Image courtesy World Bank

The elderly, usually grouped into those over 60 years, are often looked at as a vulnerable or dependent group in society, sometimes even as a burden. How reasonable is it though to make this generalisation? Those older than 60 years are, for some purposes, disaggregated as the ‘young old’ (60 to 74 years), the ‘old’ (75 to 80 years) and the ‘old old’ (over 80). Within this group there exists a wealth of knowledge, skills and capabilities, along with varying degrees of willingness to participate in society. In reality all older people do not stop working and contributing to society when they turn 60. Should the elderly be allowed greater freedom and opportunity to participate in society if they so desire and how can we make this possible?

Do labour force trends matter?

Elders continue to participate in economic activities into the later years of their life. As Vodopivec and Arunatilake (2008) suggest labour force participation trends have remained constant since at least the early 1990s, with over 50% of men between the ages of 60-69 years participating as compared with less than 20% of women in the same age category. The 2009 Labour Force Survey undertaken by the Department of Census and Statistics (DCS) reveals that those who continue to work despite their age are mainly self-employed in the informal sector, either as skilled or full time casual workers. Both men and women are likely to engage in agriculture, manufacturing and the wholesale/retail sectors. In contrast, public and private sector employees do not seem to continue working after retirement.

Determinants of labour force participation

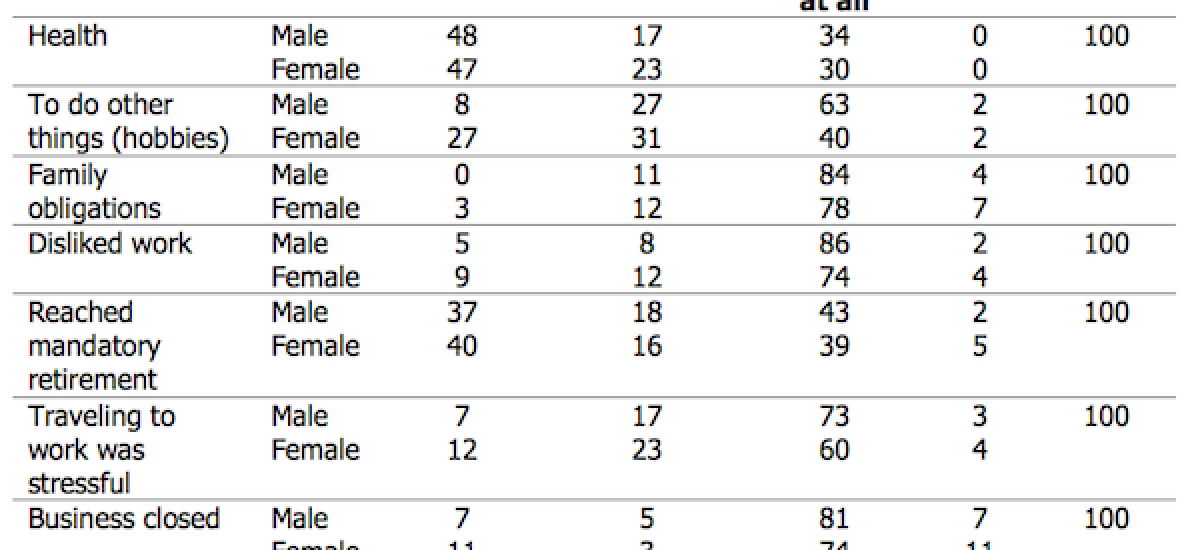

Lower wages and other economic needs in the informal sector tend to ensure the continued engagement of elderly employees. As a World Bank study notes, deterrents to this phenomenon are likely to come mainly in the form of health issues that have caused both men and women to withdraw from work completely. The lack of adequate safety nets (such as a universal pension) and insufficient family support are also likely to extend the age of complete withdrawal from informal sector work. Reaching mandatory retirement is another factor that results in complete withdrawal.

Therefore these trends show that older people do continue to participate – whether it is for reasons of economic security or a desire to continue being productive and engaged.

What is meant by being productive?

Traditional definitions of productivity refer to the production of goods and services in terms of the quality and quantity of inputs (labour, equipment, capital) to produce an output (as defined by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development). Standard calculations of productivity are from an economic perspective and deal with contributions to economic growth. This discounts or ignores ‘non-productive’ work including home-based activities. This too, is likely to be a significant loophole by which issues in relation to the elderly can be easily missed; especially when considering their contribution to household wellbeing and security, as well as towards the local community.

Contribution of the elderly to household wellbeing

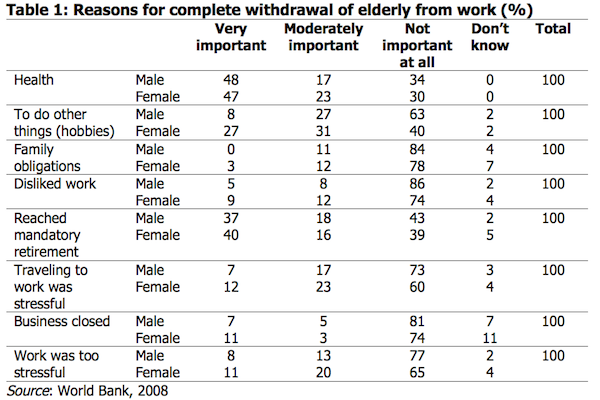

In an attempt to capture their contribution towards household wellbeing the World Bank study indicates that approximately 80% of Sri Lanka’s elderly live with extended families. Many over the age of 60 and with at least one child participate actively in child care, while even those in their 80s, although to a lesser extent, continue to be involved, thereby reducing the financial burden of child care services for income earners. Not surprisingly several elders (albeit in relatively smaller percentages) have been found to be the source of transfers to their adult children in the way of money, property, food and other material benefits.

Table 2: Elderly providing transfers to adult children within the previous 12 months (%)

| Type of transfer |

Percent providing |

60-69 |

70-79 |

80+ |

| Money |

6.7 |

6.7 |

5.5 |

5.2 |

| Housework help |

17.8 |

18.9 |

18.5 |

11.0 |

| Food or material goods |

8.1 |

11.5 |

5.9 |

0.9 |

| Child care |

45.9 |

46.1 |

50.5 |

29.3 |

Note: Sample is elderly with at least one child by birth

Source: World Bank, 2008

Consider the case for households where both parents need to work for economic reasons and have to hire or pay for day care services. This would require that a portion of their salaries would have to be spent on ensuring that their children are looked after. In addition, especially in urban households, external support is sought for domestic help. There is very little quantified evidence, but it can be hypothesised that some amount of that income is saved if the older generation are willing to assist in situations where they are physically able to do so. It also can have plus factors that are less easy to quantify. The greater sense of security in having a resident family member attend to childcare and household chores rather than delegate those responsibilities to an outsider is one such example. The reinforcement of traditional care systems would be another plus factor.

What are the benefits of remaining productive, if possible and desired?

Besides reinforcing their ability to live independently, the mental satisfaction, which accompanies being productive should not be underestimated. This would be a much needed remedy to the findings from Andrew, Mitnitski and Rockwood (2008), which states that the elderly may experience feelings of loneliness, helplessness and worthlessness due to the lack of social support, social engagement and control over their lives. In terms of having control of their lives and not being a burden on others, one elder said:

‘This is the time in a person’s life where things take a turn for the worse (ava paththakata yanne), so we need to be strong in character and be able to manage on our own without being a burden to our children’. Another added ‘Our members are strong willed and do not want to rely on their children. We want to be independent. We want to have mental satisfaction’ (Focus Group Discussion, Senior Citizens Committee – Ambalantota).

The benefits of the elderly staying involved and productive, undoubtedly extends to broader society as well. Elders could continue to contribute to the regular workforce by sharing their knowledge and experience, as well taking on advisory and mentoring roles and serving as retired professionals.

Cross-empowerment in the way of facilitating elders to help each other also warrants deeper exploration. This approach could cover a broad spectrum ranging from lobbying for rights to supporting elders who are vulnerable. For example, existing frameworks for voluntary social work could be strengthened fostering social engagement and community development through elders’ committees.

Members of the SCCs shared the sense of satisfaction and achievement they experience through social engagement.

‘We have got a lot of mental satisfaction from this – otherwise we were just at home and this has increased our interactions’

‘Earlier we had no one, we felt isolated and alone now we are strong; we can stand on our own’

‘We have helped families that are having problems’

‘Now we know our rights – if children don’t look after us’

‘We have learnt to be more efficient, learnt new skills (home gardening)’

Source: Focus Group Discussion, Senior Citizens Committee – Mirissa

Does the policy framework support involvement of elders?

The Protection of the Rights of Elders Act of 2000 emphasises the rights of older people to receive optimal care from their children. It is indeed creditable that measures to counter willful negligence are in place. The activities supported under the Elders’ Secretariat of the Ministry of Social Welfare also extends to getting priority treatment in places such as banks and hospitals as well as discounts on medicines and bus fare etc, with the elders’ Identity Cards.

The principal function of the National Council for Elders as stipulated in the Act is ‘the promotion and protection of the welfare and the rights of elders in Sri Lanka and to assist elders to live with self respect, independence and dignity’. Among its other functions are advising the government on the promotion of welfare and rights of elders and recommending programmes to the government and other appropriate bodies to strengthen the family unit based on the traditional values of Sri Lanka.

As the provisions show, the tendency is to view elders as a vulnerable group with a focus on improving their wellbeing. This is not an angle that is disputed or seen as unnecessary as there are many elders who require this support. However, there is limited provision in the Act to facilitate the active involvement of the elderly in society.

Bringing in the rights perspective

HelpAge International’s work highlights the universality of this matter. It raises the perspective of the rights of the elderly to work, a right everyone else has. This right has been recognised by many human rights instruments as being fundamental to personal development and social and economic inclusion.

Should rights frameworks go beyond protection and support elements? HelpAge International claims that although governments are obliged to include older people in national policies and programmes on work, few programmes in reality address older workers’ needs and protect their rights. Inclusion, accordingly, should entail recognition of the difficulties that older workers face in finding and keeping jobs. This fact has been acknowledged explicitly by the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which stressed the need to prevent age discrimination and the importance of upholding the rights of older people to form and join trade unions. Safe working conditions and the employment of older workers in circumstances that can make best use of their skills and experience are recognised as particularly important for older people.

Final thoughts …

In summary, it is important to consider elders as a group as diverse as any other segment of society rather than as a homogenous social entity. Older people have individualised capabilities in addition to the often addressed ‘wants and needs’. While measures put in place to support the vulnerable amongst the elderly deserves commendation, the fact that there is a wide range of expertise and skill among them that can be used as a resource for the benefit of society as a whole, should also be acknowledged. Not forgetting the importance of free will in the elderly, the levels of contribution could be customised according to the individual’s degree of motivation to participate.

Given Sri Lanka’s ageing population demographic, it would be timely to consider how we can maximise on the positives of the elderly. Changes, be they legislative or attitudinal, will be necessary to create a culture of inclusivity, which would be conducive to fostering elderly participation in society. It is also important to set these changes within Sri Lanka’s cultural context of extended family that supports and values the contributions our elders make in households and families around the country.