Since 2009, Jaffna has become host to hordes of curious tourists, visiting to see what a city ravaged by war looks like. For the residents, there are many bitter memories. It is difficult to have a conversation where the war doesn’t crop up.

Some, though, are trying to move on with their lives. Slowly but surely, space to express grief and share memories is opening up – and the arts is playing a big role in this.

Founder of the Centre for Performing Arts (CPArts) Father Saveri is a respected figure in Jaffna. Having received a BA and MA in Theology in Rome, he also has double Doctorates in History and Hindu Philosophy.

To him, looking at the Fort brings back a terrifying memory.

In 1971, the Centre for Performing Arts staged a passion play set inside the Jaffna Fort, with 350 people participating.

The choice of location was deliberate – the Centre wanted people to draw parallels to the city of Jerusalem. However, they also chose to address some of the Fort’s bloody history during colonial times.

During the Dutch period, the Fort was used for public hangings, and the crucifixion scene was staged on the very spot that the hangings took place, in acknowledgement. In addition, bridges were built linking the outside of the fort to the centre, and these too were used as a stage. More than 100,000 people arrived to watch the play.

The show started at 7pm as scheduled, but the SP soon sent word that there was bad news, and the show should be ended promptly. While the actors were getting dressed, Fr. Saveri noticed a group of unknown people, but assumed that they were part of the lighting crew, who had come all the way from Colombo.

1971 was also the time of the first JVP insurrection.

The first bullets started flying as soon as the play ended.

We were caught up.… we didn’t know what was happening. Bullets were flying just over our heads,” Father Saveri recalled.

Thankfully, none of them were hurt in the ensuing chaos – although curfew was declared, and the lighting crew from Colombo ended up stranded in Jaffna for quite some time. In an unprecedented display of forgiveness, Fr. Saveri provided sanctuary to other JVP members who came knocking in the night, allowing them to sleep in the church. ‘They were lost, and needed a place to stay. Those who were caught were truly tortured,’ he recalls with genuine empathy.

Now over 50 years old, the Centre for Performing Arts tries to bridge divides through the arts – and has done so successfully, even during the height of the war. It has 20 centres across the island, featuring both Sinhalese and Tamil artists. During the war, the Centre was the first to transport a dance troupe from the South to the North by ship. They have staged demonstrations of Kandyan dance in Jaffna, and even had a Sinhalese art festival during the ceasefire, where dancers performed the maname. The Centre has also organized a children’s Parliament, comprising of 1000 children from all across the island. Fr. Saveri has also personally funded groups of Sinhalese, Tamil and Muslim students to visit Europe, no less than 14 times. Their partners include Prof Sarachchandra, creator of the play Sinhabahu, Kemalatha Subasinghe and Jerome de Silva.

All of these acts are for a single purpose – bridging racial and cultural divides. “This is a must for Sri Lanka, otherwise the country will be lost. Inter cultural living is the only solution to the problems we face in Sri Lanka,” Father Saveri said. It is a goal that the Centre has achieved fairly successfully, even during the height of war. With a wry smile, Saveri recounts the tale of a member of the Sinhala Urumaya who intended to spy on the Centre’s activities, but later had a complete change of heart. He now performs, alongside others, at the Centre.

Father Saveri isn’t the only person to emphasise on the importance of the arts as a tool for reconciliation.

Thamotharampillai Shanaathanan, senior lecturer of art history at the University of Jaffna believes the arts are ‘crucial’ as a stepping stone towards healing and reconciliation. He adds that while reconciliation has perhaps not been achieved in the way that the upper-middle-class has conceived of, there are, and continue to be, spaces for people to express themselves and the loss they faced in religious ceremony, rituals and art, including folk art. For instance, Shanaathanan recounts a tale of a performance of kolam dance in Mullaitivu, which was witnessed by some Sinhalese friends of his.

“It was a real lamentation. And the loss that was being narrated as part of a performance, became about the very real loss [these people had faced]. The Army couldn’t control it, because it’s part of the story,” Shanaathanan explained. In his classes, too, students will often deal very directly with their experiences of conflict. “As teachers, we try to teach them to express themselves in a different, less direct way… without killing their soul,” Shanaathanan said.

Jaffna, as a town, has had conflict built into bricks and mortar, even during colonial times. “The Dutch found Jaffna a darling city. They thought it was like their home,” Shanaathanan said. As a result, their influence can still be seen in the architecture of many Jaffna homes. However, the residents still held on to their unique identity, incorporating many features of Dutch architecture with locally available materials like palmyrah, to create something unique to Jaffna.

Unique, too, was Jaffna’s Thesavalamai law, which governed the lives of residents. Thevasalam gave daughters property rights (as opposed to laws which allowed for property to be inherited solely by first born sons). It also ensured that property be sold to neighbours as a first priority, rather than outsiders. Even the harvest of a fruit tree was provided for, should it grow in between neighbouring properties – with one third of the fruit left on the tree to ensure sustainability. The Dutch wisely did not interfere too much with the Thevasalam laws, but rather introduced their own where there were gaps.

So Jaffna town grew, with its own culture – but that was soon shattered by war.

And yet, to look at the town today, you would think it had never been touched by conflict, Shanaathanan points out.

The chance to memorialise spaces has often been glossed over (as in the case of the Jaffna library, which was totally renovated without public consultation) or else, done in a way that inspires unease among residents (as in the case of the war memorial in Kilinochchi).

In some cases, the value of memorialisation isn’t even recognised. The Jaffna Fort, for instance, is a symbol of oppression. Shanaathanan recounts a door-to-door campaign with the Heritage department, where he and his colleagues visited vendors, to convince them to stop selling parts of the damaged Fort to tourists from the South as ‘artefacts.’ “Well, the LTTE tore down these walls [during their occupation of the Fort] so why can’t we sell them?” an antique seller had asked.

For his part, Shanaathanan has tried to encourage and foster the preservation of memories – even if they are bitter ones. A collaborative 2004 project with S. Kannan, K. Tamilini, K.S. Kumutha, R. Vasanthini, called ‘History of Histories’ displayed material collected from 500 houses in the Jaffna peninsula, along with the owners’ memories of 20 years of life in Sri Lanka. This was displayed in the Jaffna library. In a subsequent project in 2011, ‘The Incomplete Thombu’ Shanaathan overlaid ground plans drawn by displaced people by memory with architectural drawings and renderings – bringing home the personal losses faced by many displaced people.

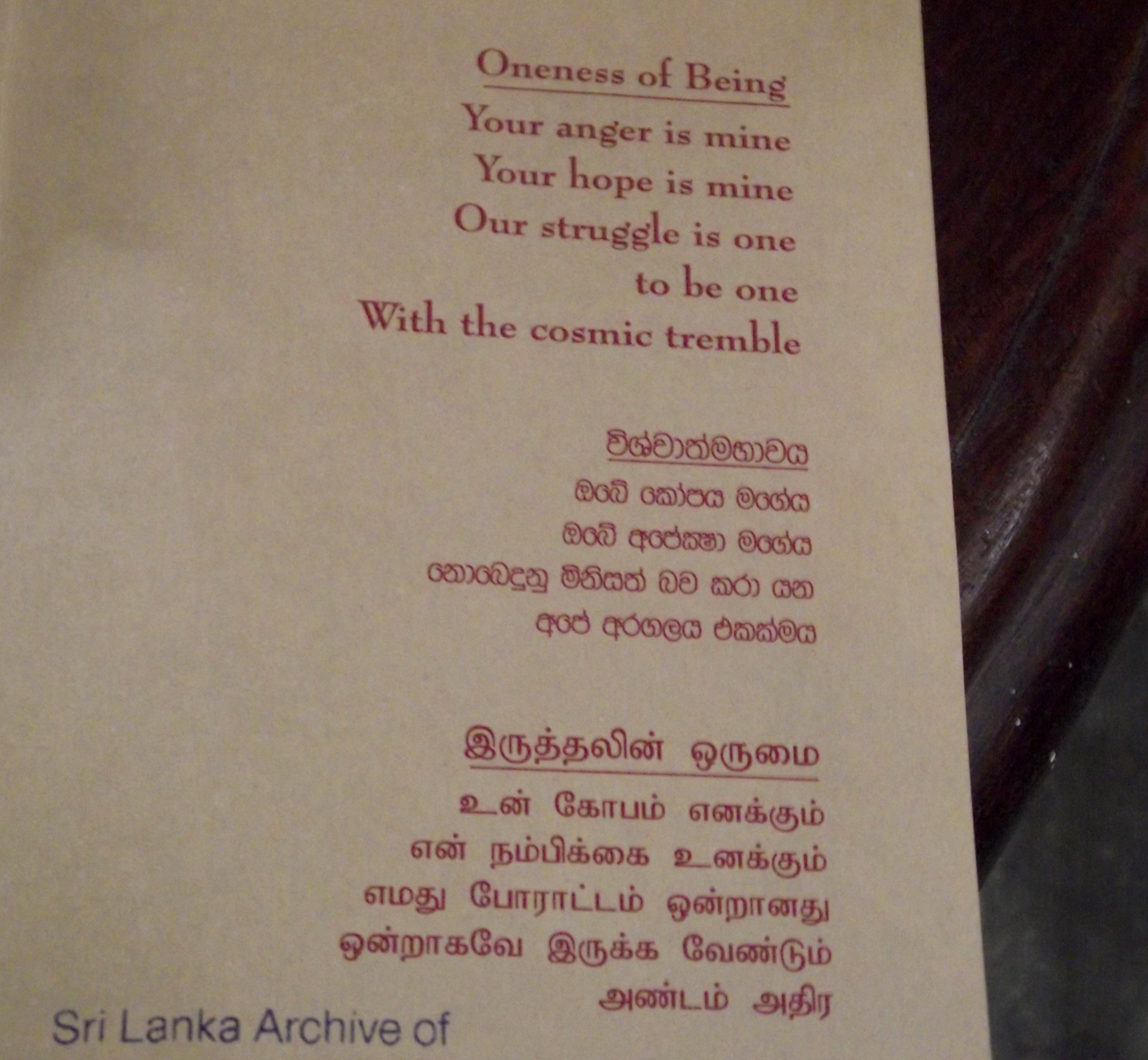

In addition, he’s also attempting to archive visual culture as a co-founder of the Sri Lanka Archive of Contemporary Art, Architecture and Design. Here, you will find shelves of texts, relating to these three fields, including pamphlets of art exhibitions held in Jaffna and featuring local artists.

The Archive is also a space for discussion, having hosted several guest lectures by artists, filmmakers, art historians, designers and architects.

Slowly, but surely, Jaffna is beginning to rebuild itself – but while the town boasts shiny new buildings and banks, healing the wounds of war takes time. Thankfully, people like Father Saveri and Shanaathanan, alongside countless others, are here to lend a helping hand.