May 18, 2009 is a day that showcases division. To some, it is a day of mourning. To others, cause for celebration.

Families in the North and East who commemorate their family members killed during the final stages of the war on May 18 call this day “Remembrance Day”. Conversely, May 19 is known as “Ranaviru Day” and is meant to remember soldiers whose lives were lost during the war.

This year’s Ranaviru Day will be held at Parliament Grounds, and attended by Government representatives.

In contrast, the Remembrance Day events have been repeatedly blocked in the past – including as recently as last year, with the police citing national security concerns.

One year after the end of the war, Groundviews ran a critically acclaimed acclaimed special edition reflecting on whether the absence of war alone meant the advent of peace. It was revealing that in a subsequent edition five years after, in 2009, we were having the more or less the same conversations, asking the same questions.

In 2018, many of the areas where families gather in remembrance have changed.

Mullivaikkal, where the last stages of the war were fought, is symbolically, the site of the main Remembrance Day ceremony this year (Families in Batticaloa also staged organised their own ceremonies).

The following is a comparison of Mullivaikkal in 2009, and again in 2016 (the most recent historical imagery available on Google Earth).

In 2009, the photo shows homes, both inland and makeshift settlements on the beach. The land is dry and barren. Historical imagery captured by Google Earth in 2012, featured on Groundviews found evidence of shelling. In 2016, trees have grown. New homes have been built. The settlements on the beach have disappeared.

Today, whatever may lie buried beneath the sand, the beach is quiet and still from space.

Just over 7 kilometres away from Mullivaikkal, according to Google Maps, is Ampalavanpokkanai. In May 2009, this area was densely populated with people in makeshift tents (every white dot on the map is a shelter). In 2016, unsurprisingly, these temporary settlements are absent – though one or two larger buildings can now be seen.

The Vadduvakkal Bridge causeway over the Nandikadal lagoon acted as a point of crossover from civilians leaving rebel-held areas into government control.

In 2016, large buildings can be seen just past the bridge.

An RTI request from our sister site Vikalpa recently revealed that land in this area was being taken over for a public purpose, for the building of another Navy camp. The Navy also now operates ‘Lagoon’s Edge’ cabanas close to the beach here. The presence of military-run tourism in this particular location has concerned activists worldwide. The large buildings around the bridge in the imagery from 2016 may be installations belonging to the Navy or military.

The Jordanian vessel named MV Farah III was looted by the LTTE off the coast of Mullaitivu and was later used as an operational centre by the Sea Tigers. In the days before the end of the war, the Sri Lankan army captured the territory within which the ship was located. In 2013, the Army sold the ship to a private party, to be used as scrap. Widely photographed after the end of the war, the satellite imagery from May 2009 shows the ship intact, while in 2016, it is almost completely submerged.

Today, only the rusted hull of the ship remains.

From miles above, these spaces appear verdant. Calm. Peaceful. Yet, a closer look reveals that many issues remain unresolved.

For over a year, civilians across the North have been protesting, day and night, for the return of lands occupied by the military. Documenting these protests has been revealing in showcasing on-going militarisation and surveillance, as well as the extreme lengths civilians are willing to go in order to have their lands returned to them. The protesters, as well as journalists and rights activists have been subject to threats, assault and intimidation, as recently as 2017.

The protesters who do persist, and are rewarded with the prospect of returning to their land, face the daunting prospect of rebuilding homes and livelihoods with little to no support from the State.

However, the fact that these protests were not shut down by brute force, and that, in a precious few instances, their dogged persistence was rewarded, gives some cause for hope.

Most recently, residents of Iranaitheevu courageously sailed to the island and reclaimed their land. They have now been given permission to resettle, and promised livelihood assistance. Rights activists accompanying the residents who sailed there recalled a time when the Navy had shot, killed and injured civilians inside Pesalai Church. In contrast, in Iranaitheevu, the Navy listened to the former resident’s grievances and allowed them to stay the night (and eventually, to stay on and rebuild, albeit facing innumerable difficulties by way of fresh water and other basic facilities).

Photos by Vikalpa

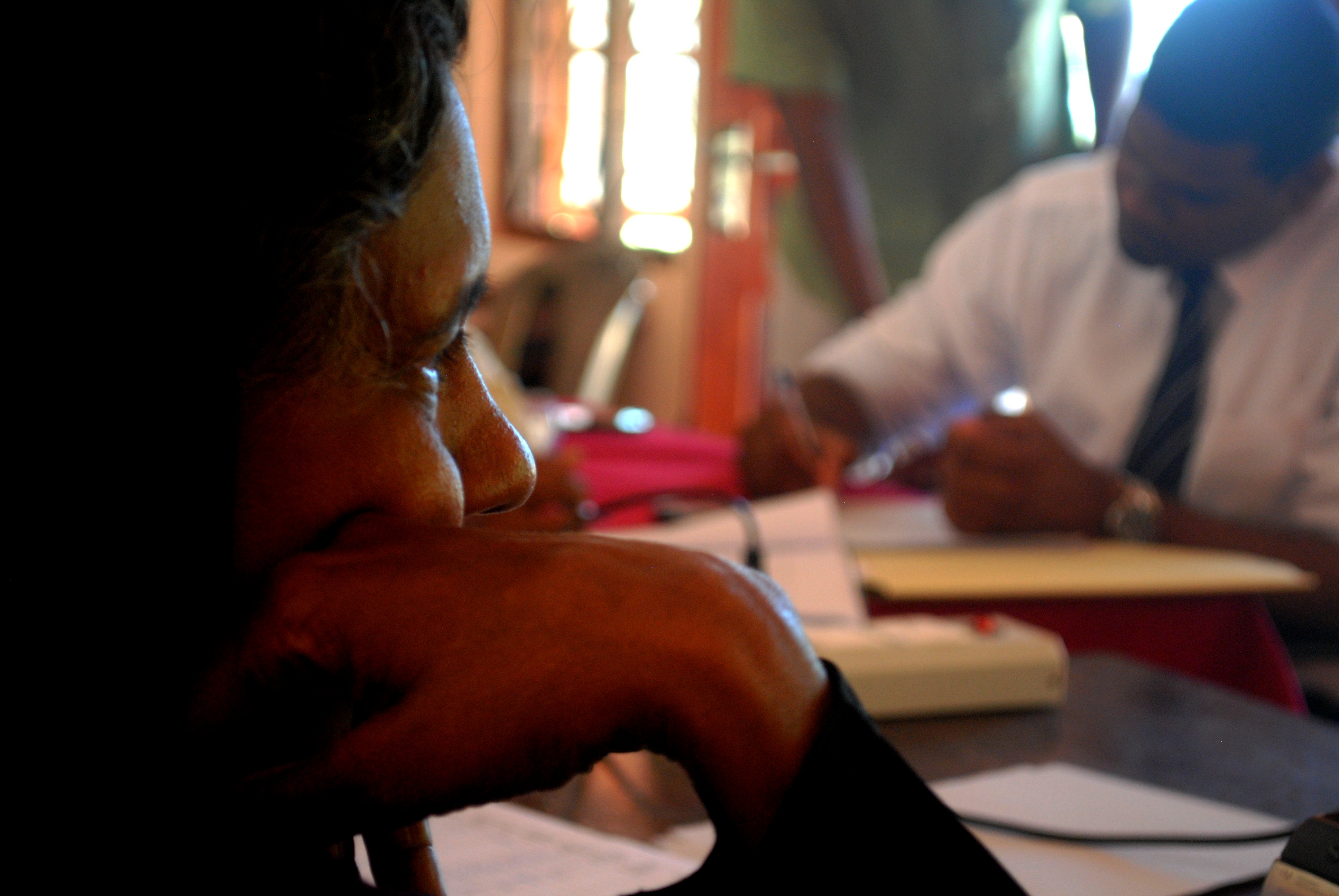

There has been little cause to rejoice, however, for families of the disappeared. They too have been protesting for over a year, quite literally day and night. In response, the Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe went on record saying that the missing are ‘probably dead‘. The gross insensitivity from the State aside, many continue to believe their families are alive, held in secret detention centres. In February 2018, the President Maithripala Sirisena reiterated that there were no such detention centres in Sri Lanka, in response to their repeated queries for answers. Their frustration was apparent as they addressed the newly created Office of Missing Persons (OMP) during their first hearing in Mannar. The road to setting up the OMP has been long and fraught with politicisation. Now that it is established, even members of former Commissions of Inquiry into Disappearances are raising questions about its effectiveness, given the legal and administrative obstacles it faces.

Meanwhile, women and particularly female-headed households in the conflict-affected areas struggle to earn a living. Many of them have seen their education disrupted, limiting their potential to earn a livelihood. Some fall prey to finance companies who offer loans at prohibitive interest rates – plunging them into debt. Many are in urgent need of psychosocial support and counseling.

From a story on gender-based violence in Mannar and Mullaitivu

In this context, the words of Army Commander Mahesh Senanayake in a recent interview with the Hindu are particularly jarring. “We are a victorious army,” he said before outlining his vision of the role of the Army in post-war Sri Lanka. He mentions instilling discipline, ensuring non-recurrence of the conflict, and restoring normalcy. In April, at an event marking the second phase of a housing scheme in Nallinakkapuram that the Army was “able to take back what it granted” to the Tamil people.

Nine years after the end of the war, Sri Lanka continues to debate on who deserves remembrance. During a recent Cabinet news briefing, Government spokesman Rajitha Senaratne drew distinctions between civilians, former cadres and military personnel. The varied reactions to his statement are revealing. President Sirisena tweeted on May 18 about the commemmoration of war heroes, and using the hashtag #victoryday only to hastily delete his tweet after a backlash over social media. His next tweet however, upheld the same distinction promoted by Senaratne.

I express my deepest gratitude to all Sri Lankan war heroes on this National War Heroes Commemoration Day.

— Maithripala Sirisena (@MaithripalaS) May 18, 2018

Many of the questions that were asked a year after the war ended continue to be asked in 2018. Until there is political will to meaningfully address them, they will continue to be asked, every May 18, for decades to come.

Editor’s Note: This post is inspired by a 2012 story by Groundviews, which used satellite imagery released by UNOSAT to uncover the extent of damage wrought in the final weeks of the war.