Robert S McNamara, who was US Secretary of Defence under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, then served as President of the World Bank from 1968 to 1981. Despite his contentious legacy in the US government, he is credited to have shifted the Bank’s focus to population and poverty issues.

McNamara, whom I once interviewed when in retirement, had a razor sharp mind and a wit to match. The story goes how, in the early days of his Bank appointment, he was visited by three highly accomplished Ceylonese officials — all of who happened to be well built men.

“Do you gentlemen represent the starving millions of Ceylon?” McNamara reportedly asked them with a sarcastic smile.

“No Sir,” one of them replied. “We represent their aspirations!”

The Ceylonese trio – who epitomized the Golden Era of Lankan diplomacy – were Sir Senerat Gunewardene, Shirley Amerasinghe and Gamani Corea. Thus have I heard.

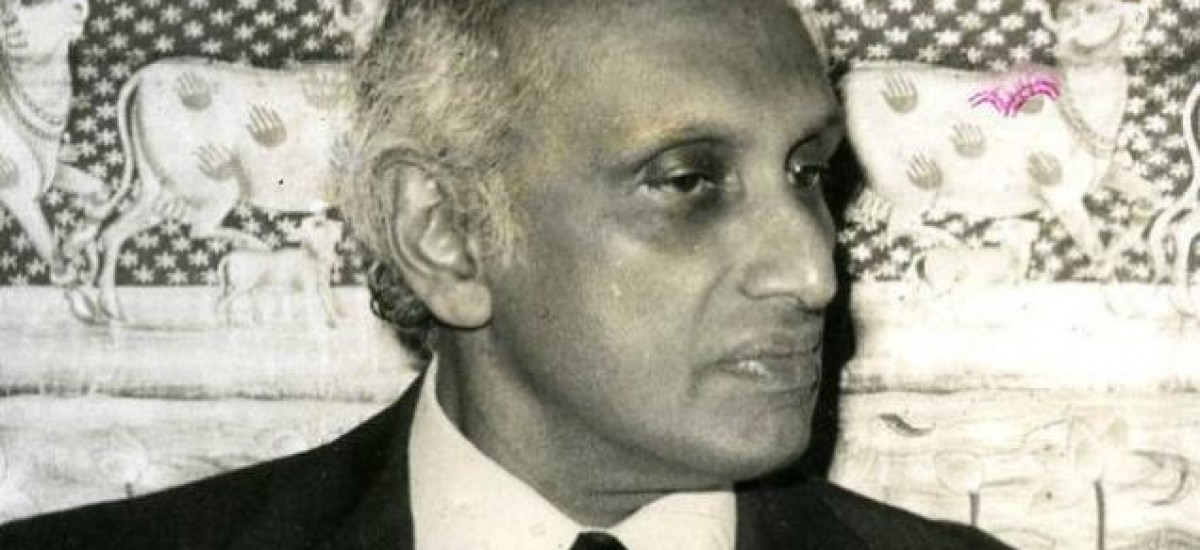

The last of these giants, Dr Gamani Corea (1925-2013), died last week after an illustrious career in economics, planning, international development and scholarship that spanned over half a century.

Corea was an Oxbridge qualified technocrat who steered newly independent Ceylon’s economic planning and fiscal management. Successive governments engaged his services: in his memoirs, released a few years ago, he revealed how he had twice declined offers by heads of government to be made the finance minister (in 1965 by Dudley Senanayake, and in 1988 by J R Jayewardene when Ronnie de Mel stepped down).

A Just World

If those are footnotes of history, Corea is best remembered – and celebrated — internationally for his role as Secretary General of UNCTAD (UN Conference on Trade and Development). He held the post for four consecutive terms from 1974 to 1984, and was noted for his vision of a rebalanced international economic order that would provide fairer treatment to developing countries.

In fact, his engagement with UNCTAD dated back to the organization’s founding, when he helped to create the Group of 77 alliance of developing countries at the first session of UNCTAD in 1964.

As the UNCTAD website noted: “As Secretary General, he had a reputation as an intellectual who pursued the idea of international economic reforms that could give the world’s poorer nations a better chance of long-term development and more effective results from trade.”

Among the many tributes that have appeared, one of the most perceptive came from the senior Indian journalist Chakravarthi Raghavan, a noted commentator on global North-South relations.

Raghavan wrote in the Inter Press Service (IPS): “He [Corea] had an inner conviction and strength, a visionary and developmentalist, despite his affluent personal background, and within UNCTAD developed several programmes to help development, and remained firm in his view that UNCTAD should remain a part of the UN, an organ of the UN General Assembly devoted to Trade and Development.”

Some UNCTAD initiatives supported during Corea’s time had far reaching implications. Notable among them: policies based on rational pharmaceutical drugs use in developing countries, which was a joint advocacy with WHO.

Two Lankan experts, Dr Senake Bibile and later Dr Kumariah Balasubramaniam, led this effort that benefited tens of millions.

Raghavan also commented on Corea’s style of diplomacy, which was charming and lacked intellectual arrogance. Yet, “while not confrontational or using harsh language, he stood up throughout his tenure to pressures and bullying tactics of the United States or European Communities and their attempts to influence senior staff appointments by planting their own men.” (Full text: http://tiny.cc/CRGC)

Gamani Corea (on right) greets his predecessor at UNCTAD Manual Perez Guerrero on 1 February 1974

Sharp Wit

Corea’s wit has endured long after he left the UN system and international development circles. One memorable quote attributed to him from the 1970s: “Many developing countries of Asia and Africa share one common minister of Finance: the World Bank and IMF!”

Raghavan notes how Corea withstood pressure from the IMF and World Bank, “whose leadership attempted sometimes, as an observer at UNCTAD Board meetings, to scoff at UNCTAD views, and any alternative thinking differing from IMF/World Bank ideology and rulebook”.

Corea remained an elder statesman of international development for many years after leaving UNCTAD. Among many appointments, he was a member of the South Commission and later chaired the Board of the South Centre in Geneva.

An early supporter of sustainable development, Corea deftly avoided activist rhetoric and academic fluff that dominates international debates on the subject. Working with credible groups like the Third World Network, he guided civil society preparations for the UN Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992.

At the summit itself, he was on the official Lankan delegation which was led by Prime Minister D B Wijetunge. There, in an interview with the Lankan-born journalist Thalif Deen of IPS, Corea famously summed up the event’s disappointing outcome: “We negotiated the size of the zero!”

Early on in the Asian economic boom, Corea saw science and technology (S&T) accelerating growth and raising quality of life in the developing countries. In an interview given to me in 1990, he called S&T “the determinant of economic, social and even political success of developing countries in the future”.

He added: “The world in which we live is one where knowledge assumes major importance. Already, people are saying that the gap of the future will not be between industrialised and non-industrialised countries, or between rich and poor nations, but between those who have knowledge and those who do not.”

At that time, the Cold War had only just ended. Personal computers were clunky, slow and costly. And the Internet was a privilege available only to a few thousand academics and military personnel.

Close Encounters

I first met Corea when I was a young science reporter working for Asia Technology magazine published from Hong Kong. Corea was dividing his time between Colombo and Geneva.

My editors wanted me to get his insights on a proposal he had made that year: to revamp the Colombo Plan — an inter-governmental organisation to strengthen economic and social development of countries in the Asia Pacific region — with a new focus on S&T.

Corea didn’t know me before, but was highly approachable and amiable. He matched my eagerness with crisp, optimistic answers. We chatted for almost an hour.

When it came to taking a photo, he was shy and hesitant. “I have a rather large nose that dominates all my photos,” he said as I asked him to pose in his spacious garden at Horton Place.

“Then how come your nose isn’t as famous as JR’s?” I asked. Our first Executive President’s prominent nose had been the delight of cartoonists for decades.

What struck me was Corea’s complete lack of pomposity, and his child-like enthusiasm.

Our paths crossed again a couple of times. A few months after our interview, Corea chaired a meeting on holistic development at the Subodhi Institute in Piliyandala where I was a panelist.

The last time we met was in Geneva, and I remember the exact date: 23 April 1993, when Lalith Athulathmudali was assassinated at a public rally in Colombo. My then boss Vitus Fernando took me along for a belated New Year celebration of Lankans living in Switzerland.

Corea came in for a brief while and talked to the young and old, but he wasn’t his usual self. He just sat there looking distraught and perplexed. The destiny of the young nation that his generation had shaped was suddenly very uncertain.

As the band played on and some danced into the tranquil Geneva night, my generation’s future was falling apart in far away Colombo…

Science writer Nalaka Gunawardene blogs at http://nalakagunawardene.com, and is on Twitter at: @NalakaG