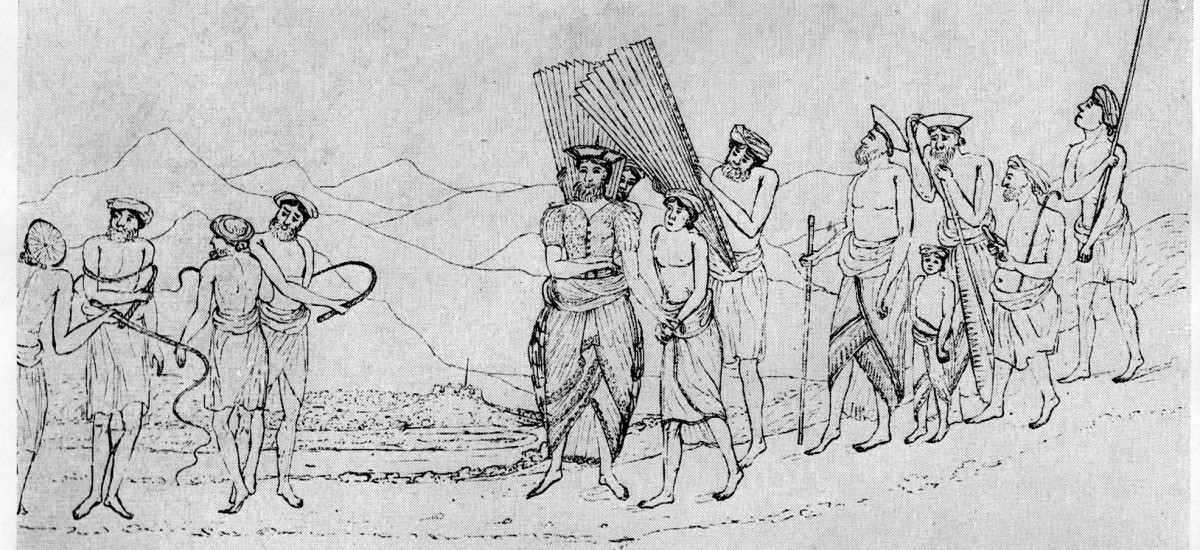

Picture courtesy Thuppahi

Work on the third edition of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) has been underway since the turn of the century, but will not be finished for another decade or two. It is likely to have a staggering 600,000 main entries, double the number of the second edition which included over 200 words of Sri Lankan origin or association.

A few years ago, malkoha, “flower cuckoo” in Sinhala, was added, a “glittering enigmatic jewel in the canopy” as this bird has been described.

Now three other words have been incorporated, adigar, aiya and aiya.

As the Sri Lankan English consultant to the OED I have lobbied for the inclusion of adigar as there are entries for both dissava and ratemahatmaya. Regarding the etymology of adigar the OED states: “Originally Portuguese adigar person in authority, governor, one of the chief ministers of the Kingdom of Kandy. Tamil atikari < Sanskrit adhikarin person possessing authority, governor (to be placed at the head, to be at the head, to superintend and partly (with special reference to Kandy) Tamil atikaram chief minister of the Kingdom of Kandy. Compare Sinhala adhikara.”

The first sense of the word, now deemed historical, is defined thus: “In the (former) Kingdom of Kandy in Sri Lanka: (a title of) a chief minister and royal adviser. Subsequently (during British colonial rule): an honorary title. The honorary office of First Adigar fell into abeyance upon the death of the most recent incumbent in 1963.”

The illustrative quotations included in the entry reveal that this word, like many others, was first used in the English language by Robert Knox in An Historical Relation of Ceylon (1681): “There are two, who are the greatest and highest Officers in the Land. They are called Adigars, I may term them Chief Judges; under whom is the Government of the Cities, and the Countries also in the Vacancy of other Governors.”

This is of special concern to me as my glossary Knox’s Words (2004) is now incomplete. Another word attributed to Knox, ambalama, is also likely to make its way into the third edition.

A further illustrative quotation from literature regarding the island is by James Cordiner from A Description of Ceylon (1807): “The second Adigar, a man of integrity rare in the court of Candy, was beheaded on account of his attachment to the family of his late sovereign.”

Other quotations include: “Next in rank to the Kandian Sovereign were the first, second and third Adigars, conjoint Prime Ministers, Commanders in Chief, and Judges of the Appellate Court,” by A. M. Ferguson from Souvenirs in Ceylon (1869).

Ponnambalam Ramanathan is quoted from Riots and Martial Law in Ceylon in 1915 (1916): “In 1903 the rank of Dissawe was conferred on him, and the still higher rank of Adigar in 1906, while holding the office of Ratemahatmaya.”

The most recent quotation is by Nira Wickremasinghe from Sri Lanka and the Modern Age (2006). “Until 1818, when a British proclamation extended the privilege of having a tiled house to a larger group than the adigars.”

Sense 2 is defined: “Elsewhere in Sri Lanka and in southern India: any of various ministers or officials; a headman or chief.”

There are illustrative quotations from international sources but just one from the island’s literature, by H. W. Codrington from A Short History of Ceylon (1926): “Each Korale or division of a disavany was under an Adigar.”

The entry for aiya provides the etymology: “Sinhala ayiya older brother, also used as form of address for an older male relative more generally < Tamil aiyan, ayya father, also used to modify the word for ‘brother’ to convey the sense ‘elder’, and as a respectful form of address to male superiors more generally.”

The definition: “In Sri Lanka: an older brother. Hence more generally: any older male relative or acquaintance. Frequently as a form of address. Also as a postmodifier with a proper noun.”

It is satisfying that all four illustrative quotations are from Sri Lankan literature. The first to use the word was Leonard Woolf in The Village in the Jungle (1913): “‘Will you sit down, aiya?’ said Babun.”

Colvin de Silva writes in The Winds of Sinhala (1982): “‘Because it concerns aiya.’ Some of the smirk left the Queen’s face. ‘What has our firstborn been up to?’”

In Romesh Gunasekera’s Monkfish Moon (1992) can be found: “Call him, I said. Tell him Victor aiya has come.”

The most recent quotation is by Swarna Wickremeratne from Buddha in Sri Lanka: Remembered Yesterdays (2006): “In every household he was a bit of a heartthrob to the female servants, who gathered round to exchange small talk with ‘Martin aiya’ (brother Martin)”.

The final word of the trio of OED newcomers, aiyo, has the simple etymology, “Sinhala ayiyo and its probable etymon (ii) Tamil aiyo, of imitative origin.” The definition: “In southern India and Sri Lanka, expressing distress, regret, or grief; ‘Oh no!’, ‘Oh dear!’”

The first writer to use in the word in English was Leonard Woolf in The Village in the Jungle (1913): “Aiyo! aiyo! My little Podi Sinho!”

The next illustrative quotation is from then Ceylon’s Fashion Panorama (1971): “‘Aiyo! it is our Kalu’ they all cried.”

And the most modern is by S. Manickavasagam in Power of Passion (2009):

“Vijaya touched Rajam’s forehead and exclaimed, ‘Aiyo. She is running very high temperature.’”

I should add that the third edition is evolving online, and is unlikely to be published in a series of volumes, as was the second edition. The work, however, is unable to be viewed without a subscription.