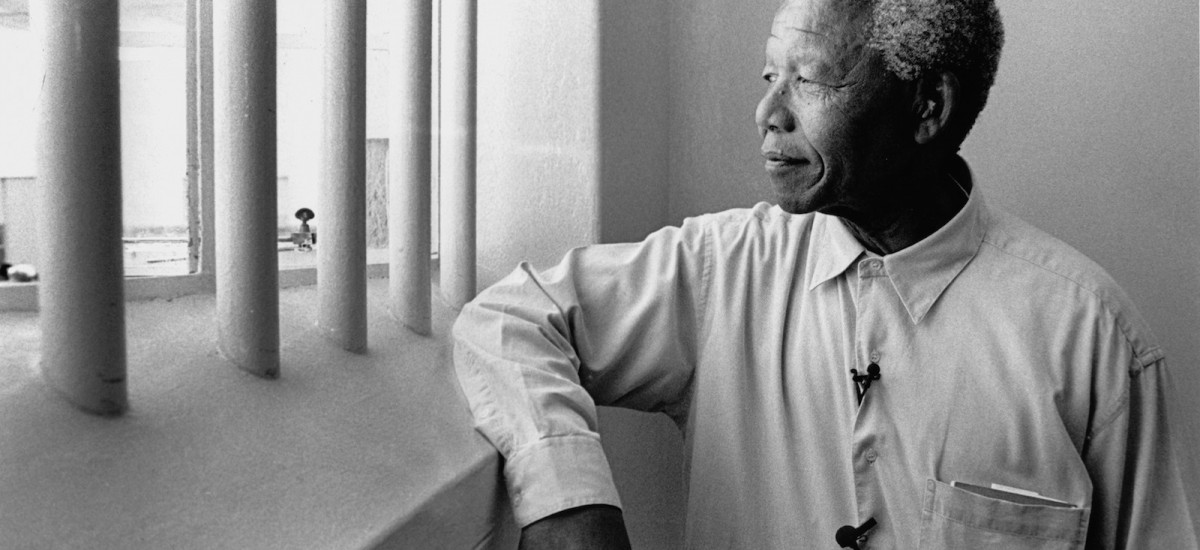

Photograph courtesy National Geographic

Give me that man

That is not passion’s slave, and I will wear him

In my heart’s core

Hamlet, Act 3, Scene 2

The death of the moral colossus in the politics of our time has occasioned a worldwide celebration of all things bright and beautiful that he represented in such abundant measure and to such inspirational effect. Not only for his fellow South Africans, but also for the rest of the world, Nelson Mandela personified a superhuman standard of humility, dignity, courage, resilience and forgiveness. As a model of political leadership, his example of bringing the metaphysical ideals of democracy as close as might be possible to the ugly realities of everyday politics will be difficult if not impossible to emulate. His political life and conduct demonstrates the unique combination of Passion and Reason, intellectual depth and moral decency that separates populists from democrats, politicians from statesmen, demagogues from nation-builders. To quote one of his predecessors in the pantheon of greats, “A moment comes, which comes but rarely in history, when we step out from the old to the new, when an age ends, and when the soul of a nation, long suppressed finds utterance.” Like with Nehru in India, it was South Africa’s good fortune that when the moment came, Mandela was there to lead it to “life and freedom.” If that nation-building moment brought out the best in these men, they also used their brilliance and integrity to shape the moment. They imprinted upon their national histories the memory of the higher order values of consent, tolerance, and pluralism, which forged the unity of their nations at their birth. Their concrete legacies are enshrined in the modern constitutions they helped mould.

In South Africa, it would have been the politically easy – and morally unobjectionable – course for Mandela to have led the establishment of a revolutionary new republic, breaking all constitutional ties with the apartheid legal order and instantiating untrammelled majority-rule. In line with the long-held position of the ANC, this would have taken the constitutional form of a unitary state. Such a state would have centralised power horizontally in favour of the executive, because a strong executive unhindered by parliamentary and judicial checks was needed for the accelerated development so badly needed by the black majority. It would have centralised power vertically, sweeping away the corrupt, inefficient and illegitimate anomaly of federalism that had found articulation in the old Bantustans. No one would have been able to criticise such a choice of constitutional model after the abomination of apartheid.

Instead, Nelson Mandela presided over the making of a constitution that eschewed revolution, centralisation and ideological dogmatism. When the case for a complete break with the past could not have been more morally clear, South Africans decided to carefully preserve formal constitutional continuity. From bitter experience elsewhere in Africa, they knew that constitutional revolutions, however justifiable in quotidian circumstances, were in the longer term a destructive precedent for constitutional democracy. The Presidency and the National Assembly, the institutions of majoritarian power, were firmly subjected to the separation of powers and the constitutional control of each other and a powerful Constitutional Court. They introduced a Bill of Rights enforced by an independent judiciary that not only circumscribed political power, but also set out a positive basis for citizenship. In the preservation of cultural and regional diversity, the South African constitution is federal in all but name. In rejecting the outmoded centralising shibboleths of Cold War-era socialism that many still expected of the ANC, they realised the strong democratising dynamism of a federal system of government that could deliver not only better government, but also stronger and more balanced economic growth and development.

To be sure, not all of this was Mandela’s sole achievement. Like in India four decades before, South Africa in the 1990s also had a broad and deep class of political leaders and a vibrant intelligentsia and civil society that came into their own in the making of the constitution. But Nelson Mandela provided the core moral perspectives, a pervading sense of decency and fairness, the inspirational oratory, and the reconciliatory ethos for the new order of political justice that the South African constitution would establish. His own ideals ultimately informed not only the substance but also the interpretive spirit of the constitution, the fundamental legal foundation of the new ‘Rainbow Nation.’ In all these respects, therefore, his modernist leadership was central to the establishment, not of a backward-looking nation limited by the hatreds of the past, or a majoritarian unitary state that would traduce pluralism and inclusivity, or a debilitating African presidential monarchy, but a forward-looking constitutional democracy that inspired, rather than imposed, unity in an otherwise divided plural society, by embracing the universal ideals of the democratic way of life. None of this was preordained. If Mandela was more of an ANC ideological dogmatist and less of a liberal democratic pragmatist, each of these constitutional choices could have been decided differently and for the worse.

Like with Nehru, Mandela’s puissant leadership was founded on the strength of his character and his unerring moral compass, his intelligence, education and cultured urbanity. This is what enabled the rejection of the nativism and the rancour that has characterised the unprincipled use of nationalism all over the post-colonial world, and which has marred and continues to derail democratic nation-building. Jawaharlal Nehru once told John Kenneth Galbraith that he was the last Englishman to rule India. President Mandela’s legal advisor once told me that the striking impression of his personality was that of a public school-educated Edwardian gentleman: a devout votary of the British parliamentary tradition, he had a lawyer’s highly developed sense of constitutional propriety in his approach to politics, and was possessed of courtly manners and a thoroughly Anglophile sense of humour. There is a broader and much more important lesson than cultural sycophancy in these anecdotes. It is that nation-builders of this rare quality are able to take constitutional lessons and learn the best practices of democratic statecraft from elsewhere, without fearing for their own identities or endangering their sense of patriotism. By imparting these traits to the nations they help found, such statesmen create not only free and open societies but also peaceful and stable states, unlike paranoid populists whose only method of political mobilisation is the versatile use of fear. The freedom from fear imbued Nelson Mandela’s personal conduct and political creed throughout his life, and it is the leadership attribute that ensured a plural and inclusive constitutional democracy in his motherland. It is unfortunately not an example that many Asian and African leaders have had the will, the capacity or the character to follow.