“Hope to achieve political settlement through adoption of a new constitution. Don’t judge us by broken promises of past” says Foreign Minister Mangala Samaraweera at UNHRC in Geneva, on 14th September 2015.

The statement in September by Sri Lanka’s Foreign Minister provided a timely frame of reference to appreciate the ‘Corridors of Power’ exhibition. From the security guards at the venue of the exhibition to international constitution building process experts who gathered in Sri Lanka at the time around a workshop on constitutional reform, from students to academics and activists, ‘Corridors of Power’ even before officially opening to the public generated more interest than any project curated by Groundviews and the Centre for Policy Alternatives previously.

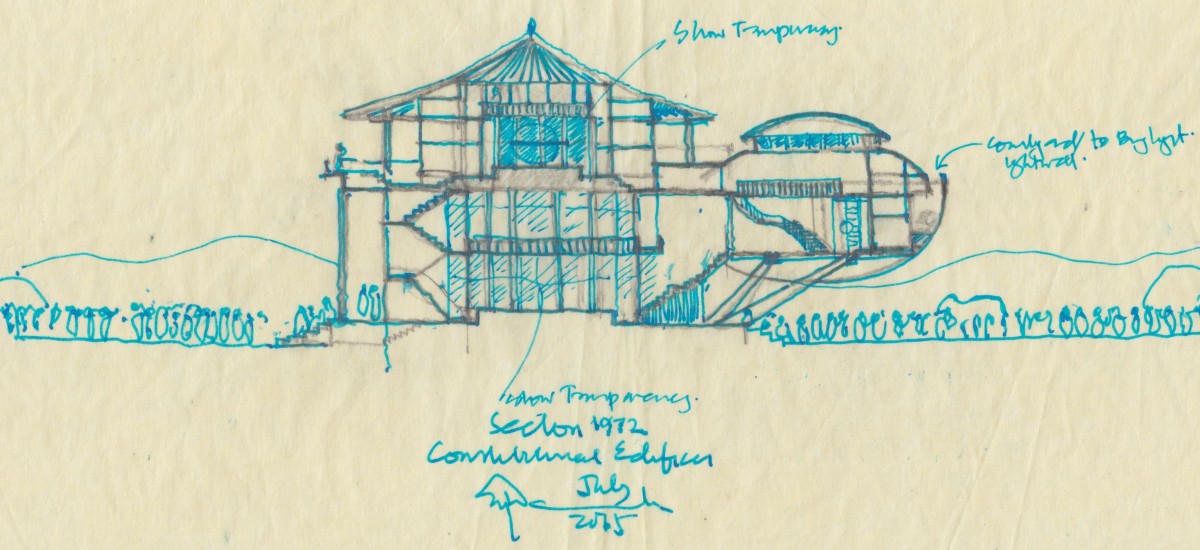

Led by the input of Asanga Welikala, in collaboration with Channa Daswatta, ‘Corridors of Power’ through architectural drawings and models, interrogated Sri Lanka’s constitutional evolution since 1972.

The exhibition depicted Sri Lanka’s tryst with constitutional reform and essentially the tension between centre and periphery. The output on display included large format drawings, 3D flyovers, sketches, and models reflecting the power dynamics enshrined in the the 1972 and 1978 constitutions, as well as the 13th, 18th and 19th Amendments.

To our knowledge, nothing along these lines was ever attempted or created before. In addition to the exhibits on display, each day featured a keynote presentation or panel discussion by eminent individuals, around the topic of constitutional reform in general. All the submissions, including the Q&A session, were recorded and are now available online.

Access them as a playlist here, or download each podcast / recording from here.

- Facebook event page

- Lineup of keynote speakers, including those from Government, respondents and panellists

- Note by Curator (Sanjana Hattotuwa)

~

18th September, The chiaroscuro of power: Architecture’s role in hegemony and change (Keynote)

Channa’s note on this exhibition avers thst “the premise has been that architecture is essentially about creating relationships between various spaces occupied by people and thus making the potential for interaction between them.” When the Design Museum in London named world renowned Hahid’s Heydar Aliyev Centre in Baku, Azerbaijan, the winner of the Design of the Year award in 2014, critics noted that Hahid’s lack of concern over who commissioned the edifice, and who it commemorates, was deplorable. As Russell Curtis, a founding director of London-based architects RCKa, an award-winning design practice noted at the time and in response to the award, “It’s naive to believe that architecture and politics are mutually exclusive: the two are inextricably linked.” What is an architect’s role, if any, in critiquing the status quo? Is there a greater social or civic responsibility around public projects, for example those commissioned by the State, or does the client, which could be an authoritarian government, to the exclusion of all other voices, determine the final structure and order of things? What are instances where architecture, through design or appropriation and in terms of the geo-spatial organisation of space, has fuelled reform and even revolt? And if that is possible, is the converse also true – can architecture create more harmonious social relations through spatial relationships?

- Channa Daswatta

- Respondent: Sunela Jayawardene