he set out to build a mass political movement by injecting religion into politics, thereby exploiting the deeply held religious sentiments of the people. In almost every meeting he participated, he propagated Hindu religious ideas. The Congress was converted to a party of the Hindu masses, leading to the Muslims and the Congress becoming polarised. Citing the eminent jurist Seervai in support, Katju has argued that Gandhi’s method of appealing to Hindu ideas inevitably led to partition.

Had Katju been in Solon’s Athens, where speaking ill of the dead was prohibited by Solon’s law, his remarks would have got him into hot waters. In twenty first century India, Katju’s remarks touched a raw nerve of the law makers because he had spoken ill of the Father of the Nation. Parliamentarians in both houses took the unusual step of passing unanimous resolutions deploring Katju’s comments. The Lok Sabha resolution condemning Katju’s statement reads:

“Father of the Nation Gandhiji and Netaji Shri Subhash Chandra Bose both are venerated by the entire country. The contribution of these two great personalities and their dedication is unparalleled. The statement given by former Judge of the Supreme Court and former Chairman of Press Council of India Shri Markandey Katju is deplorable. This House unequivocally condemns the statement given by former Judge of Supreme Court Shri Markandey Katju unanimously.”

Katju has petitioned the Supreme Court to judicially review the resolutions because they are damaging to his reputation and they condemn him without giving him a hearing. He claims that they undermine his constitutional right to freedom of speech and expression. His contention is that the parliamentary rules of procedure do not contemplate the passing of a resolution against a private person and privilege does not attach to the resolutions. The case is yet to be decided.

The Great Game

To many, it might not seem cricket for Justice Katju to criticise an icon of a nation, where Sachin Tendulkar is deified by many. In a cricket-mad country where the game has become a religion and its followers treat their heroes as demi-gods, one is inclined to the thought that the consequences to Justice Katju would have been far more serious had he tried to bring Sachin a notch down from his high pedestal.

Gandhi showed no interest in cricket. Even before he became a law student, Ranjitsinhji, the Jam Sahib of Nawanagar, who was hailed as the supreme exponent of the game, was showing off his stroke play in the playing fields of Old Blighty. The Jam Sahib might have been the prince of a little state but he was the King of a great game. Neville Cardus referred to him as ‘the Midsummer night’s dream of cricket’ and as ‘a light of the East’. When, in 1932, calls were made for his nephew Duleepsinhji to lead the Indian team touring England, Ranji had said: “Duleep and I are English cricketers!” According to Ramachandra Guha, historian and self-confessed cricket nut, Gandhi had carried with him a letter of introduction to the prince when he travelled to England to study law.

Gandhi apparently had little interest in sport generally, and actively disparaged it. To Gandhi: “The idea that, if our boys and youths do not have football, cricket and other games, their life should become too drab is completely erroneous. The sons of our peasants never get a chance to play cricket, but there is no dearth of joy or innocent zest in their life.”

Gandhi’s reply to a request for a message of support for the Indian Olympic Hockey team is revealing. “You can have no knowledge of my amazing dullness and ignorance. You will be surprised to know that I do not know what really the game of hockey is.” For good measure he added: “I have never attended cricket matches and only once took a bat and a cricket ball in my hands and that was under compulsion from the head master of the High School where I was studying, and this was 45 years ago.”

The holy ghost

In India, where millions worship the cow, Gandhi is a sacred cow and is assigned a special status in the pantheon of freedom fighters. Gandhi together with Motilal Nehru and Jawaharlal Nehru are regarded as the holy trinity of the Indian independence movement, with Motilal the father, Jawaharlal the son and Gandhi the holy-ghost.

After his return to India, Gandhi shed the Englishman’s attire for the dhoti, otherwise known as the loin cloth, and his shoes for the chappals. In his prayers, Gandhi sang the Cardinal Newman hymn ‘Lead, Kindly Light’ and limelight followed Gandhi’s footsteps wherever he went. Jinnah, his political adversary, was by reputation one of the best dressed men in the British Empire whereas Gandhi was one of the worst dressed.

Churchill referred to him as ‘that half naked fakir’. While in London, Gandhi paid a visit to the Palace to meet the royalty, when someone rather unkindly commented on his scanty dress but, not one to be put off, with a twinkle in his eye he responded: ‘The King had enough on for us both.’

Next to the Taj Mahal, Gandhi was India’s greatest ever advert. The splendour of Taj Mahal could inspire an observer to exclaim in its presence, as Plutarch had done when he gazed at the Acropolis: “It is dressed in the majesty of centuries!” In D.B. Dhanapala’s words, the Taj in the moonlight would have been a better sight to behold than Gandhi in his loin cloth!

Dhanapala, a master of the telling phrase, described Gandhi’s pen to a hen that laid slogans as if they were eggs. Swaraj, Ram Raj, Satyagraha, Ahimsa, and Harijan were some of the eggs that Gandhi laid. According to Katju, they were probably hatched even before he had laid them.

Gandhi could produce a telling phrase with which to scotch an idea, as he did by describing the Stafford Cripp’s offer of independence after the war as a ‘post-dated cheque on a failing bank’. The words “on a failing bank” were added later probably by another Jam Sahib. Gandhi dismissively condemned Katherine Mayo’s book ‘Mother India’ as “a drain inspector’s report”.

Gandhi’s Gurjar Sabha speech

It is apparent from Justice Katju’s remarks that Gandhi has his detractors. A prominent historian of India once told me that he never added the suffix “ji” when he mentioned Gandhi’s name. In 1920, Jinnah was booed off the Congress stage by Gandhi’s supporters when he addressed Gandhi as ‘Mr Gandhi’ as Jinnah always did. Gandhi made no move to silence his supporters. There is no doubt that Gandhi orchestrated the spectacle.

The very first speech that Gandhi made in India in 1915 after he had had returned from South Africa shows Gandhi in his true light and the remarks he made on that occasion do not reflect well on him.

The Gujarat Society (Gurjar Sabha) organised a garden party to welcome Gandhi on his return. As a leading light of the Indian Congress and of the Indian independence movement, Mohamed Ali Jinnah presided at the event and made a warm speech welcoming Gandhi. Jinnah was an all India leader at the time and was committed to the goal of Hindu-Muslim unity. Gokhale had called Jinnah the ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity. Sarojini Naidu went further and hailed him as the finest ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity. Jinnah firmly believed that if the two communities worked together, the British could be pressurised to leave India.

Jinnah said that Gandhi deserved the welcome not only of the Gurjar Sabha and of Gujarat but of the whole of India and that Gandhi would become a worthy ornament of India. Jinnah spoke of his belief that with co-operation between the two communities the demands of India may be made unanimously.

Stanley Wolpert, in his ‘Jinnah of Pakistan’, has commented on Gandhi’s response to Jinnah’s speech, so let Wolpert continue: “Gandhi’s response to Jinnah’s urbane welcome was that he was ‘glad to find a Mahomedan not only belonging to his own region’s Sabha, but chairing it.’ Had he meant to be malicious rather than his usual ingenuous self, Gandhi could not have contrived a more cleverly patronizing barb, for he was not actually insulting Jinnah, after all, just informing every one of his minority religious identity. What an odd fact to single out for comment about this multifaceted man, whose dress, behavior, speech and manner totally belied any resemblance to his religious affiliation! Jinnah, in fact, hoped by his Anglophile appearance and secular wit and wisdom to convince the Hindu majority of his colleagues and countrymen that he was, indeed, as qualified to lead any of their public organizations as Gokhale, or Wedderburn, or Dadabhai. Yet here, in the first public words Gandhi uttered about him, every one had to note that Jinnah was a Mahommedan”.

One time Foreign Minister of India Jaswant Singh, in his study of ‘Jinnah: India, Partition and Independence’, has described as ungracious Gandhi’s reply to Jinnah’s warm welcome. Gandhi could not get over his narrow-mindedness and saw Jinnah purely in terms of a Muslim. Jaswant Singh says further that Gandhi’s leadership ‘had almost an entirely religious provincial flavour’ while Jinnah’s was ‘imbued by a non-sectarian nationalistic zeal’.

A sadhu, but no saint

Gandhi said of himself that whereas most religious men he had met were in fact politicians in disguise, he himself wore the garb of a politician but was at heart a religious man. Gandhi’s moral teaching was grounded in Hindu dogma and it became inseparable from his political philosophy. The goal of Indian nationalism as envisioned by Gandhi was Ram Rajya.

Nirad Chaudhury corroborates that Gandhi’s ideas were rooted in Hindu mythology. According to Chaudhury, Gandhi ‘took politics into religion in order to become a new kind of religious prophet’. His political ideas belonged to the myths of Hindu political life grounded on the ideal of a Ram-rajya. Gandhi could only be a man of religion even when playing politics. “Americans should know that my politics are derived from my religion”, he wrote to journalist William Shirer.

He was a sadhu – a guru covered in a political cloak. As sadhus do, he established an ashram, attracted acolytes, and imposed his way of life upon his disciples. In the manner of many holy men, he stubbornly insisted on the payment of a standard fee of five rupees for the privilege of getting his autograph. Sarojini Naidu said it cost the nation a fortune to keep the man who gave up the business suit for the loin cloth to live in poverty. He was always financially dependent on the support of billionaire industrialist Birla, among others.

He had retainers to cater to his every need and they were of such countenance that they ‘did not speak spontaneously to anyone who did not belong to the order of worldly power and position’. Gandhi’s son Devdas made a proposal to prominent journalist Chalapathi Rau for the latter to join Gandhi’s secretariat. Chalapathi Rau asked that he be allowed to spend two days in the Sevagram to study life there and to reflect on the proposal. The two days he spent with Gandhi and his entourage convinced him that he would not fit in because he ‘saw too much pettiness there, too many faddists, too many fanatics; there was discrimination even in serving food.’

It irritated Nirad Chaudhury to have witnessed a feeble Tagore, panting his way up the stairs to pay obeisance to Gandhi, even if the sage had disapproved of the sadhu’s political ideas. He saw it as a demonstration of the superiority of the holy man over the poet, the aging sage succumbing to sycophancy to the sadhu.

Jinnah

Jinnah by contrast did not assume the posture of a religious leader. He once told a crowd: “I’m not your religious leader. I’m your political leader.” Jinnah’s Urdu was broken and he spoke mainly in English but it did not deter large crowds gathering to listen to him.

Jinnah believed that Gandhi’s civil disobedience campaign would result in increased violence and that the constitutional way was the right way. Jinnah did not believe that the Indian masses had the necessary education and sophistication to ensure that their protests were non-violent. Indeed, in South Africa, Gandhi’s movement of passive resistance had led to riots. In South Africa, Gandhi did neither pit himself against white rule nor advance the cause of the native people’s right to self-determination. His efforts were limited to protesting against the treatment of well to do Indians in South Africa.

Subash Chandra Bose

Bose was a fascist and had a running feud with Gandhi. As Nirad Chadhury says, Bose imbibed conservative Hinduism as part of his political outlook.

He became president of Congress in 1938, a position that had eluded him until then, and in 1939 he contested and won again despite Gandhi’s disapproval, defeating Gandhi’s preferred candidate Pattabhi Sitaramayya. Until then, the candidate was usually chosen by consensus with Gandhi’s approval, and he then ran unopposed and was elected unanimously, but Bose had dared to defy Gandhi the kingmaker.

Prior to the election, Bose had issued a press statement in which he had accused that the Gandhians within the Congress were less anti-British than he was and that they had a secret understanding with the British to work with the provisions of the Government of India Act 1935, which Congress had rejected. Bose argued that by willing to work with the provisions of the Government of India Act 1935 Gandhi and his allies would hinder the progress towards full Indian independence.

Congress Party leaders decided not to boycott the elections for provincial legislatures which were held in early 1937. The party won a substantial number of seats in the provincial legislatures, and the prospect of exercising power was something that the leadership was disinclined to give up.

Gandhi was unforgiving of Bose and neither he nor his supporters took things lying down. The old guard within the Congress, orchestrated by Gandhi, demanded that Bose retract from his statement. Eventually matters came to a head and Bose was forced to resign.

Ambedkar and Gandhi

Writer Arundhati Roy has given a damning verdict on Gandhi, stating that Gandhi does not deserve the reputation that he has. Ambedkar challenged the caste system that oppressed the untouchables. Ambedkar believed that it was not enough to remove the stigma attaching to caste and wanted it dismantled altogether. Gandhi made a show of fighting against the practice of untouchability but never denounced the caste system. To Roy, the ‘real violence of caste was the denial of entitlement: to land, to wealth, to knowledge, to equal entitlement’. In Roy’s view, Ambedkar challenged Gandhi not only politically and intellectually but also morally and he was Gandhi’s most formidable adversary. Yet, history has been kind to Gandhi but not to Ambedkar.

Gandhi in South Africa

Conventional narratives about Gandhi portray him as a crusading lawyer whose experience in South Africa shaped his ideas and beliefs. Roy has explodes this myth and depicts a different picture of the man who in actual fact fought for the rights and privileges of the Indian trading community in South Africa and distanced himself from the indentured Indian labour and the native blacks. He was offended that the Indian merchants were treated on a par with the native black Africans. Gandhi referred to the latter as ‘kaffirs’.

Gandhi has been described by one of his biographers as a racial purist and that he was proud of it. In 1903, Gandhi wrote that the British Indians ‘admit the British race should be the dominant race in South Africa.’

He sided with the British in the Boer war and enlisted in their Ambulance Corps. Years later, fighting broke out between the well-armed British and the spear wielding Zulus, who rose against the British over the imposition of a poll tax. It did not deter Gandhi from volunteering once again to serve on the side of the British. Gandhi wrote at the time: ‘It is not for us to say whether the revolt of the kaffirs (Zulus) is justified or not. We are in Natal by virtue of British power. Our very existence depends on it. It is therefore our duty to render whatever help we can.’ Gandhi even tried unsuccessfully to have his Indian volunteers armed against the Zulus.

The popular version of Gandhi is very far from the truth. Historian Patrick French’s verdict on Gandhi is that he ‘was an extremely wily politician, who failed to listen to the opinions of his opponents’ and Gandhi’s actions at the Second Round Table Conference of 1931 corroborate the assessment made by French.

Gandhi was strongly opposed to the demands by the untouchables for separate electorates. In London, Gandhi offered to concede to the demands of the Muslim delegation on the condition that they should not support the special claims of untouchables, particularly their claim to special representation. The Muslim delegation, led by Aga Khan, refused.

The sin of partition

Prime Minister Modi, in a speech he made in 2013, accused Congress of having committed the cardinal sin of dividing India. Maulana Azad, a prominent figure in the Congress, and author of ‘India Wins Freedom’ says how Mountbatten, when he found Sardar Patel receptive to his idea of partition, ‘put out all the charm and power of his personality to win over the Sardar.’ After he had convinced Sardar Patel, Mountbatten turned his attention to Jawaharlal. Azad says: ‘Jawaharlal was not at first at all willing and reacted violently against the very idea of partition, but Lord Mountbatten persisted till step by step Jawaharlal’s opposition was worn down’.

Azad had pinned his hopes on Gandhi to scupper the idea but when he met Gandhi he was shocked to find that Gandhi, too, had changed. ‘He (Gandhi) was still not openly in favour of partition but he no longer spoke so vehemently against it. What surprised and shocked me even more was that he began to repeat the arguments which Sardar Patel had already used. For over two hours I pleaded with him but could make no impression on him.’

Katju may have a point after all.