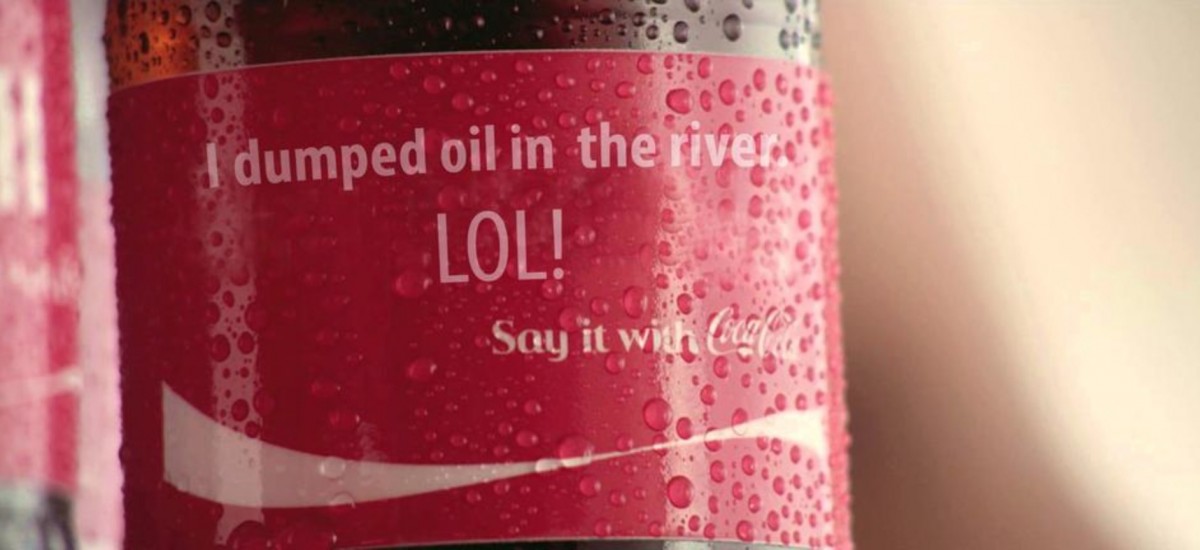

Photo courtesy @dumindaxsb

How Coke is undermining the media and Good Governance in Sri Lanka

Almost all major mainstream media outlets in Sri Lanka are now owned, or partially owned by individuals representing both business and political interests. This ownership simply treats media as a wing of a business conglomerate, and uses ‘objectivity’ merely as an essential product feature without which the market for their news would erode.

Strategies of media control, since the end of the war in 2009, have progressed far beyond the use of force and coercion to more sophisticated, invisible techniques. Noam Chomsky in ‘Manufacturing Consent’ names 5 ways in which big media exercises power, and is exercised upon by power interests. The interests of media ownership; the interests of key advertisers; control over sourcing of news (usually due to ability to mobilize reporters); flak or backlash from power lobbies; and bogeyman-ism (in the original context communism, and today Islamic terrorism, locally a bogeyman can be the LTTE, ‘foreign conspiracies’, take your pick) as a control mechanism. None of which Sri Lanka’s media industry is a stranger to.

The gravity of the current Coke fracas in Sri Lanka, the company’s latest mess up in a series of water contamination cases globally, goes beyond than the incident itself, the proportions of which are grave and serious enough. The apparent impunity which Coke is enjoying and the silence in public discussion around the issue rather, is a sign of an emerging new nexus of corruption in Sri Lanka. That of government, foreign multinationals and big media.

Coke has significant clout as a big advertising spender in the media sphere and is exercising its financial clout to either silence, reframe, or trivialize public discussion around the oil spill in the Kelani River and contamination of the water supply of hundreds of thousands of people. Coke is also global multinational which, in Sri Lanka, is backed by significant interests in local and international government; advantages it is showing no hesitation to use as influence to try and keep things quiet around the Kelani spill.

Sources from within two of Sri Lanka’s largest multi-lingual radio/TV/web news platforms told me that there were strict directives from higher-ups in the organization to not touch the Coke issue. If reporting must happen, it must happen in the most neutral, unassuming manner possible. A mere nod to the incident’s vague existence. A few months ago the directives to treat the MSG scandal of Nestle India were the same. Only a few brave outlets, most notably The Nation, have chosen to go ahead and lead with the story regardless of potential losses to ad revenue they might incur.

Coke is yet to issue a public statement, to come out and take ownership of the spill, and of the massive damage it has caused, the proportions of which we do not know because of delays in official government investigations and a dearth of independent media reportage. It has instead chosen to strategically reach out to a select few voices speaking out on the issue as and when they feel it is needed, tactically attempting to isolate its Public Relations. No doubt in the hope that the whole issue can be buried and covered up before it becomes a disaster that compounds the multinational’s global track record of environmental pollution and damage to human life.

Corruption, sometimes, is more sophisticated that a gossip site flashing pictures of Namal Rajapakse’s watch collection, or smooth talking politicians on TV talk shows presenting easy-to-digest damning statistics about just how much another politician took under the table. Sometimes the biggest acts of corruption happen with complex bond deals and financial market rigging, or in the shady commerce between what is news and what is truth readily manipulated by entities long practiced in the art of deception. But we seem to have difficulty in acknowledging a problem unless it is affirmed first to us by mainstream media; who are becoming adept at sensationalizing non-issues and underplaying important ones, or the problem has become so blatantly obvious that to not act would mean to doom ourselves to damnation; this is what finally unlocked mass public outrage against the actions of the BBS and the social-media led ousting of Rajapakse popularity.

If manipulation is the answer to the question of mainstream media silence, is complacency and distraction the only answer to why there is still no widespread call for Coke to be accountable in the Sri Lankan social media sphere? Or is there another, more sinister, more depressing reason? An online petition calling for accountability from the company has barely reached 2,000 signatures and initial activism based around hastags like #cokePollutes and #NoCokeSL have received lackluster purchase from a large sector key influencers online, and again, free use of its money might be the answer.

Coke has been very active in sponsoring various ‘real-life’ events in the social media sphere, money that has been gladly and unquestioningly accepted by the country’s (read Colombo’s) vibrant, active and influential small community of online intelligentsia which has continuously partnered with corporate interests. Has sponsorship money and the promise of more sponsorship money bought the voluntary silence of the country’s urban, usually easily outraged Twitterati and Facebook armchair activists? Consent, it appears, is apparently being manufactured not just in mainstream media, but also online.

The Coke oil spill, the apparent impunity and lack of concern of the company, the near-complete silence of mainstream media, and the lack of government zeal in pursuing a public interest angle to the whole crisis is indicative of the beginnings of a new paradigm of corruption. We need to wake up and smell the coffee, which now smells like diesel. Will we, the population that used our voices to such great affect, go back to simply not caring until the proverbial matter hits the fan, compounding the problem in the process? Or will we try to critically look beyond the issue and see not just a major threat to our health through an incident of water contamination; to be dealt with and fought against and thereafter forgotten, but an even bigger threat to the new era of politics we helped usher in?