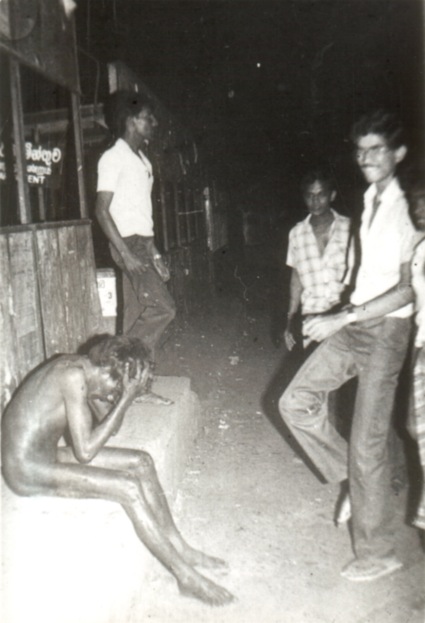

Photo by Chandragupta Amarasinghe

ONE

What happened in mid-1983 and in the last week of July 1983 was obscene, a monumental atrocity, a disaster for Sri Lanka. In a context marked by the push for self-determination by the principal forces representing the Sri Lankan Tamils and an armed underground insurgency involving restive youth in the extreme north, government functionaries and elements of the ordinary populace took it upon themselves to unleash punitive attacks on Tamils living in the Sinhala-majority areas in the south. In both the towns and in several parts of the supposedly idyllic countryside Tamils were killed, assailed, maimed, terrorized and forced to flee or hide.

It was not an ethnic “riot,” a term left over from the British Raj and one that covers a wide array of affrays (inadequately, of course, because of its wide sweep). Nor was it a holocaust. It was something in between in the lexicon of assaults: a pogrom.

Apart from the immorality of the acts, whether viewed singly or collectively, the consequences were quite counter-productive even in terms of the thinking that inspired the various stirrers and perpetrators. The attempt to “teach the Tamils a lesson” backfired. The militant movement for separation gathered thousands of new Tamil recruits and a rejuvenation of commitment among most SL Tamils, as well a wave of support in international quarters. Sri Lanka also received pariah status on the world stage.

TWO

One Easter weekend two years later I was on a bush walk in the Gammon Ranges of South Australia and woke up early. I did not stir out of my sleeping bag because it was bitterly cold and pitch black outside. My thoughts were as lucid as the night was black. They were lucid ‘black’: in my fantasizing mind’s imagination I lined up the whole of the UNP Cabinet and mowed them down with a machine-gun.

This because they had ruined Sri Lanka as I knew it – for it did not take a rocket-scientist to realize that an absolute disaster had been consolidated by the events of July 1983. The country, my Sri Lanka, was, as local slang would say, “now down the pallam” — and going, going down pallam, pallam yet further.

This utopian act of retribution by my hands there in the Gammons that dark night was not constrained by personality or friendship. I knew Lalith Athulathmudali as acquaintance and had participated in official dealings with JR Jayewardene in the course of my archival operations. No exceptions were made in the catholic sweep of my imaginary sten-gun.

This was a form of paligänÄ«ma (revenge, vengeance) in mind’s wish. I must be Sri Lankan to the core because Sinhalese, Tamils and others share this tendency in seemingly equal measure (read Obeyesekere on murder by sorcery practice).

THREE

The focus on the UNP in my act of fantasia is a simplification. Let me render the tale more complex. The responsibility for the atrocities that July were/are not restricted to segments of the UNP. Grapevine stories suggest that Sinhalese from all political parties, all religious persuasions, all classes and walks of life participated in the acts of instigation and acts of assault. Women too stirred the assailants and were among the looters. Looting, of course, was opportunistic and could even include Tamils from slums and shanties targeting the homes of well-to-do or shops broken down and open.

Stirrers and assailants probably added up to a minority of the stunned Sinhala population writ large (otherwise the kill-count would have been much larger than the estimated 3000 odd). But – an important “but’ this – there were some Sinhala non-participants who remarked aloud that the “Tamils deserved what they got.” These were (are) also many apologists among those on the sidelines of action.

A particularly intriguing category of persons/families are the Sinhalese who provided refuge for Tamil neighbours and friends, or arranged for their protection, while yet instigating the pogrom. I have at least three anecdotal tales marking such instances, two of them UNP cabinet ministers. So here we see ambiguous categories of action, no less obscene and atrocious than the assailant work of the Tamil-haters.

Such stories of Sinhalese activism in generating Black July must be balanced by the many anecdotal tales of horrified Sinhalese, Burghers and others who assisted Tamils-in-strife, and those who worked tirelessly in the refugee camps. And we must surely salute the courageous few who rescued Tamils on the road from Sinhala killers and those who stood firm in their little streets and withstood bodies of assailants intent on battering mayhem against Tamil householders therein. All this information, I add, is based on first-hand or second-hand tales lodged in my memory bank and he occasional first-hand account in print.

FOUR

As yet we do not have a comprehensive, or even a near comprehensive, study of Black July. Here, again, the pogrom of July 1983 cannot be viewed in isolation. There were attacks on Tamils prior to that. Apart from the relatively minor instances in 1956, 1970, 1981, the two most significant were the mini-pogroms: those of mid-1958 and mid-1977. The former has only attracted brief or inadequate reviews (Vittachi, Manor), while the latter in August 1977 is largely unexplored terrain as far I am aware.

Though unexplored in depth by analysts both clearly remain inscribed in the minds of Tamils who were threatened or victimized by these acts of atrocity; while anecdotal tales of harrowing suffering would have circulated across Sri Lankan Tamil networks – and also among the Malaiyaha Tamils of the plantations who were victimized in 1977. July 1983 compounded these tales thousand-fold.

Photo by Chandragupta Amarasinghe

FIVE

Clearly, none of these atrocious events can be reviewed in isolation. They have to be set within a study of the complex political processes since 1931, a study that takes note of the political economy and social developments that interlaced with the structured political processes to gradually sharpen the competition between Sinhalese and Tamils to the point of no compromise. So, the story is complex and cannot be summarized briefly except, perhaps, to say it as a tragedy.

Arguably, albeit speculatively, if Sri Lanka had received proportionate representation in 1947/48 instead of a Westminster system of first-past-the-post, then, the political chasm may not have sharpened to the degree that it did, As I have contended long ago, the Westminster scheme within the peculiar demographic distributions in the island rendered it difficult for Sinhala-politicians to give concessions – the problem was political/structural, though a lack of ideological vision did exacerbate matters (see my article in Modern Asia Studies 1978 reprinted in Exploring Confrontation, 1994).

While agreeing thus with the several Sinhala scholars who have attributed the fundamental blame for our present dilemma to the Sinhala peoples and their polity over the recent decades, a proviso must be entered. At various points of time the Tamil political leaders, from GG Ponnambalam to Chelvanayakam and the Federal Party personnel, seem to have contributed their mite to the sharpening of conflict – through rhetorical excess as well as machination. This, let me note, is an impressionistic comment and not developed clearly in any of my writing.

SIX

Thus contextualized, we can return to the present situation. The “1956 ideology” was rejuvenated during the last Presidential campaign and reigns again. “Ape Anduva” is commanded by four brothers who tell the Sinhala masses what is good for them. It is a new version of the cakravarti figure of old, the “Asokan Persona” as I once described this figure of the modern populist era (also in Exploring Confrontation). While presenting an amiable, moral face, the decision-making is top-down in its flow and provides the best returns to those subordinates who take a propitiating stance, a stance that thereby reproduces the top-down patronage-authoritarianism that is already in place. But one should not forget that this recrudescence of currents from “the 1956 revolution” has been made possible by the LTTE-cum-complicit-Tamil role during the last presidential elections, and by a longer history of LTTE obduracy and duplicity. This truism does not make this picture any less palatable.

This is to digress. Let me conclude by linking back to the themes arising from the “1956 ideology” associated with Sinhala cultural nationalism and its outcomes in May-June 1958 and July 1983 (see pictures). It is important for those attached to the Sri Lankan polity in its multi-ethnic form and its desire to appease those Tamils who are still Lankan in spirit that BLACK JULY should not be obliterated from memory.

That is what some Sinhalese – alas, I have no statistics on their numbers or proportions – desire. Recently in a cyber-net exchange which embraces me (unsolicited) one Bodhipala Wijesinghe asked a moderate Tamil gentleman Kathirevelu searching for compromise this question: “Tell me, in what way have the Tamils been bullied?” — truly an amazing question that, to my mind, revealed a monumental blindness. Wijesinghe, at least, asked the question with a desire to learn from Kathirevelu albeit with shutters already half-way up. Not so other obdurate Sinhala chauvinists: they remain in denial. Thus a few years back HLD Mahindapala wrote a review of politics in recent decades in his usual acid style in which the events of July 1983 did not receive one mention.

There is a measure of incorrigibility here that is as debilitating as a cause for despair.

A passenger taken out of the vehicle and being beaten up in the anti-Tamil riots of 1958. Photo courtesy Victor Ivan.

For more articles on July 1983, please click here.