When I first travelled to Sri Lanka in the nineties, the country was still recovering from the shocking violence of mass disappearances in the late eighties.[1] It was difficult for people to talk about this period and sometimes friends would close down, the memories were simply too raw. It was only years later that I learnt a close friend had lost half his school friends in 1989 – an event so shocking and so far from my own teenage experiences. As I started to develop an awareness of the complexities of Sri Lankan history it was Sri Lankan artists that prompted me to explore what was hidden from plain view.

I had the privilege of attending exhibitions in Colombo and enjoying exchanges with some of the artists who went on to launch the ‘No Order Manifesto’ (1999). One artist whose work stood out is Chandragupta Thenuwara whose Barrelism series played with the ubiquity of war culture. The idea of surface and hidden meanings was explored through camouflage brushstrokes that hinted that things were being made to vanish – alluding to a trend of tragic disappearances and unlawful killings. In this period art emerged that seemed overtly interventionist using art to surface histories of violence.

Many of the artists that were at the forefront of the ‘90s art trend such as Jagath Weerasinghe acknowledged that violence had touched them personally. His exhibition ‘Yatra Gala and the Round Pilgrimage’ was hosted by the Heritage Gallery. On entering, the visitor had to walk across dry rice encouraging an interaction with the installation. The exhibition took the viewer on a journey across Sri Lanka with a mother looking for her son. She visited Suriyakanda and other mass grave sites creating an alternative pilgrimage. The artist notes:

“The idea for this work first occurred in my mind, in February 1996, when I was at Embilipitiya, a village in the south of Sri Lanka, organizing a ceremony for a group of parents, whose children had disappeared and been murdered in 1989-90 at torture camps in Embilipitya. The ceremony was organised as part of the ‘Shrine of Innocents’ monument which is being built to commemorate these lost children…To this ceremony most of the mothers came wearing white sarees and holding a picture of their lost child. These women reminded me of mothers going to temples with flowers, held in their hands. Their white sarees made it so severe a feeling. Instead of flowers, now they are carrying the photograph of a child who is murdered.”

Sri Lankan society has a tragic history of tens of thousands disappearances. This includes enforced disappearances by the state as well as abductions by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and other paramilitary groups. The shadows of the disappeared leave their DNA traces in a number of mass graves across the country. What is also profound is the visceral impact their loss and the lack of ability to commemorate their bodies properly leaves on their loved ones.

Across 2014 and 2015 the Women’s Action Network (WAN) engaged in a project that aimed to value the lived experience of disappearances. They wanted to find a way to convey the anguish of losing children and worked with a group of mothers to create an exhibit. The result of the interactions were saris carrying silhouettes of a number of mothers who wrote the names, place and location of the disappearance of their child. Linking local voices to global advocacy the saris travelled the world and Amnesty International hosted a vigil for the disappeared in Geneva in March 2015. The saris made by 22 affected women from Mannar and Batticaloa were held aloft by Sri Lankan and international advocates during the 30th session of the Human Rights Council. As the material unfurled outside the Palais de Nations it was a potent symbol of families’ endless quest for justice.

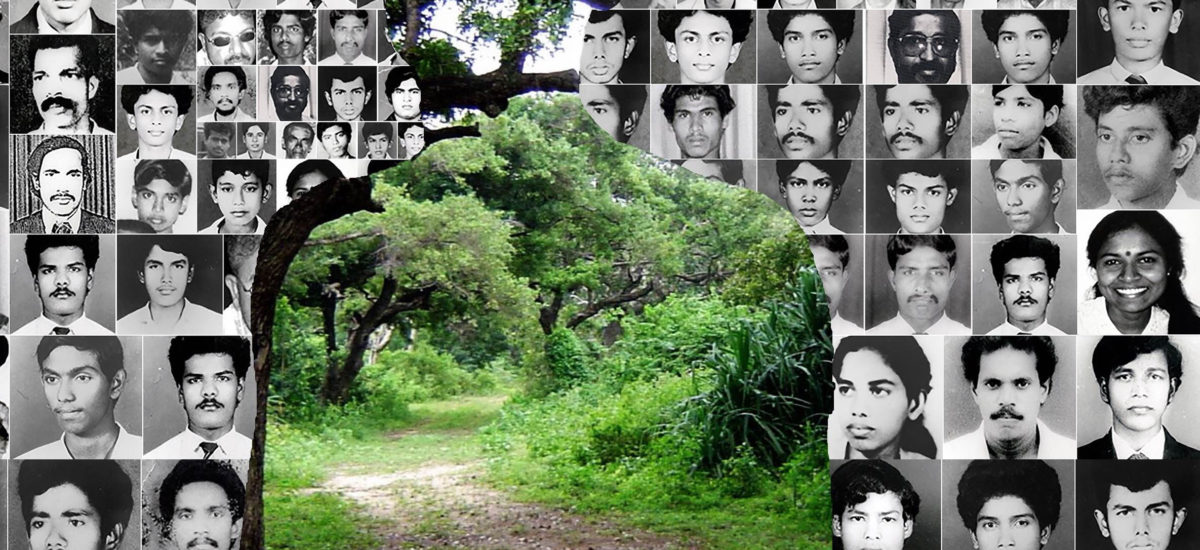

Over the decades many families of the disappeared have shared statements about their missing children with Amnesty International. Earlier in the year on a visit to the Sri Lanka archives at Amnesty’s International Secretariat I came across an old manila folder from the late 80s labelled ‘Disappearances’. Inside I found thumbnail black and white photo after photo of young people whose lives were tragically cut short. Many parents had written in desperation to an international organisation as nothing was being done by the national justice system. ‘They took our children away’ is a common refrain.

In keeping with a Sri Lankan tradition of using art for activism Amnesty International decided to launch a poetry competition on the theme of disappearances to see if exploring this medium would provoke citizens to think anew. The competition ‘Silenced Shadows’ provided a creative space and an opportunity to share reflections and responses to this national tragedy. In English, Tamil and Sinhala, Sri Lankans from all communities and walks of life across the world were inspired to take part.[2].

Some of the entries explored the painful lack of closure:

Now I watch her

sit outside the skeleton of her house,

weaving palm baskets with dead fingers

and waiting,

still waiting

(An extract from ‘Still Waiting’ by Radhia Rameez)

Others touch on the impunity enjoyed by the perpetrators of this terrible crime:

Where is Raju, no one cares to answer.

At every detention centre, the same reply,

We know nothing about Raju,

Have not seen or heard him.

Where is the complaint,

The arrest warrant,

The interrogation record, the case file.

No answer to such questions.

(Extract from ‘Waiting for Raju’, by Basil Fernando)

This quest for the missing has become a tragic leitmotif of Sri Lanka no matter how keen official narratives are to sweep the issue of the disappeared into the shadows. Reading through some of the entries however I felt encouraged that contributors to ‘Silenced Shadows’ have created a cultural counter-memory to the erasure of the state. Counter-memories are important given the reality that the crime of disappearances has been used by the Sri Lankan state as a tool of terror when it has found itself unable to deal with dissent or revolt.

A common vice of states is to try to take control of history. We know this from the UK’s imposition of imperial narratives and also Latin America. It’s hard to imagine now that a song by the singer Sting ’They dance alone’ inspired by the mothers of the disappeared in Latin America was once banned by the government of Chile. Sting was fascinated by the dance mothers would perform to remember their children, the only form of protest they were allowed. In 1990 Sting participated in the Amnesty International’s Human Rights concert series across Latin America and was deeply moved when he performed on stage with mothers of the disappeared holding up photos of their loved ones.

Families in Sri Lanka are well practiced at bearing witness, challenging official memories, continuing to ask questions, giving testimony and sometimes taking to the streets. In January 2015 one woman broke through state disdain for free expression by smashing coconuts outside Temple Trees. The woman in question Sandya is the wife of disappeared journalist Prageeth Eknaligoda. She used a traditional form of cursing to expose the lack of inaction by the state. Travelling across Sri Lanka and even globally she maintains a steadfast campaign to try to find the truth about her husband. Sandya notes:

“There are so many commissions and legal bodies that previous [Sri Lankan] governments have set up but they have all failed to fulfil their responsibility to the victim’s families. That’s an example of how the domestic processes aren’t working properly.”

Speaking to her this week I sensed frustration over the lack of transparency about the proposed Office for Missing Persons and unease that victims were not properly involved. Despite the recommendations of the Lessons Learned and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC) to expedite investigations into the issue and despite the promises of the Paranagama Commission families still lack confidence. “Families are fed up of crying tears’ she notes, ‘we have to fight for our rights’. And just this week mothers have had to take to the streets again demanding proper investigations.

Some fans of the Frankfurt school might lament that ‘there can be no poetry after Auschwitz’ to borrow Adorno’s phrase. But the gift of art forms – be it poetry or drama is that it opens up new ways of seeing. When I was 13 my grandmother (who was living in Spain at the time) took me to the Prada a famous art museum in Madrid. The Prada is an imposing building with various illustrious exhibits. My grandmother didn’t want my sister and I to trudge through corridors feigning interest in gothic art or admiring endless marble statues. She wanted us to visit just one room and appreciate Las Mesninas a painting by the artist Velasquez. It is very powerful and certainly to a 13 year old’s mind an enigmatic work of art. Like Thenuwara’s ‘Camouflage series’ Velasquez wants us to critique what appears to be reality and look at what is in the shadows. In the painting the Royals appear to take pride of place but then the viewer notices others off stage and the intimations of a more complex social and political life at Court.

Art matters as it seeks to pose questions – it does not masquerade as something coherent. This is why it is interesting to explore different mediums and open ourselves to what they might tell us about issues. Amnesty International launched Silenced Shadows as a gesture of hope. Poetry is a form of bearing witness. The theme may be sombre and many individuals responded with anguish but there has also been much courage and solidarity remembering those missing.

In the aftermath of Pinochet’s violations in Chile Sting sang that the anguish of mothers was unsaid but he also knew one day they would sing their freedom. The contributors to Silenced Shadows are breaking the silence and starting new kinds of conversations. There is of course a rich history of Sri Lankan writers exploring themes of loss and suffering from Anne Ranasinghe to S Pathmanasam to Oddamavadi Arafath and many more. What I value about the Silenced Shadows entries is they suggest a new curiosity about personal and artistic freedom.

It’s a long time since I stood in the courtyard of the Heritage Gallery discussing art and critical theory. Since then contexts have changed and the city Colombo hurtles to embrace new buildings and ways of living. The way issues are raised and discussed has evolved. The silence has been cracked open by a variety of advocates and by people exploring issues through drama and song. There have even been a number of memorials built for the Disappeared and not without controversy. The state has acknowledged the trend of disappearances by establishing a number of Commissions. Through all these changes victims’ families have had to keep strong and constantly maintain their resolve for truth. What I have learnt is that Sri Lanka has a history of atrocity and trauma but also richness of culture and the resilience of those who love and will never forget their loved ones. To many disappearances are not just inconvenient truths but visceral facts that leave their pain on the body. WAN’s sari project is a testament to this.

The poems in Silenced Shadows showcase the violent personal and social histories of the nation. They provoke the reader to want something done, to act. Amnesty International aims to publish a multilingual book and launch this in Sri Lanka later in the year. But art alone is not enough. Let’s hope the moment has come for the Sri Lankan government to acknowledge the need not just for words of solace or another Commission but for action. And there’s actually something very straightforward that can be done. One of the main causes for the persistence of enforced disappearances across decades is undoubtedly the absence of laws that criminalize this practice. It’s time to pay tribute to those brave enough to bear witness by enacting legislation criminalising disappearances.

(Yolanda Foster has lived and worked in Sri Lanka. She is an alumni of SOAS, University of London. She now works with the South Asia team of Amnesty International.)

###

[1] “Disappearances” and political killings reached tragic proportions in Sri Lanka by the late 1980s, after several years of increasing numbers of people falling victim to these gross violations of human rights. In the northeastern part of the country, government forces confronting an armed Tamil separatist movement evolved tactics of “disappearance” and political killings to sow terror and avoid accountability. In the south, where the security forces sought to suppress an armed insurgency within the majority Sinhalese community, tens of thousands of people are believed to have been murdered under the cover of “disappearance” between 1987 and 1990. Sri Lanka: “Disappearance” and murder as techniques of counter-insurgency , Amnesty International, AI Index: ASA 37/13/93

[2] See, http://join.amnesty.org/ea-campaign/action.retrievestaticpage.do?ea_static_page_id=4326