The title is inspired by the article Are Chinese Telecoms Acting as the Ears for Central Asian Authoritarians? published in Eurasianet.org, examining the probable role of Chinese telecoms firms, notably Huawei and ZTE, in espionage and surveillance. The article notes that both ZTE and Huawei have signed contracts worth tens of millions of US dollars with governments in Central Asia, not known for their democratic credentials. The article also flags an on-going US congressional committee probe into the two companies in particular, and how the telecoms products (like USB dongles) and possibly even services (including underlying network technologies and infrastructure) aid espionage. As the article avers,

Over time, authoritarian-minded Central Asian leaders have come to appreciate cooperation with Chinese telecom firms as a useful means of bolstering their authority, rights advocates assert. Some civil society groups argue that Huawei and others are willing to “assist the Turkmen government in monitoring cell phone and internet use in exchange for lucrative deals.”

As the article also notes,

US legislators have expressed concern that Huawei and ZTE act as front companies for the Chinese government, and represent a grave “cyber-security threat.” The chairman of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, Michigan Republican Mike Rogers, asserted during a congressional hearing last October that China is engaged in the “brazen and wide-scale theft of intellectual property from foreign commercial competitors.”

“Attributing this espionage isn’t easy, but talk to any private sector cyber analyst, and they will tell you there is little doubt that this is a massive campaign being conducted by the Chinese government,” he added.

It is worth noting that major telecoms provider in Sri Lanka have multi-million dollar contracts with ZTE and Huawei. The very dongle used to upload this story, on Etisalat, is made by Huawei. In fact, the overwhelming majority of mobile broadband internet access devices sold in Sri Lanka by Mobitel, Dialog Axiata, Etisalat and Airtel are made by either ZTE or Huawei. And if one looks at the value of contracts signed by telcos operating in Sri Lanka with these two companies, it dwarfs the investments made Central Asian countries as noted in the Eurasianet.org article. The largest investment noted there is from December 2006, when “the China Development Bank (CDB) gave a $70.6-million loan to the Tajik-Chinese mobile operator TK-mobile for new equipment purchased from ZTE”.

In June 2011, it was reported that “Sri Lanka Telecom (SLT) has awarded a long-awaited LKR3 billion (USD 27 million) fibre-optic network rollout contract to China’s ZTE Corp as part of the national ‘i-Sri Lanka’ project”. A month earlier it was reported that “Mobitel signed an agreement with the country’s Board of Investment for equipment import duty exemption on its LTE network deployment in partnership with another Chinese vendor, ZTE”. A Press Release on these investments by ZTE notes,

“ZTE’s SDR-based Uni RAN and ETCA/T8000-based Uni Core solution could support products of different platforms such as CDMA, GSM, and LTE. With this solution, Mobitel was able to use just one access network and one core network (RAN & Core) to realize network expansion and seamless evolution. In terms of future network upgrading, only a single baseband processing board is needed to be added or replaced, with the remaining components being realized through software upgrades. This feature will ensure smooth evolution and maximum reduction of TCO.”

When the marketing and technical gobbledegook is unpacked, what emerges is a degree of lock-in to ZTE’s products and services. While this is purported to be cost-effective over the longer-term, it also suggests a reliance on ZTE’s network infrastructure, products and services, which includes, as noted, software upgrades. Media reports also note that SLT’s ADSL infrastructure is underpinned by Huawei technologies. In September 2007, it was noted in the media that “Indian telecom firm Bharti Airtel has signed a 150-million-dollar deal with China’s Huawei Technologies to set up a mobile phone network in Sri Lanka”. The same article notes that this network infrastructure will support “second- and third-generation mobile services” of Airtel in Sri Lanka. In May 2011, it was reported that the two largest mobile telcos in Sri Lanka, Mobitel and Dialog, were basing their 4G/LTE infrastructure on ZTE and Huawei, respectively. A year earlier, in 2010, media reports suggest a big investment by Dialog Axiata in Huawei technologies to improve its network operations. In 2005, media reports in China note a USD 40 million contract to “supply equipment to Lanka Bell for a CDMA wireless local loop telephone network system and fixed wireless terminals to take telecommunications to rural Sri Lanka”.

Chinese investment in Sri Lanka’s telecoms infrastructure is so pervasive that it prompted a US diplomatic cable on it, by the Embassy in Colombo. Marked ‘Confidential’, the report from December 2009 notes,

Huawei Telecommunications, a Chinese owned corporation, has worked diligently to corner the telecommunications infrastructure market in Sri Lanka. Huawei maintains a 33% sector share of existing infrastructure maintenance. Alcatel-Lucent and Ericcson are the two other major competitors, and each has a 33% sector share of existing infrastructure maintenance. Another Chinese company ZTE has a tiny 2% marker share. Huawei Sri Lanka is expanding aggressively into the new infrastructure market in the North and East, where they own more then 75% market share. Alcatel-Lucent and Ericcson are not major players in the new infrastructure market, and they seem disinterested in increasing their market share.

The cable goes on to note,

The Huawei General Manager for Marketing and New Development recent advised us that Huawei hopes to have more than 85% of the new infrastructure market by the beginning of 2010, as well as a larger share of the existing infrastructure maintenance market… No other competitor comes close to matching the breadth and width of Huawei’s operations in the country. Huawei works with all Sri Lankan fixed line and mobile service providers. It has a monopoly on support to Dialog Mobile and Mobitel 3G infrastructure…

Huawei equipment is sometimes suspect and the quality of their work is often questionable. Quality concerns do not seem to be hindering its business model. Some have speculated that Huawei has been assisted by the Chinese Embassy, but we could not confirm whether these suspicions are well founded.

In addition, Huawei,s rise has also bee helped by the excellent relationship between the Sri Lankan and Chinese government. Huawei Sri Lanka’s robust business presence and significant market-share is in keeping with the Chinese outlook to involve itself in all important facets of the marketplace. If Chinese involvement in Sri Lanka is indeed strategic, and it likely is, Huawei’s success is a win-win for China.

Wikileaks cables also suggest a concerted effort, backed by China’s Politburo, to hack into key computer systems, as “part of a coordinated campaign of computer sabotage carried out by government operatives, private security experts and Internet outlaws recruited by the Chinese government”. China’s approach to and regard of human rights is a matter of public record. What is less evident is the means it appears to go to in order to clamp down human rights activism and advocacy. As Google notes in late 2010, China had routinely targeted its platforms and products used by human rights activists, both in the country, and outside. Though first flagged by Google, Operation Aurora, as it has come to be called, is incredible in its reach, and sophistication. As the Guardian notes in August 2011,

Dozens of countries, companies and organisations, ranging from the US government to the UN and the Olympic movement, have had their computers systematically hacked over the past five years by one country, according to a report by a leading US internet security company. The report, by McAfee, did not openly blame any country but hinted strongly that China was the most likely culprit, a view endorsed by analysts.

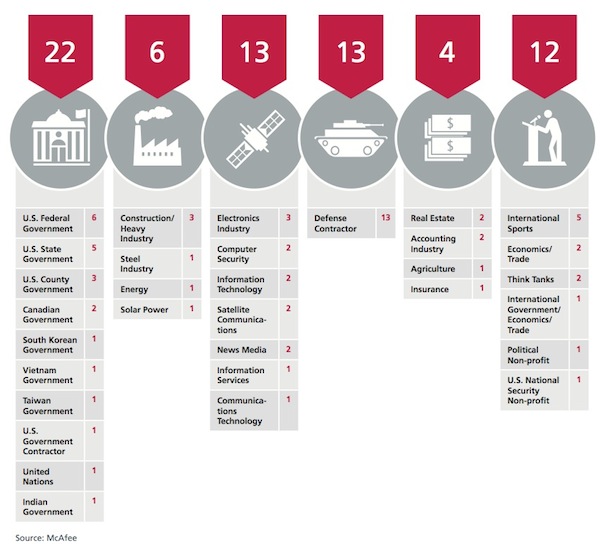

As the report referenced in the Guardian article by McAfee notes, 32 unique organisational categories, across many countries, were compromised as a result of this hacking.

The report generated renewed interest in APTs (Advanced Persistent Threats), which McAfee describes as a modus operandi of hacking that is “motivated by a massive hunger for secrets and intellectual property”, over the long-term.

The Eurasianet.org article stresses that “allegations against Huawei and ZTE are almost impossible to prove”, yet notes that “the United States is not the only country to have misgivings about Huawei, a firm founded by Ren Zhengfei, a former engineer with the People’s Liberation Army”. Questions for Sri Lankans arise from our reliance on Chinese network infrastructure to generate, archive, exchange and disseminate content related to, inter alia, our intellectual property, innovation, human and national security – within Sri Lanka, and with friends and partners around the world. It is doubly dangerous for human rights activists, whose communications could be compromised at a very deep network level, in addition to specific surveillance tools and platforms that can be added retroactively to existing network infrastructure, the likes of which a Wall Street Journal investigation from last year has a positively frightening account of.

At a time when China’s portfolio in Sri Lanka’s economy is growing exponentially, questions over the bona fides of its massive investments in our national communications networks won’t go down well with the Chinese or Sri Lankan governments. ZTE and Huawei have themselves responded to the US Congressional investigations into their operations, with the expected repudiation of all the charges of espionage. Concerns over their operations in Sri Lanka will no doubt be taken to be those coming from quarters who are anyway opposed to government, and scoffed at by all the Sri Lankan telcos themselves. Yet the issue is more than just of deep concern for the dwindling dissent within the country, and the few human rights activists who dare speak out against the regime. The communications network infrastructure in question connects us all, irrespective of any kind of party political, ethnic or other identity and geo-physical based divide. It is the DNA of our country, and how we engage with domestic challenges as well as global opportunities. It may be only of concern to a few today, but the implications of possible network intrusions, that can go undetected for years and the full scope of which may never be accurately known, affects us all.

Perhaps the example of the Trojan Horse – seen overwhelmingly as a gift, but with deadly consequences – is apt to recall.