Introduction

When I went to Trincomalee last November with a few university friends I noticed a distinct unfriendliness in the air. While growing up, I often visited Trincomalee, because my cousins lived there. Now the Trincomalee I knew and loved from my childhood was no more. Something else had taken its place.

Trincomalee today is a place where the collective existence of minorities are increasingly under threat. What follows is my attempt at unpacking the key trends of the Government’s ongoing political project of transforming Trincomalee into a Sinhalese-Buddhist town. An analysis of the new Trincomalee captures the very essence of the general trajectory of Sri Lanka’s post-war journey.

An Exploration: Makings of the New Trincomalee

1. Rewriting of History and Rebranding of Trincomalee as a Sinhalese Buddhist Town

The government held Sri Lanka’s 65th Independence anniversary celebrations in Trincomalee last year. The occasion could have fostered inter-ethnic harmony and peace. However, President Mahinda Rajapaksa’s speech on the 4th of February painted a strictly anti-pluralist and pro-Sinhalese nationalist vision for Trincomalee. His reading of Trincomalee’s history, too, was exclusively Sinhalese-Buddhist, despite there being ample evidence of the town’s rich multicultural past.

The President followed up his account of the town’s ancient history with some highly provocative comments about Trincomalee’s immediate past. Completely ignoring the political background and unlawfulness of the controversial Buddhist statue erected in 2005, he stated that “there was no peace or freedom even for the sacred statue”[1] during war days. That the statue was placed in the middle of Trincomalee town overnight, under the cover of darkness (with the backing of the Navy and JHU), amidst rising ethno-religious tensions in the area escaped mention[2].

Further, he did not say a word about the ancient Koneswaram Temple, or about Trincomalee’s significant place in secular history as an emporium and meeting place for many cultures and religions.

This prompted political columnist Tisaranee Gunasekara to note that “the President’s decision to ignore the pluralist and secular histories of Trincomalee and to give that multi-ethnic/religious city an exclusively Sinhala-Buddhist past was not an accident”, but rather “a coded-acceptance of the JHU/BBS vision of a Sinhala-supremacist Sri Lanka.”[3]

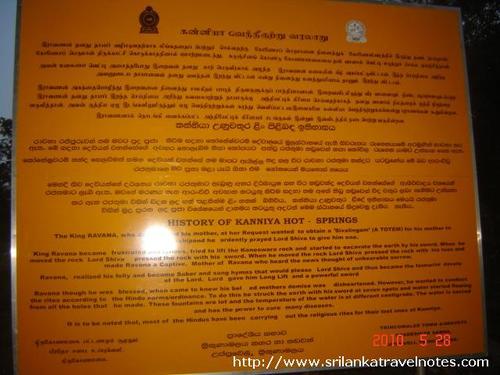

Strong evidence from the ground backs up Tisaranee Gunasekara’s claim. For example, until at least 2010 the official history of Kanniya Hot Springs connected them to the Ravana legend[4]. But now the Archaeological Department—which has taken over the springs[5]—has reversed this. The revised account, available on a signboard only in Sinhalese and English, claims that the wells were part of a Buddhist Monastery.

Figure 1: The Old Information Board

While I do not intend to contest the historical claim of the new information board, it does prompt several urgent questions. What purpose does the government hope to serve by not including up a Tamil translation? If the ‘new’ historical claim is indeed true, would it not make sense to let the Tamil population know? And what archeological evidence prompted the alteration?

In addition to this, a Buddhist temple has cropped up in the vicinity. Kanniya Sivan Kovil – located close the wells, inside the premises – once a major local attraction, has now been deliberately made an insignificant place. Armed violence partially damaged the Sivan Kovil in the 90s. Despite this, the Kovil continued to be a vibrant place and regular poojas were held. Today, nothing remains of the old temple structure. My attempts to get to the bottom of what exactly happened have proved futile[6]. However, the statues of the temple have been placed inside a dusty room. I found all kinds of objects inside the worship place – including a few mud-covered spades and a bicycle; Hindu friends who accompanied me were visibly upset by what they saw[7]. When the newly constructed Vihara is contrasted against the plight of the Sivan Kovil, the picture is telling.

As for Koneswaram Temple, a historically significant Tamil monument, I could not find a single Tamil vendor in the shops near it. Before its destruction by the Portuguese, the original temple represented a splendid piece of Pallava architecture, after the same pattern as the rock temples of Mamallapuram. Pallava influence also emerged in the form of Mahayana Buddhist monuments along and interior to the east coast. This plural heritage is being systematically destroyed.

Nothing relevant to the Koneswaram Temple was on display in the stalls – owned by Sinhalese traders – that decorate either side of the road that leads to the temple. However, Buddha statues and post cards carrying pictures of Viharas were available in abundance. Sinhalese vendors appeared in the temple premises sometime after the erection of the Buddha statue, and their arrival at the scene was one of the many politically driven steps that heightened ethnic tensions in Trincomalee[8]. I remember a time when the path leading to the temple cut through lush greenery. Tame spotted deer casually strolled along with visitors back then. Today, this unique pleasure has been replaced with the sight of garbage and plastic bags, thanks to the long line of shops. In addition to these Sinhalese vendors, the Navy runs a large canteen. Close to the canteen is a single-barrel artillery piece, seemingly waiting to shoot down a non-existent enemy vessel. The presence of the Navy and the stalls of the Sinhalese vendors give the place a distinctly non-Tamil flavor. Until visitors reach the summit of the rock upon which the temple sits, they do not feel as though they are journeying towards a Hindu temple that boasts more than 2500 years of history[9].

Figure 2: Long line of Shops owned by Sinhalese

And finally, a portion of land opposite Trincomalee’s Nelson Theatre was recently fenced off and declared sacred. Whether a Buddha statue may soon (?) sit beneath the Bo Tree on that land, no one knows.

The President’s Independence Day speech and the corroborating ground evidence reflect what truly is happening in Trincomalee. Trincomalee, a town that boasts of a rich multicultural heritage, is being transformed into an exclusively Sinhalese-Buddhist town. His blatant denial of a place for minorities in Trincomalee’s past indicates the place his government plans to assign for Tamils and Muslims in Sri Lanka’s future.

2. Politics of Land and Livelihood: Alteration of Demography and Economic Marginalization

Land is, in many ways, at the heart of the ethnic conflict. State-sponsored land distribution schemes were an important cause of the explosion of ethnic violence in the 1970s and 80s. Moreover, access to land is critical to many things, both at the family and community levels. When access to land is denied in a postwar context it results in continuing displacement of families and restrictions on livelihood activities. Further, at the community level, it hampers the local economy and disempowers communities.

In Trincomalee, access to land has become a grave problem for minorities. Private lands belonging to Tamil and Muslim families have been taken over by the military and the government, in the name of High Security Zones and Special Economic Zones. The legality of such takeovers remains unresolved.

The name of one such affected village, Sampur, derives from the Tamil word ‘sampooranam’, meaning ‘richness or abundance’. The village is blessed with natural resources. Prior to 2006, despite the constant menace of the war, Sampur had a self-sufficient economy. According to the Government Census of 2008[10], 1940 families lived in Sampur, comprising 7,494 individuals. The people of Sampur led fulfilling lives, and were good-natured folk. The bond that they shared with their ancestral soil was fundamental to their happiness.

In 2006, the entire village was displaced. Initially, the families were scattered across Batticaloa district. In 2007, under government pressure and with the promise that they would soon be resettled on their own land, people returned to Trincomalee district. Seven years have passed since, but the people of Sampur continue to languish in IDP camps. Their persistent calls to return to their lands of origin have been ignored. As a community they have steadfastly refused relocation. The Board of Investment has taken over up to 1700 acres of Sampur’s fertile land for 100 years on lease, and declared it a Special Economic Zone. The proposed relocation spot, Soodakuda, is far less fertile, with hardly any access to water[11]. The people of Sampur, who are traditionally farmers and fishermen, stand no chance of continuing their preferred and traditional livelihoods in Soodakuda. Offering twenty perches of infertile land as compensation for acres of richly fertile soil cannot be justified. Further, the conditions in the IDP camps are extremely harmful to both the mental and physical health of their occupants. The social fabric of the community has been torn apart, with underage sex and related social problems rampant.

In Kuchaveli DS Division, paddy cultivation lands belonging to Tamils have been taken over by Sinhalese with political and police backing. Ownership claims submitted to the DS are neglected and authorities have taken no action to stop this criminal activity. In a report published in 2010 on land-related issues in the East, referring to Irakkandy, a village in Kuchaveli DS Division, CPA notes:

“CPA was also informed that the Sinhalese were encouraged to return and have been provided assistance by politicians in the Central Government and the GA who is also Sinhalese. The Sinhalese are also provided protection by the Navy and the Police.”[12]

High Security Zones continue to be a hindrance to around sixty fishermen in Sampur, as their traditional waters continue remain inaccessible. In 2011, the President opened up a new fish market in Trincomalee town. All the slots are occupied by Sinhalese traders.

Figure 3: Recently Opened Fish Market in Trincomalee Town

3. Military and the Role of the Arms of the State in Alienating Minorities

Tamil residents in Trincomalee town still shudder when recounting stories from 2011’s Grease Yakka days. While the perpetrators got away scot-free, the police arrested those who complained or screamed upon being attacked. A recently married couple told me that they were mortally afraid during that time. While there were reports of Grease Yakka sightings in Sinhalese settlements, such sightings were few and far between; the affected communities were primarily Tamil. Importantly, Sinhalese also had the (mental) space and freedom to set up sentry points – with men carrying large knives – in their areas. Tamils, on the other hand, could hardly raise their voices in fear.

Trincomalee’s GA is a retired military man, who repeatedly and publicly declares that ‘Sri Lanka is a Sinhalese Buddhist country’. At public gatherings, he speaks to largely Tamil audiences in Sinhalese; Trincomalee residents complain that the man does not even have the courtesy to appoint a translator. His decisions are rarely just, especially in matters concerning sensitive issues such as land and resource distribution[13]. The Divisional Secretaries are a helpless bunch without any independent decision-making power. The overwhelming view of the Trincomalee townfolk I spoke to is that Mrs. Sasidevi Jalatheepan, the Divisional Secretary of Trincomalee town, consistently prioritizes Sinhalese concerns over those of minorities.

The military’s involvement in civil affairs is increasingly worrying. It plays an active role in preventing, disturbing and discouraging civil mobilisation. In villages, especially where people have been resettled, the military monitors public meetings and questions visitors. Despite the passing of five years since the war ended, the military continues to block access to IDP camps for INGO, NGO workers, and activists. An INGO worker confided that it is customary for military personnel to follow their vehicles and try to extract as much information from their drivers about them during field visits. The tone of such questioning is often intimidating.

Conclusion: Lessons from Trincomalee and its Implications for the Future

The experience of minorities in the beautiful eastern district of Trincomalee perfectly encapsulates the dark and depressing reality facing minority communities across Sri Lanka. Trincomalee’s remaking is part of a larger national-level project. The new Trincomalee is a microcosm of the post-war Sri Lanka. At the expense of minorities, the Rajapaksa government is building a Sinhalese-Buddhist nation that is intolerant, illiberal, and regressive.

Five years on, any possibility of national reconciliation seems entirely distant and improbable. In retrospect, it is evident that the war never ended. Only armed fighting did. The government has only exacerbated the root causes that led to the original conflict. The future looks bleak indeed.

###

[1]President Mahinda Rajapaksa, 65th Anniversary Address, 2013 – http://www.president.gov.lk/speech_New.php?Id=129

[2] For a detailed report: Nanda Wicremasinghe, Erection of Buddha statue produces communal tensions in Sri Lanka, World Socialist Web Site – https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2005/06/sril-j09.html

[3]Tisaranee Gunasekara, President Rajapaksa – http://dbsjeyaraj.com/dbsj/archives/16037

[4] See the attached picture.

[5] The dynamics of this takeover is a bit ambiguous. Military continues to play an active role, performing various duties including selling of tickets and maintenance of the premises.

[6] A piece on defense.lk claims that a portion of the kovil’s wall was demolished by the Archeological Department to avoid any inconvenience to visitors: http://www.defence.lk/new.asp?fname=20111209_05

[7] As noted in footnote 4, Military is in charge of maintenance of the site. Thus, they are responsible for the state of the worship place.

[8] Trincomalee Tamils experienced a particularly difficult period in 2005-2006. The massacre of five Tamil students by the Navy in 2006 left a permanent scar.

[9] The temple is mentioned in both Mahabharatha and Ramayana (400 – 100 BCE). Konesar Kalvettu, the 17th Century stone inscription of the temple, gives the date of birth of the shrine as circa 1580 BCE. Koneswaram Temple’s official website notes that the temple has a history that stretches 3287 years.

[10] NAFSO, Sampoor: Facts vs. hype on Sri Lanka’s ‘post war recovery’, Journalists for Democracy Sri Lanka – v http://www.jdslanka.org/index.php/2012-01-30-09-31-17/human-rights/171-sampoor-facts-vs-hype-on-sri-lankas-post-war-recovery

[11] According to informed sources, the government is in the process of finding other suitable relocation spots.

[12] Bhavani Fonseka and Mirak Raheem, Land in the Eastern Province: Politics, Policy and Conflict, Centre for Policy Alternatives

[13] For example, he supported illegal Sinhalese settlers in Irakkandy in Kuchaveli DS Division. (See footnote 12)

###

This article is part of a larger collection of articles and content commemorating five years after the end of war in Sri Lanka. An introduction to this special edition by the Editor of Groundviews can be read here. This, and all other articles in the special edition, is published under a Creative Commons license that allows for republication with attribution.