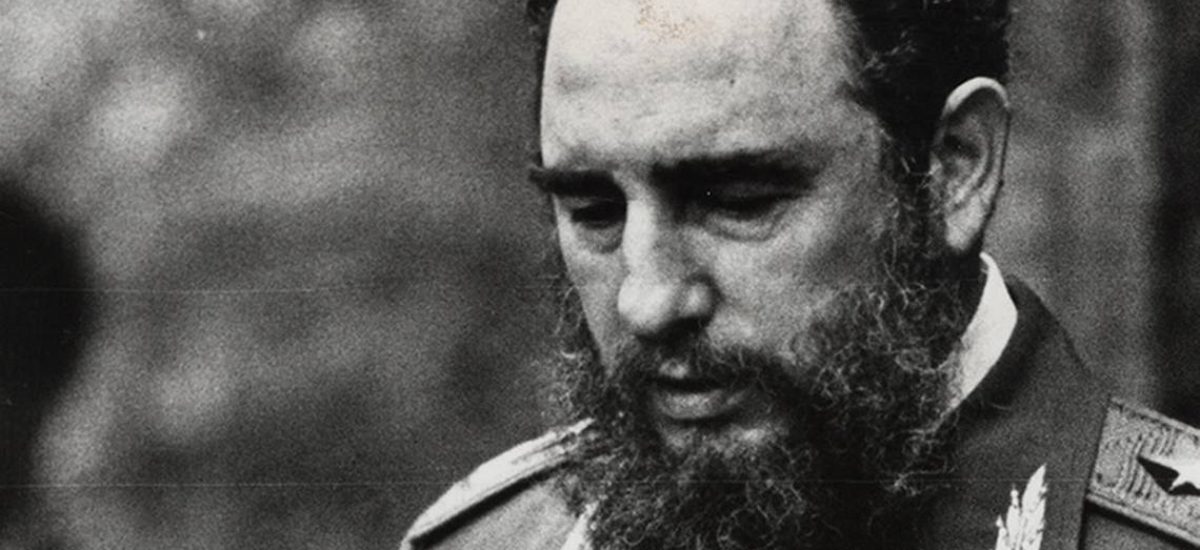

Photo courtesy Miami Herald

“The struggle itself towards the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart.”

Camus (The Myth of Sisyphus)

According to an ancient Chinese musical treatise (written in the second century BCE), when any of the five notes in the Chinese pentatonic scale turns disharmonious, disorder results in human affairs. If all five notes are out of harmony, danger results, and the imminent destruction of the kingdom ensues.

Mao would have deemed such a situation of great disorder excellent. But disorder, though necessary to overcome ossification of conditions, is not always the ally of progress. This is particularly so when religion plays an oversized role in creating disorder.

“If Richard Coeur-de-Lion and Philip Augustus had introduced free trade instead of getting mixed up in the Crusades, we should have been spared five hundred years of misery and stupidity,[i]” Fredrick Engels famously lamented. The Crusades depleted Europe of its men, resources and energies and retarded its progress. Given the more advanced conditions prevailing in the Islamic lands of that time, Christian Europe would have fared better if it sent not armies of warriors but armies of scholars and traders to the Middle East.

An even worse disorder resulted from the Thirty Years’ War, a brutal conflict which pitted Christian against Christian and devastated most of Germany and parts of Central Europe. It involved all European powers and is believed to have caused the death of 4 to 11 million people, either directly or indirectly (through famine and disease). An estimated 20% of the population of German states perished. The only positive consequence of this inane conflict was the diminishing of religious influence in European politics and society.

In parts of North Africa and the Middle East, a somewhat analogous process is underway currently. Religion in general and the Sunni-Shia divide within Islam in particular constitute a decisive factor in the wars currently devastating the region, from Yemen to Syria. If the trajectory of the Thirty Years’ War is anything to go by, the violence and the devastation will not stop until the zeal of zealots is burnt out. And that would take a while. Hopefully, the region will someday emerge from the wars, a little less inclined to kill and die in the name of a creed.

The times are characterised by growing disorder, the kind which retards progress, which forces humans to abandon their gains and retreat into the past, chasing lost paradises. Socialism has failed, Capitalism cannot deliver, and the resulting vacuum is being filled by tribal and religious ‘solutions’. When the incoming president of the waning empire expresses a terrifying willingness to risk a confrontation with the rising empire to prove a point, when in a new reality show which permits murder and rape is about to premiere in Russia, once the locus of the socialist dream, when Aleppo, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world, a living monument to the march towards civilisation is being torn apart by a power-hungry despot and a religiously-insane ‘Caliph’, when climate change is fast reaching the point of no return, it is hard to be hopeful[ii].

Countries need heroes, though only for a time. But the world would always need resistance, this side of an earthly paradise, and never more so when zealots drunk on divine words promise to usher in earthly paradises, founded on the corpses and watered by the blood of ‘unbelievers’. This world needs the unheroic-heroism of a Sisyphus, who neither kills nor dies, but endures, never letting go of the rock, like the White Helmets in Aleppo to the ordinary men and women, braving military beatings and sub-zero temperatures to protest the Dakota Access pipeline at Standing Rock. They may not change the world, but they save lives and improve human condition.

Had Fulgencio Batista not pulled his second coup, Fidel Castro could have been such an ordinary, unheroic-hero.

Imperfect Choices

In 1952, Cubans had been preparing for a normal election to select their next president and their next congress. What they got was a military coup. Fulgencio Batista had come to power the first time in 1933, via the Revolt of the Sergeants. His first rule had been relatively benign. He had retired, lived for years in the US, returned to contest the presidency in 1952 and pulled the coup when faced with defeat. Election was cancelled, constitution suspended and Cuba’s transformation from a flawed democracy into an autocracy, a fief of American business and American mafia, commenced.

At the time of Batista’s second coup, Fidel, a young lawyer, was on the threshold of a career as an electoral politician, contesting a congressional seat from the Orthodox Party. Had Batista not pulled his coup, had Cuba remained a land where people could change their rulers through the ballot box, there would have been no Moncada, no Granma landing, no Fidel-Che-Raul-Camilo revolution.

In History Will Absolve Me, the speech he gave in his own defence at the Moncada trial, Fidel narrated the events which propelled him to launch an armed attack on a military garrison. “Once upon a time there was a Republic. It had its Constitution, its laws, its freedoms, a President, a Congress and Courts of Law. Everyone could assemble, associate, speak and write with complete freedom. The people were not satisfied with the government officials at that time, but they had the power to elect new officials and only a few days remained before they would do so…. Poor country! One morning the citizens woke up dismayed; under the cover of night, while the people slept, the ghosts of the past had conspired and had seized the citizenry by its hands, its feet, and its neck…a man named Fulgencio Batista had just perpetrated the appalling crime that no one had expected.”

Life in the shadow of any empire is hard. Empires begin by preying on their neighbours. This is true from democratic Athens and autocratic Persia in Antiquity to democratic United States in the previous century and autocratic China today. In 2016, and after eight years of Obama Presidency, it is hard to remember how often democratically-elected governments suffered bloody military overthrow in Latin America, because the new empire preferred uniformed despots to be in charge of its backyard, leaders who were free from the demands of democracy and didn’t have to concern themselves about popular opinion.

So the Empire, while practicing democracy at home, turned its backyard into a bastion against democracy, unhappy lands which demanded heroes. The overthrow of Guatemala’s Jacobo Arbenz in 1954 was a turning point in the transformation of Ernesto Guevara into Che. By the time the Cuban Revolution succeeded, the choice in Latin America was not between democracy and its opposite, but between various types of non-democratic dispensations. The fate of Salvadore Allende’s Chile proved beyond any doubt that even in the 1970’s democracy had no chance of survival in Latin America, when an American backed coup forced the country’s democratically elected – and elderly – president to defend his mandate with a gun in his hand, in a presidential palace surrounded by tanks and attacked by planes.

Commenting on Fidel’s death, President Barak Obama said that “History will record and judge the enormous impact of this singular figure on the people and the world around him.” Any judgement by posterity will be imbalanced if it takes no account of the time and place in which Fidel made and defended his revolution – 90 miles away from a United States which was at the height of its military power and interventionist will, a country still invincible and yet to experience the humiliation of Vietnam. That geography and that history played a critical role in deciding Fidel’s choices and Cuba’s trajectory. Had Fidel been in Nelson Mandela’s geographic position and in his time, what choices would he have made? Had the roles been reversed, what would Mandela have done? Both questions would remain unanswered and unanswerable.

What is knowable is what happened. In his Moncada speech, Fidel had mentioned several goals animating his political involvement. “The problem of the land, the problem of industrialization, the problem of housing, the problem of unemployment, the problem of education and the problem of the people’s health: these are the six problems we would take immediate steps to solve, along with restoration of civil liberties and political democracy.” Restoring civil liberties and political democracy remained broken promises, but in some areas such as education and health, Fidel’s success was spectacular, not only in that region or for that time. Those singular achievements draw praise even now, even in places where there’s little sympathy for the Cuban Revolution or little liking for Fidel.

Soviet money helped in enabling Cuba to attain record levels of literacy and a world-class health system, but the critical factor was political will, Fidel’s will. In general, leaders, including democratic ones, are likely to misuse or steal generous handouts by international patrons. Even loans which have to be paid back are squandered. Fidel ensured that some of the Soviet money was used to ensure for his people a living standard higher than anything they’ve experienced in the past, and for a time better than what obtained in many Latin American lands.

Fidel’s nemesis was a United States which wanted an ossified Cuba, ossified the way it was under the second Batista regime. His response in part mirrored this challenge; he attempted to ossify Cuba, the way it was when the Soviet Union was intact and really existing socialism was believed to be a realistic possibility. But change cannot be stopped, and this was perhaps what Fidel meant when he said, “The Cuban model doesn’t even work for us anymore”[iii].

Worse Times

The ancient Chinese musical treatise identifies five calamities which can result from disharmony: disorganisation, when the Prince is arrogant, deviation, when officials are corrupt, anxiety when people are unhappy, complaint when public services are too onerous, danger when resources are lacking. The Cuba Fidel inherited suffered from many of these calamities, and he changed things for better. The dividing line between utopia and dystopia is a very thin one, and often its crossing can be seen only after the fact, when it is too late, politically and psychologically to turn back. Cuban revolution disappointed many of its followers, but it never degenerated into a North Korea. For that Fidel deserves credit. He personified the revolution, but wouldn’t allow the development of a personality cult.

Che didn’t want to rule. By going away from Cuba to die in Bolivia, he managed to prevent his aura and his image to be diminished by the inexorable march of history. Fidel stayed back and ruled. When he died, at the age of 90, there was sadness, but nothing like the grief that would have exploded had he too died young, a hero felled by the empire. But then had Fidel died young, the revolution would have died with him, replaced not by a democratic Cuba, but the Cuban version of Pinochet’s Chile.

In 2010, Fidel had asked Jeffery Goldberg, the editor of Atlantic, to visit Cuba to discuss the Iranian nuclear crisis, and to warn all parties of the need to act with caution to prevent a confrontation. Goldberg asked Fidel about the rather different stance he took during the Cuban Missile Crisis. “After I’ve seen what I’ve seen, and knowing what I know now, it wasn’t worth at all,”[iv] was reportedly Fidel’s reply. His final forays into international affairs were aimed at making peace. He urged caution on the trigger-happy North Korean leader and helped end the longest violent conflict in Latin America. Fidel and Hugo Chavez were the initial facilitators of the Columbian peace process, playing a behind-the-scenes role in getting the two sides to talk to each other.

If Fidel began his long political career in a time of global hope, he ended it in a time of global despair. In his final speech to the Cuban Communist Party in April 2016, Fidel Castro warned that humanity, like dinosaurs, can be wiped off the face of earth, either through a nuclear confrontation or through climate change. If in his youth, Fidel was a Promethean hero, in his old age he was more like Sisyphus. He acknowledged the crushing truths (at least some of the time) but still bore his rock. That attitude and spirit fit these times, the times in which he died, the times we must live in.

[i] Letter to Franz Mehring – July 14th, 1893

[ii] https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2016/dec/15/russian-reality-tv-show-allow-rape-murder-game2-winter

[iii]https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2010/09/fidel-cuban-model-doesnt-even-work-for-us-anymore/62602/

[iv][iv] https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2016/11/fidel-castro-obituary/508805/