“Hope to achieve political settlement through adoption of a new constitution. Don’t judge us by broken promises of past” says Foreign Minister Mangala Samaraweera at UNHRC in Geneva, on 14th September 2015.

The statement in September by Sri Lanka’s Foreign Minister provided a timely frame of reference to appreciate the ‘Corridors of Power’ exhibition. From the security guards at the venue of the exhibition to international constitution building process experts who gathered in Sri Lanka at the time around a workshop on constitutional reform, from students to academics and activists, ‘Corridors of Power’ even before officially opening to the public generated more interest than any project curated by Groundviews and the Centre for Policy Alternatives previously.

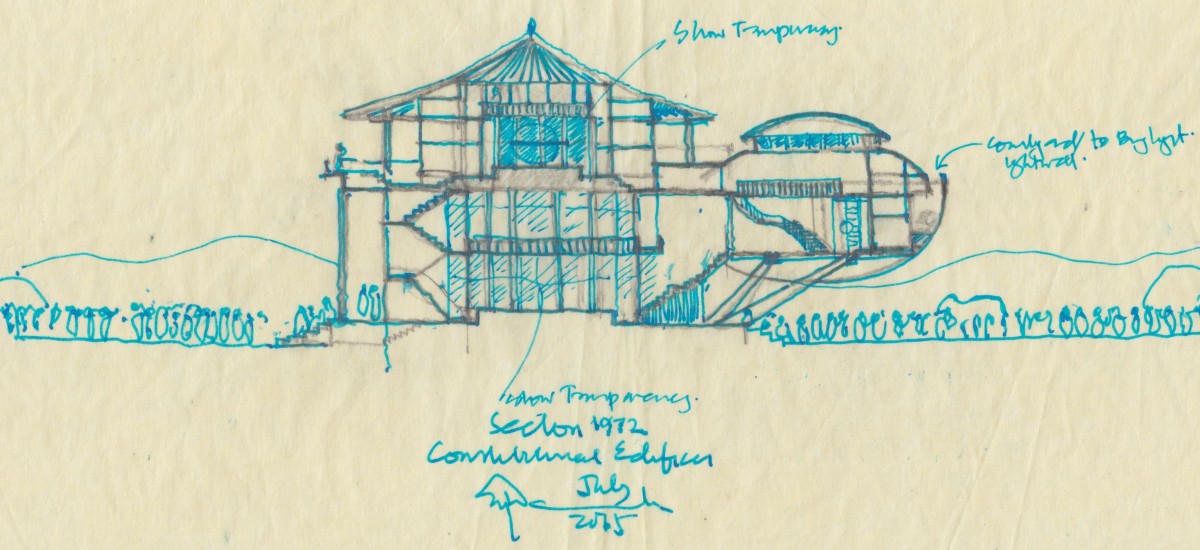

Led by the input of Asanga Welikala, in collaboration with Channa Daswatta, ‘Corridors of Power’ through architectural drawings and models, interrogated Sri Lanka’s constitutional evolution since 1972.

The exhibition depicted Sri Lanka’s tryst with constitutional reform and essentially the tension between centre and periphery. The output on display included large format drawings, 3D flyovers, sketches, and models reflecting the power dynamics enshrined in the the 1972 and 1978 constitutions, as well as the 13th, 18th and 19th Amendments.

To our knowledge, nothing along these lines was ever attempted or created before. In addition to the exhibits on display, each day featured a keynote presentation or panel discussion by eminent individuals, around the topic of constitutional reform in general. All the submissions, including the Q&A session, were recorded and are now available online.

Access them as a playlist here, or download each podcast / recording from here.

- Facebook event page

- Lineup of keynote speakers, including those from Government, respondents and panellists

- Note by Curator (Sanjana Hattotuwa)

~

16th September, The constitutional vision of the new government (Keynote)

As reported in the media in May this year, Jayampathy Wickramaratne, the leader of a three-member team that prepared the 19th Amendment, called for a new Constitution which will include a fresh Bill of Rights and address the issues of devolution of powers to provincial councils and power sharing at the Centre. After the General Election on 17th August, Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe was reported in the media expressing hope that a political consensus could be reached within months on a new Constitution for Sri Lanka, because in his opinion the issues that needed to be resolved were fairly narrow. This triumph of hope and optimism over bitter experience may not last long, and the window for substantive changes in Sri Lanka’s constitutional fabric is small. If our present constitution is fundamentally unsound, what can be done in imagining a new one to ensure the flaws are addressed? And if in addressing these flaws, hard choices have to be made, how can a constitutional reform process secure the requisite political will, above purely parochial and expedient considerations, to stay the course? How will citizens be a part of this process – as mere onlookers, or as active participants? What are the core values the government will anchor the new constitution to and seek through its passage, the entrenchment of in the popular imagination? Ultimately, independent of the success or failure of the project around a new constitution, what does the new government aim to achieve around constitutional reform in a manner qualitatively different to attempts in the past?

- Jayampathy Wickramaratne MP

- Respondent: Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu