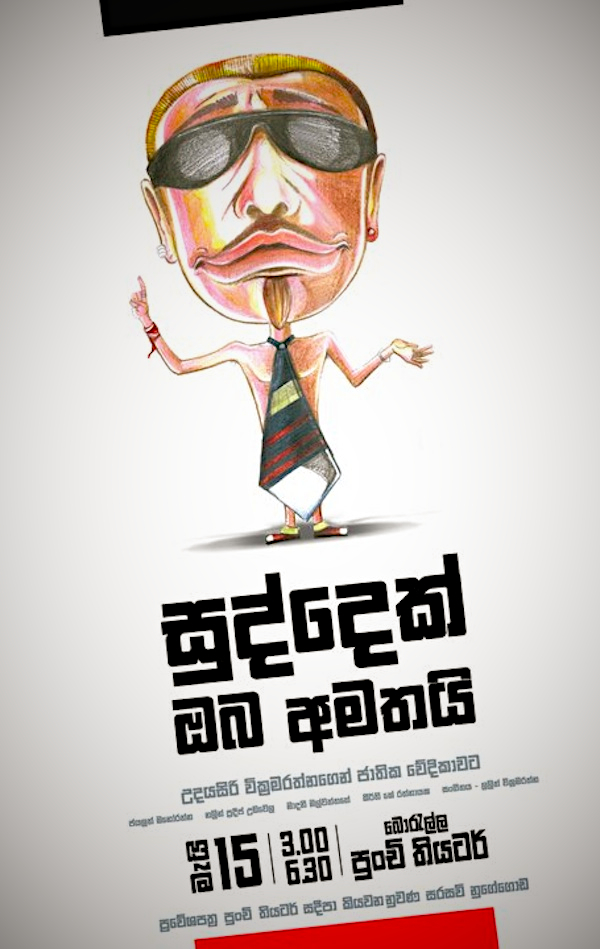

Photo courtesy Suddek Oba Amatai Facebook page

It is Lakshman Piyasena, introduced to me by my friend Jayantha Dhanapala, who first told me of Udayasiri Wickramaratne’s play. Piyasena urged Dhanapala and me to see a performance of Suddek Oba Amatai and kept us informed of dates when the play was due to go on the boards in Colombo. I am most grateful to both Messrs. Dhanapala and Piyasena for directing me to this excellent piece of theatre.

Accordingly, a few weeks ago, I was privileged to watch a production of Udayasiri Wickremaratna’s notable play Suddek Oba Amatai (A White Man Addresses You). It was a sumptuous evening at the theatre as the play stimulates the senses at the same time as it provides the audience with much food for thought. The dramatic fare on offer entertains the theatergoer as it provokes him/her to think. The acting was very good with Nalin Pradeep Udawela (who plays the role of the sudda or the white man) and Jayalath Manoratne (who plays the character that personifies history) making the first two scenes or episodes of the play go smoothly. The third scene or episode is magical with Madani Malwattage stealing the show from both Manoratne and Udawela. Hers was a wonderfully captivating, charming and brilliant performance. Her good looks, dazzling speaking and singing voice and perfectly relaxed playing had the audience spellbound. Udayasiri Wickramarane has written a marvellous play and his brother Lalith Wickramaratne, the director of the play’s music, has contributed handsomely to the overall production.

It is a pity that the Wickramaratne’s play has not received the critical attention it richly deserves in either the Sinhala or the English language press. For those amongst us who have yet not seen Suddek, I urge you to do so at the next available opportunity. You will be in for a rare treat. I certainly plan to see it more than once.

I was so taken up with the play that I sought a meeting with the playwright. He duly obliged and, over a drink, we had a near two hour conversation about Suddek and Wickramaratne’s career to-date. Thus I came to know that Wickramaratne is a graduate of the University of Colombo of the early 1990s. He was a member at that time of a Street Theatre group (Para Veedi Natya Kandayama). He began his working life as a translator at his alma mater on Thurstan Road and later on at the Ministry of Cultural Affairs. He then moved to Phoenix Advertising where he continues to be employed. His earlier ventures in the direction of drama, apart from Street Theatre, resulted in Thunweni Lokaya (The Third World) and a short play titled Eelanga Jawanikawak Nethi Natyayak (A Play With No Next Episode). Suddek first went on the boards in April 2010 and to-date has had 60 performances throughout the country, the last being at the National Drama Festival on Sunday, 22 January, 2012.

Suddek Oba Amatai is not a conventional play. In fact, its name though arresting is actually misleading. Perhaps, deliberately so? The sudda or the white man only addresses the audience in the first episode of the play. The next two episodes are titled Itihasaya Oba Amatai (History Addresses You) and Striyak Oba Amatai (A Woman Addresses You). Suddek is thus episodic and each episode, although it can stand alone, is inter-connected thematically. Suddek does not conform to Aristotelian formulae. It is an innovative and experimental piece of superb theatre. It is a fast- moving play with song and dance interspersed with spicy and entertaining dialogue that focuses sharply on some vital socio-political issues of the day. Humour and satire form an integral part of the dialogue. Suddek, therefore, may be characterized as a public conversation that Udyasiri Wickramaratne has initiated with his audiences in order to provoke thought, debate and discussion on certain vital issues of the day such as our relations (or the lack thereof?) with the west, our ignorance of our own history, our unjust and unprincipled political culture (hence the call for Sadaranatvavadaya) coupled with a discourse on our unnecessary human rivalries based on gender.

If I were to draw parallels with the English language theatre of the west, I would assert that there are elements of Shaw, Brecht and Chekov (of his shorter plays like The Bear, The Proposal or On the Harmfulness of Smoking) in Wickramaratne’s play. As with the plays of Shaw and Brecht, Suddek poses provocative questions to its audience. And as with the plays of Shaw, Brecht and Chekov, there is a great deal of entertainment in Suddek. The play is both instructive and entertaining at the same time. Thus we are reminded at significant moments of the play, especially at the moments of greatest fun and laughter, to think carefully at leisure about the vital issues that Suddek raises. In his notes to the play, Wickramaratne tells us that although he uses song and dance, Suddek is not a ‘formula’ play. Rather that it is more akin to a public lecture on some of the pressing socio-political issues of the day. If, however, it was a mere lecture minus the wit and humour in which the key arguments are presented, the response of the audience would not be as warm and appreciative as it now is. Wickramaratne has got his theatrical fundamentals right: Suddek delights as it instructs.

Although the play begins by our being asked to suspend disbelief and enter the world of make believe, there is a conscious intrusion by the playwright into real time (as opposed to theatrical time) as the play progresses. For instance, in episode one, the ‘sudda’ who addresses us is no sudda. He is a Sri Lankan playing the role of a white man. To reinforce this technique of breaking down of theatrical illusion, the playwright makes the character (played by Nalin Pradeep Udawela) at the end of episode one, to drink water from a goblet off a coconut shell (pol cutta) in the manner of a non-westernised Sri Lankan. Udawela begins the episode by taking a few sips of plastic bottled water in the manner of a tourist. Jayalath Manoratne at the end of the second episode likewise tells the audience that all he had said so far is that which Udyasriri (Wickremaratna) asked him to say! He also cautions us about the danger of history in that it is often difficult to progress if we are too wedded to history and also that, paradoxical as it may sound, if we forget history it is not possible to progress meaningfully. He admonishes us to go home and ponder over the thoughts placed before us. And Madani Malwattage who plays the role of the woman in episode three, concludes the play and her delightful role in it, by telling the audience that she has never before acted in a role such as the one she plays in Suddek, thereby bringing the audience directly into the public conversation referred to above.

The underlying theme of the play is the value of moderation in all things. The emphasis is on the avoidance of extremes as we encounter it in Greek thought (‘the golden mean’) and in Buddhist philosophy (madyama pratipadava). In the first episode the playwright suggests to us that the white man is not all evil. To think that we Sri Lankans have a monopoly on virtue and that all westerners are evil is to delude ourselves. Such thinking is both extreme and unintelligent the playwright suggests. There also seems to be a hint in the play that we may be reacting in an immature fashion to the western world, manifesting thereby an inferiority complex to it that masquerades as a superiority complex. If we are secure in our Sri Lankanness, we could be ourselves and get on with anybody else in the world regardless of which part of the universe they come from. The English language the white man speaks has enriched our lives. The achievements of the westerner in the field of science and technology, in philosophy, the arts and architecture are impressive and these are not to be scoffed at. The playwright seems to suggest that we need to discriminate between the good and the bad and absorb the good as we leave out the bad instead of blindly aping the westerner in all aspects of life. He stresses the need to accept reality and recognize that the white man has something to offer us. I find this point of view of the playwright eminently sensible. Cultures, languages and skin colours may be different, but such differences do not imply one is superior or inferior to the other. They are merely different. That is all. A sensible human being living in our part of the world will marry the best of the west with the best of the east. Such a synthesis could lead us to moderation, Suddek suggests. Given the jingoism that is raging around us at the present, this sane and sober assessment of our interactions with the outside world ought to be that Suddek offers is indeed refreshing.

In the second episode we are told that glorifying our past and seeking to live in that glorious past will not help us move forward as a country. The playwright tells us that we need those who are aware of our past and those who can envision correctly what our future should be (apata ooney ateetayayai anagatayayai dekama danna minissu/mula amataka nokarapu minussu). He goes on to implore that we re-learn our ancient indigenous tradition of medicine, our ancient dance, folk poetry, Pali and Sanskrit, thereby suggesting that what is relevant and good of our past for our future prosperity must be valued and retained. But, at the same time, we should learn to move with the times and take what is good from outside our own culture also. We need to take not only paracetamol but some kotthamalli as well to cure a headache, the play suggests. We must know both our aga (end) and mula (beginning) if we are to survive and prosper. History is not uni-dimensional but a very complex process. History can often be falsified to suit narrow purposes as has been done in the past. Selective history is also dangerous and injurious to human progress. Therefore a correct reading and conceptualization of history is a crucial responsibility we have as citizens. We should be mindful of deliberate distortions of history by manipulative and unscrupulous others. Suddek urges us to deliberate on these key issues, examine everything carefully and subject all to our critical judgement before arriving at our own conclusions. (Ehi passiko/pacchattang vetitabbo) is a key message that Wickramaratne conveys to us through his play. And this is a salutary message, especially for today, when we seem to be losing our ability to express dissent calmly, rationally and non-violently. Time was when earnest and passionate debate was possible in our society without recourse to physical violence. Suddek seems to be urging a return to those halcyon times of the past.

I found the third episode of Suddek most compelling and riveting- -both in terms of content and acting as suggested above. The female character (striya) who addresses us talks of fair play and justice (sadaranatvavadaya). She starts by telling us that we are familiar with socialism, democracy and fascism but not with sadaranatvavadaya. The latter is a concept that is applicable to all societies, be they in the east, west, north or south. It is a concept that is universally valid, for all human beings respond naturally to fairness and justice. She (the striya) deplores stereotypical images of men and women. She suggests that all should be treated as equals. Each human being regardless of his or her gender has his and her own strengths. We must combine these separate strengths and achieve a creative synergy for our own betterment. It is this character’s and the playwright’s intention to convert all of us into believers in fairness and justice to all (sadarnatvavadaya). In the process of expounding on this theory of fair play, the playwright seeks to debunk the conventional approach to women and romantic love. At the end of the day, all of us- – men and women – – are vulnerable human beings. We men and women are, as is the case between westerners and easterners, neither superior nor inferior to one another. We are merely anatomically different. If we combine the feminine with the masculine, we could be stronger human beings.

At the end of the play, we are led to believe that we are all one. Whites, non-whites, authentic or fake historians, men and women are all vulnerable human beings. If we avoid extremes, are moderate in our views, and speak our truth quietly while respecting the truth of others, we could strive to make this world a better place. This is the positive I gathered from Suddek Oba Amatai. It is most definitely a play that makes one think. It is a piece of theatre that must be watched by all those who value freedom of expression and constructive criticism. It is a play that must be seen to be believed. It is not easy to express in words the impact Wickremaratna’s fine dramatic creation has on us. So I urge you to see Suddek for yourself and make up your own mind about the ideas it seeks to express. I liked very much my encounter with Udayasiri Wickramaratne’s wonderful play. And I look forward to see him go from strength to strength in our theatre scene.