Image courtesy National Youth Front

A Genre Defying Future Classic on the Psyche of a Republic

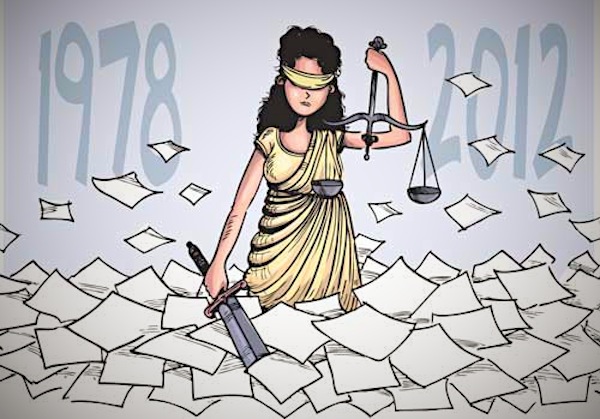

A contemporary masterpiece that interweaves fact, fiction and fantasy with seamless and vibrant prose, the Constitution is a must read for all literature lovers. The Constitution was first published in 1978 in not one, but three languages – the only piece of literature in the reviewers understanding to be thus translated at its very outset – an indication of the confidence that the authors had in its literary value and broad appeal. Due to popular demand, eighteen new editions have been published since, each with minor (and sometimes major) improvements. The book is so popular that moves in 2000 to cease publication and replace with another text were met with vehement protests and organised book burning ceremonies. In its 34-plus years of existence, the Constitution has truly proved to be a ‘living text’ – an accolade usually reserved for the masterpieces that have stood the test of time – Moby Dick, War and Peace, Mrs. Dalloway – and just like those other works it is sufficiently rich and nuanced to accommodate multiple and even contradictory interpretations based on the readers aptitude, wisdom, politics and indeed mood.

For decades, the majority of Sri Lankans have mistaken the Constitution for a non-fiction work that in some intangible manner sets out the broad framework within which society operates, thinks, values, protects and punishes. Herein lies the genius of the authors, who created a whole new literary genre – that has subsequently become known in the film world as the ‘mockumentary’ (fiction presented as fact). But the Constitution is not merely a mockumentary. It transcends other literary genres – from magical realism to absurdism, to satire and at times even Gothic horror – with the simplicity and ease that is a hallmark of true genius. Think Kafka, Allende, Coelho, Stoker, Saki, Wilde and Orwell all rolled into one, and somehow working.

That it was ahead of its time is beyond doubt, that it is probably the most influential contemporary work is rarely acknowledged.

The Constitution is to the Republic of Sri Lanka, what Rushdie’s ‘Midnight’s Children’ is to post-colonial India – the story of a history of a nation. It is flawed – as this review will explore later; but even its flaws are compelling and of literary value – full of irony, metaphor and imagery – and most importantly, integral to the story it tells.

The strength of the Constitution does not lie in its ‘plot’ – which some have argued, is ‘lost’. In this sense, the book is ‘Kundera-esque’ – to be read more for the beauty of its prose, its wisdom and philosophical insight than for a good story. Ostensibly, the very thin plot is that of the life of a republic. Consequently, the protagonists, as set out in the initial pages include ‘the people’, ‘the state’, ‘the unitary state’ (are they one and the same?), ‘sovereignty’, ‘the executive’, ‘the legislature’ and ‘the judiciary’. As the story develops, we learn about the rights of the people and how these rights are the most important and inalienable thing – but not quite. How the executive, legislature and judiciary – all manifestations of the sovereignty and power of the people – pull together to ensure that every person has the best possible chance to succeed and is guaranteed protection against any and all injustice.

That may sound like a pretty dull story – and it is. But therein lies the genius of the Constitution. No good fiction is complete without elements of conflict, tension, uncertainty and suspense. The Constitution has achieved all of the above and much much more, not through its text alone, but through how this text has been perceived and interacted with by the reader. It is only now that the ‘fiction’ element of the Constitution is being recognised, as a large metaphorical neon tube light haltingly flickers on above our collective heads. For the longest time, readers mistook the Constitution for ‘fact’ and responded to it accordingly – and thus, unknowingly became integral to the story themselves. The increasingly attractive notion of ‘creative reading’ i.e. that the reader plays an important role in the literary process, was taken to the next level by the Constitution in a manner that has rarely been replicated since.

One example was the 2010 Joaquin Phoenix mockumentary ‘I’m Still Here’. Phoenix publicly announced his retirement as an actor and his ambition to build a new career as a hip hop artist. He proceeded to make really bad records, and visibly degenerate from one of the most talented actors in the world to a socially awkward, hobo looking terrible terrible singer. The reaction was pretty massive, and was recorded and subsequently incorporated into the mockumentary – thus making the viewer an active and not passive participant in the literary process.

The Constitution does the same. But does it better. And this is why its many flaws are so essential to its success. It is because it is a flawed document that well intentioned people were sucked into the story and made arguments and counter-arguments to improve it. One example would be the discourse around the manner in which the beautifully articulated rights of the people as enshrined in the Constitution are undermined by one stark sentence – “all existing written law and unwritten law shall be valid and operative notwithstanding any inconsistency with the preceding provisions of this Chapter.”

It is because it is a flawed document that the opportunistic rallied under seemingly counter-intuitive sections that when carefully studied, demonstrate that the people though declared to be ‘equal’, are actually not. And that while ‘People’ benefit from certain Constitutional provisions including a declaration that the state is unitary; ‘people’ do not.

And so through its flaws, the Constitution brings out the best and worst in human nature, and has made the reader part of the story. This is literature at its very best – a true reflective piece that casts a mirror on society and does not shield us from the resultant image.

But as with all good things, the Constitution could not deceive the astute readership forever. The recent impeachment of the Chief Justice, the rejection of the Supreme Court’s Constitutional interpretation and the reliance instead on an interpretation by the legislature, were perhaps a step too far and have finally confirmed that this text will go down in history as a great work of art and not a mediocre work of legal drafting.

Perhaps if we had been looking more closely though, the truth would have emerged earlier.

For example, the Thirteenth edition of the Constitution provided for some improvements that never transgressed into fact from fiction. Perhaps because most of these improvements would have benefited ‘people’, ‘People’ did not notice their non-implementation. The same could be said for the Seventeenth edition. Again, we hardly noticed.

Similarly it is not like the legislature and executive have not treated the Constitution for what it really is – fantasy – in the past. But then again, most often such acts resulted in ‘people’ not being treated in compliance with Constitutional text (which recognises them as the sovereign power with inalienable rights), like many youth of the South in the 80s or the Wanni population circa 2009 for example.

Most embarrassingly – and perhaps because it is popularly known in shorthand as ‘The Constitution’ – many a discerning reader failed to make an educated guess based on its full title – “The Constitution of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka”.

Finally, while the present state of affairs which brings into focus the ‘separation of powers’ and ‘rule of law’ is what has confirmed to many that the Constitution is indeed a work of fiction; there were many long-standing signs for those willing to look, that this has been the case for some time.

The Constitution provides for three arms of government (judiciary, legislature and executive) that have different and separate powers which counter-balance each other in order to ensure that the people remain sovereign and supreme.

But reality has been increasingly very different.

For example, despite the Seventeenth edition of the Constitution introducing improvements which enhanced the separation of powers, the very next edition brought in even better improvements which ridiculed the very notion. Furthermore, this Eighteenth edition was written by an executive, passed by a legislature and approved by a judiciary with seamless ease, almost as if all three organs were one and the ‘people’ (and ‘People’) did not matter. The three organs have colluded before – many a time to deny justice to the ‘people’ – but the separation of powers was never questioned. It is only now, when the lack of a separation has been highlighted due to conflict between the organs as opposed to collusion, that we finally have seen the light.

They say that fact is stranger than fiction. With the Constitution, they are one and the same.