This is a summary of a longer report. Please download it as a PDF here or read it online here. All photos taken and provided by the author.

Introduction

According to Article 7, paragraph 2(i) of the Rome Statute[1], an Enforced disappearance is defined as “…the arrest, detention or abduction of persons by, or with the authorization, support or acquiescence of, a State or a political organization, followed by a refusal to acknowledge that deprivation of freedom or to give information on the fate or whereabouts of those persons, with the intention of removing them from the protection of the law for a prolonged period of time”.

Often when addressing the issue of enforced disappearances, the focus is on either the disappeared person, or the perpetrator. Rarely is the focus on the families that are left behind to cope with their grief and pursue justice for their disappeared family members and themselves. In a country like Sri Lanka, where no official structures are in place to provide recourse and render comfort to the families of the disappeared, the extent of their vulnerability is largely dependent on their awareness of their rights, their access to justice and available support systems.

The objective of this Watchdog report is facilitate the criminalization of enforced disappearances in Sri Lanka, recognize and uphold the rights of the families of those who have disappeared and repeal the draconian Prevention of Terrorism Act No 48 of 1979, under the auspices of which the State and its organs carry out enforced disappearances.

Recent incidents

The 70s, 80s and 90s saw enforced disappearances in Sri Lanka at their peak. This coincided with the two JVP- led insurrections and the armed ethnic conflict which commenced in 1977. While enforced disappearances were sporadic during the early 2000s, with the election of Mahinda Rajapakse as President in 2005 and the onset of Eelam War IV in 2006, they became widespread and systematic once more. Since then enforced disappearances have occurred island-wide, but more so in the highly militarized North and Eastern Provinces and the capital, Colombo, targeting dissenting voices and the Tamil community.

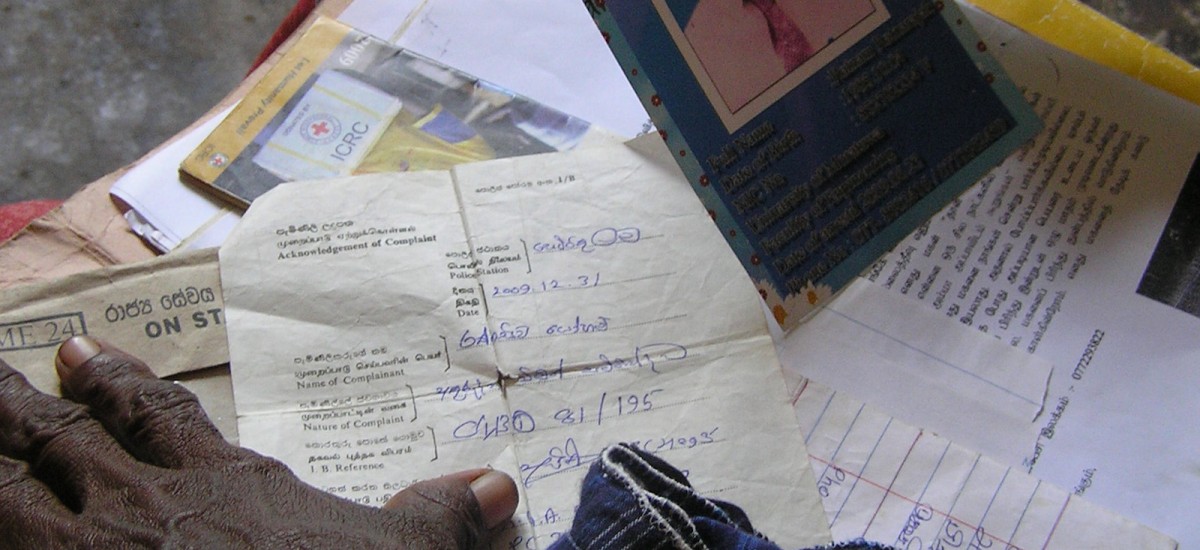

A. Jeevaraja, a first year Advanced Level student was forcefully conscripted by the LTTE in the months preceding the conclusion of armed hostilities. On 24th March 2009, Jeevaraja, who had sought refuge at the Valaignarmadam Church along with several others, had been forcefully taken away by the LTTE. His family had last seen Jeevaraja on 19th April while they were being displaced to Mullivaikkal. His father claims that he had heard reports from friends and neighbours that Jeevaraja had escaped from the LTTE and had been seen crossing over to Government territory just before the conclusion of the war. M. Balakrishnan, a father of two, was last seen on 18th May 2009 while surrendering at the Sri Lanka Army checkpoint in Omanthai, Vavuniya. Rajakumari, Balakrishnan’s wife, initially a resident of the Menik Farm IDP camp had handed over a letter to the Commander- in- charge of her zone at Menik Farm regarding her missing husband. She had also formally lodged complaints about her husband’s disappearance at the ICRC, the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) and the Criminal Investigation Department (CID). In the four years since her husband’s disappearance Rajakumari has also visited the Boosa detention camp and the CID headquarters in Colombo. She is yet to hear of her husband’s whereabouts. In June 2009, Ratnam Ratnarajah, one of six siblings and a second year engineering student at the University of Moratuwa, originally from Kilinochchi, disappeared in Vavuniya while on his way back to University.

In June 2013, 15- year old Sivasooriyakumar Sanaraj of Vavuniya did not return home after school. Nearly 6 months after his disappearance the police are yet to make any progress, even while two suspects have been identified in relation to his abduction. In September, Karthigesu Niruban, a teacher, originally from Kopay (Jaffna), was abducted in the vicinity of the Vavuniya Central Bus Station and has not been heard from since. In November 2013, a father of one from the Vanni was abducted in a white van by 6 men, blindfolded, detained at two separate locations for 10 days and then dropped off in a suburb of Colombo.

Also, in parallel developments, families of the disappeared from the North were blocked from attending non-violent demonstrations in Colombo by State security forces on two occasions in 2013[2][3] (the latter demonstration was part of the Human Rights Festival organized by civil society actors in the South, to coincide with the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting). Earlier in the year, during the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Navanethem Pillay’s visit to Sri Lanka, following her speech commemorating International Day of the Disappeared in Colombo on August 30, families of the disappeared from the North and East were intimidated and temporarily blocked from exiting the premises by Pro-Government protesters. Also during Pillay’s visit, this time to the North, on August 27, families of the disappeared protesting outside the Jaffna Public Library, where she was meeting with Government officials, were denied a meeting with her, as she was sneaked out of the back entrance of the Library by State security personnel.[4] Similarly, on November 15, 2013, families of the disappeared who protested in Jaffna in the hope of meeting visiting British Prime Minister, David Cameron, too were violently blocked from meeting him. Mothers and clergy were severely manhandled by the Police[5]. Further, a local human rights activist from Mannar, Sunesh Soosai, actively involved in championing the cause of disappearances in the North, and his family, was threatened by unidentified persons (suspected to be State intelligence officers), when they visited his home and made a threatening phone call to him on November 21[6] 2013. On 10th December 2013, the Committee for the Investigation of Disappearances organized a protest in Trincomalee to mark World Human Rights Day. Around 100 family members of those who had disappeared, activists and Provincial Council Members of the Tamil National Alliance (TNA) had gathered at the Trincomalee Bus Station. The protest was then attacked by around 30 masked men who tore placards and assaulted those who had gathered. The convener of the Committee for the Investigation of Disappearances, Sundaram Mahendran, was injured during the assault and was admitted to hospital[7][8][9].

This particular report aims to highlight and reinforce the rights of the families of those who have disappeared. It will also attempt to highlight the severe restrictions imposed in exercising these rights by in Sri Lanka by the State.

Article 24 of the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances (ICPPED) provides a broad definition of the term ‘victim’, which incorporates not only the disappeared person, but also all others made to suffer as a result of an enforced disappearance. The families are made to suffer due to the mental torture caused by the stress and anguish of not knowing the whereabouts and welfare of their loved ones indefinitely. Therefore, even though Sri Lanka is not party to the ICPPED, having ratified both the International Convention Against Torture (ICAT)[10] and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)[11], the State is obligated to ensure the mental and physical wellbeing of its citizens. Sri Lanka’s obligations to its citizens under the ICCPR and CAT provide avenues through which the mental harm caused to the families of the disappeared can be addressed.

Rights of the families

The Right to Know

Article 17.1 of the United Nations Declaration on the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance provides, “Acts constituting enforced disappearance shall be considered a continuing offence as long as perpetrators continue to conceal the fate and whereabouts of persons who have disappeared.”

The International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances (ICPPED) explicitly states that families are entitled to knowledge pertaining to “progress and results of the investigation and the fate of the disappeared person.”[12]

The next of kin of the disappeared are not only affected by the disappearance itself, but also by the continuous refusal by the State and its agencies to acknowledge or substantially assist in locating and/or providing information regarding the disappeared individual.

Further, individuals who pursue the truth face intimidation at the hands of the perpetrators (usually members of State security organs or groups aligned to them) by way of constant interrogation, threatening phone calls, being followed by unmarked vehicles or near constant surveillance. This is in direct violation of the State’s obligations as set out in Principle 10 of the Updated set of Principles for the Protection and Promotion of Human Rights through Action to Combat Impunity (“Effective measures shall be taken to ensure the security, physical and psychological well-being and where requested, the privacy of victims and witnesses who provide information to the commission.”[13]).

Families are forced to abandon their pursuit of justice in fear of reprisal by the State. This is a travesty of justice as families are not only forced to suffer their immense grief and trauma in silence, but are also deliberately denied the right to seek justice and redress for the wrong done to them.

The appointment of a Presidential Commission of Inquiry in August 2013, in line with the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC) recommendations, should be viewed against the backdrop of continued intervention by the State to deny access to information to the families about those who disappeared. It is feared that this Commission too would fail in its lofty goal of providing the families or next of kin with complete details about those who disappeared.

The Right to Justice

The right to justice is defined as a victim’s right to a fair trial, where the alleged oppressor is tried in a court of law and reparations are granted.[14] L. Joinet, in his groundbreaking report states that there can be no “lasting reconciliation[15]” without justice, and if forgiveness is to be granted by the victim, the perpetrator must first be made known to the victim, and forgiveness sought thereafter. The State is obligated to investigate violations and prosecute perpetrators, and if found guilty, punish them; failing which, the victim has the right to “institute (legal) proceedings themselves.”[16]

In Sri Lanka, institutional shortcomings of the judiciary also contribute towards the lack of justice for the disappeared. The lethargic and lackadaisical attitude of the judiciary is one of its most significant failings when giving effect to habeas corpus applications. Further, delays in the hearings and deliberation of habeas corpus applications, frequent postponements of cases and transfer applications made by respondent’s lawyers are other significant failings of the domestic judicial system.

Habeas corpus applications on behalf of disappeared persons are used in Sri Lanka primarily to exhaust all other possible domestic remedies. It is only after the habeas corpus application is filed that an international remedial is explored.

The presence of a comprehensive database comprising details and statistics of those made to disappear by successive Governments, Tamil militant groups, paramilitary groups associated with the security forces, extortionists and human traffickers is vital for the families to commence their quest for justice.

In a majority of cases of the disappeared in Sri Lanka, the perpetrators are individuals and/or groups linked to the State and it is quite clear that a largely compromised and ineffective judiciary is making very little headway in bringing them to justice.

Individuals named as perpetrators by the Commissions of Inquiry (CoI) in the past were never called to speak before any of the Commissions.

The Government of Sri Lanka with the entire State machinery at its disposal has demonstrated, through its inaction, the total lack of will to bring justice to the families of those who disappeared.

The Right to Reparation

Reparation to the families or next of kin of those who disappeared entails both individual and collective measures.

Reparation to these families is primarily assessed by monetary compensation and many governments resort to paying compensation since this would conveniently absolve it of the crime. ”[17] What these governments do not comprehend is that “behaving as if this monetary recompense has absolved them (the State) of any further responsibility, (it) further strengthens people’s perception of them as perpetrators.”[18]

In Sri Lanka, however, compensation is only awarded to victims who have been issued with a Death certificate (DC).

If the families of those who disappeared choose follow this process it would also translate as them having accepted the death of their loved ones. This would take the onus off the Government to be answerable and accountable to these families. The admission that the disappeared individual is dead is the only means to receive compensation and it is an unjust manipulation by the State[19]

The Association of Parents of Servicemen Missing in Action (PSMIA) in Sri Lanka has brought continuous pressure on the Government to specifically read as ‘missing’ rather than ‘killed’, when issuing death certificates to persons missing in action (MIA). Further, the LLRC rightly recommends that compensation cannot be considered in isolation and that it must be looked at in relation to the “overall resettlement and development strategy”[20].It is noted that “if there is no healing of memories, merely a repression, the untreated collective trauma could well turn into resentment and rekindle cycles of violence once again.”[21]

The Government in power and the State apparatus must realize that it is only by addressing the community’s grievances and ensuring that justice is served, is true reconciliation achieved and the natural course of healing take place. The Government should also facilitate symbolic measures intended to provide moral reparation.

On October 27th of every year, families of the disappeared, clergy and activists- commemoration The Monument for the Disappeared at the Seeduwa – Raddoluwa junction. There are no similar initiatives carried out by the State on behalf of victims or their families.

Guarantees of Non-Recurrence

A guarantee of non- recurrence could be provided by the complete disarmament of paramilitary groups linked to the security forces, the repeal of emergency laws (i.e. PTA) and the removal from office of senior officials implicated in grave human rights violations in the past.

The lack of will by the successive governments to carry out an island-wide disarmament programme is mainly because paramilitary groups linked to the security forces carry out a vast majority of their ‘dirty work’. As former US Ambassador to Sri Lanka, Robert O. Blake Jr. rightly observed, “Paramilitaries such as the…Karuna group and…EPDP have helped the Government of Sri Lanka (GSL) to fight the LTTE… by kidnapping and sometimes killing those ‘suspected’ (emphasis added) of working with the LTTE, thereby, giving the GSL a measure of deniability.[22] In many instances, the Government has continued to keep leaders of paramilitary groups in power and in cases, even promoted them with ministerial portfolios.

In almost all instances members of these groups and individuals linked to the perpetrators intimidate victims’ family members and pressure them into withdrawing applications from the High Court or into not pursuing justice.

An independent body comprising a panel of experts and professionals should be formed to devise a centralized system of data collection at the national level, integrating all information with regard to missing persons currently being maintained by different agencies.”[23]

Conclusion

Sri Lanka rates quite poorly in relation to international standards, norms and principles governing enforced disappearance. An independent international Commission must be set up to accept and evaluate submissions made by families, and ensure that due process is followed and justice is served.

There should be a comprehensive assessment of psychological and economic impacts caused to these families and the State should be obligated to provide for their mental and social welfare. Families of the disappeared should be provided psychosocial assistance and trauma counselling from specialists, and allowed to form networks with other families and support organizations.

The families and their support networks should also be provided the backing of established religious institutions. A multi- religious body comprising clergy and community leaders from all major religious denominations should lead the initiative to highlight the plight of the disappeared and their families.

Enforced disappearances should be eradicated from being used as a political weapon by the State. The State must also wholeheartedly commit to using exclusively legal methods to combat illegal activity.

Recommendations

- Stop with immediate effect, continued abductions and disappearances[24]

- Stop with immediate effect, all threats, restrictions and harassment of families of disappeared persons, and those who support them in their search for truth and justice

- Initiate investigations by the Police and the NHRC into all incidents related to above, including, but not limited to those incidents mentioned in the Right to Know, Right to Justice and Case Study sections of this report

- Publish in all three languages and disseminate through media, reports of all Presidential Commissions of Inquiry that have looked into disappearances, plus Committees and any such bodies.

- Publish a report regarding the status of implementation of all recommendations of above reports, by 28th Feb 2014

- Make a plan of action to implement all remaining recommendations by all previous Commissions of Inquiries and the UN Working Group on Enforced & Involuntary Disappearances, by 31st March 2014 and ensure actual implementation – in consultation with families of disappeared persons, lawyers, human rights activists, opposition politicians etc. Also establish an independent monitoring body comprising HRDs, civil society actors, lawyers and opposition politicians

- Criminalize enforced disappearance in Sri Lanka, in consultation with families of disappeared persons, lawyers, human rights activists, opposition politicians etc.

- Repeal the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA)

- Ratify the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (ICCPED) and the Optional Protocol of the Convention Against Torture

- Invite the UN Working Group on Enforced and Involuntary Disappearances to visit Sri Lanka by June 2014

- For the NHRC to establish a special mechanism / Unit to expedite all pending cases of disappearances, and publish a status report as soon as possible, including segregated data

- To fast track all pending and future cases of Habeas Corpus, and guidelines issued in this regard

- To put in place an equitable scheme of reparations for all family members of the disappeared, irrespective of their background, occupation, status, time period of incident, location of residence and incident, ethnicity, religion etc.

- To ensure that the issuance of death certificates is only at the explicit informed request of families of disappeared person, and that no person should be forced or coerced to accept death certificates

- To ensure that families of disappeared persons applying for death certificates, reparations etc. are able to state to the best of their knowledge, the circumstances, alleged perpetrators and background of the victim, without any coercion or condition

- To ensure that there are no legal and practical impediments for those families of disappeared persons to pursue truth and justice through campaigns and legal means, even after application for death certificates and reparations

- To expand or revise the mandate of the present Commission on Disappearances, in consultation with families of disappeared persons, human rights activists, lawyers and opposition politicians, to ensure that it becomes an independent and credible mechanism with a strong international involvement

[1] Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. http://www.icc-cpi.int/nr/rdonlyres/ea9aeff7-5752-4f84-be94-0a655eb30e16/0/rome_statute_english.pdf

[2] WATCHDOG, Police detains families of disappeared from Northern Sri Lanka and prevents peaceful protest and petition to the UN, Groundviews.org – http://groundviews.org/2013/03/07/police-detains-families-of-disappeared-from-northern-sri-lanka-and-prevents-peaceful-protest-and-petition-to-the-un/ & Marisa de Silva, Police impeding the movement of Tamils, Groundviews.org – http://groundviews.org/2013/03/06/police-impeding-the-movement-of-tamils/

[3] Sri Lanka Campaign – Police block demonstrators going south, while Government mob block journalists going north – http://blog.srilankacampaign.org/2013/11/police-block-demonstrators-going-south.html

[4] TamilNet, Navi Pillay taken through backdoor to avoid public in Jaffna – http://www.tamilnet.com/art.html?catid=13&artid=36594

[5] Ruki, British Prime Minister and TNA leaders shun families of disappeared in Jaffna, Groundviews.org – http://groundviews.org/2013/11/16/british-prime-minister-and-tna-leaders-shun-families-of-disappeared-in-jaffna/ & @gajenmahen, TwitLonger – http://www.twitlonger.com/show/n_1rrmt3u

[6] Sri Lanka Campaign, Reprisals start in Mannar – http://blog.srilankacampaign.org/2013/11/reprisals-start-in-mannar.html & Radarnews, Mannar Bishop requested to stop the atrocity of military investigators – http://www.radarnews.com/mannar-bishop-requested-to-stop-the-atrocity-of-military-investigators/

[7] BBC. Sri Lanka rally to protest against disappearances. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-25323892

[8] Colombo Telegraph. Families of Disappeared Attacked in Eastern Sri Lanka on Human Rights Day. https://www.colombotelegraph.com/index.php/families-of-disappeared-attack-in-eastern-sri-lanka-on-human-rights-day/

[9] Ceylon Today. Special Police Team to probe Trinco clash. http://www.ceylontoday.lk/16-49875-news-detail-special-police-team-to-probe-trinco-clash.html

[10] UN General Assembly, International Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, 10 December 1984, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1465, p. 85, available at: http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/3ae6b3a94.html

[11] UN General Assembly, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 16 December 1966, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 999, p. 171, available at: http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/3ae6b3aa0.html

[12] Article 24.2, UN General Assembly, International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance…Ibid.

[13] Principle 10, UN Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights, Updated Set of principles for the protection and promotion of human rights through action to combat impunity, 8 February 2005, E/CN.4/2005/102/Add.1, available at: http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G05/109/00/PDF/G0510900.pdf?OpenElement

[14] UN Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights, Question of the Impunity of Perpetrators of Human Rights Violations (civil and political), 26 June 1997, E/CN.4/Sub.2/1997/20, available here. (revised version)

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] T. van Boven, Reparations: a requirement of justice, El sistema interamericano de protección de derechos humanos en el umbral del siglo XXI. Memoria del Seminario, Tomo I, second edition. Inter-American Court of Human Rights, San José, Costa Rica, (2003), pp.654.

[18] G. Samarasinghe, ‘Coping with emotions towards perpetrators of violence: An essay on two conflict areas in Sri Lanka’ (2002), Unpublished.

[19] A. A. M. Nizam, ‘Pilot Project launched to issue Death Certificates of Missing Persons in Sri Lanka’, Asia Tribune (2011), available at: http://asiantribune.com/news/2011/06/27/pilot-project-launched-issue-death-certificates-missing-persons-sri-lanka

[20] Report of the Commission of Inquiry on Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation (2011), Section 9.166, p. 365.

[21] D. Somasundaram, ‘Collective trauma in northern Sri Lanka: a qualitative psychosocial-ecological study’, International Journal of Mental Health Systems (2007), 1:5, pp. 28, available at: http://www.ijmhs.com/content/1/1/5

[22] The Guardian, ‘US embassy cables: Sri Lankan government accused of complicity in human rights abuses’, The Guardian (2010), available at: http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/us-embassy-cables-documents/108763

[23] Report of the Commission of Inquiry on Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation (2011), Section 5.48, p. 166.

[24] i.e. S. Sanaraj who disappeared on June 13th 2013 and K. Niruban who disappeared on September 19th, 2013.