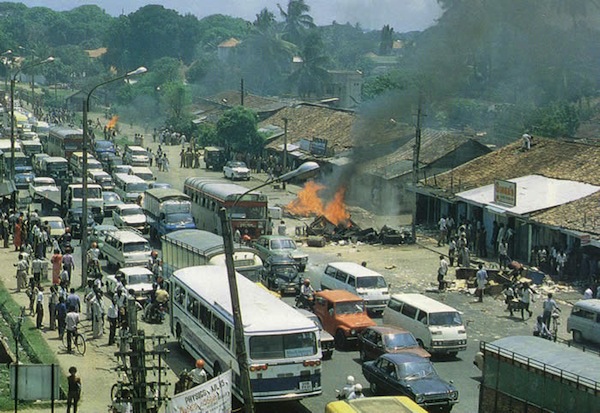

Photo from Sangam.org

These memories still haunt me—even 30 years later. Pain clutches me, along with fear and trepidation. Now I look back and remember with tears of profound sadness at so many things that happened as a result of this fateful day 30 years ago. Things that tore a nation apart, threw my family to the wolves, forced us to leave….and yet we were the lucky ones. We made it out.

My family was just getting to a point where many young families feel comfortable. My father had a good job at Ministry of Ag, with a driver and important meetings that he attended representing Sri Lanka. My mother – she was some kind of important person in the Ministry of Tea Plantations. I knew this only because she had a big office away from the others.

As a result, I too felt important. I thought we were special—my sister and I. I had no idea how different we really were from everyone. You see, we aren’t like all the others. Not because of our house, car, or nice flatware. But because we are a mix of two cultures – that didn’t feel that different to us, but would come to define for the rest of our lives.

My father is Tamil, from Jaffna; my mother Sinhalese, from outside Kandy. They met as lecturers at Peredeniya University. They fell in love and got married (against the advice of their parents). They hoped to raise us in peace, safety, and love. But they were not given the chance. The country that they both loved so much didn’t want their kind… or at least not my father’s kind. And now that my mother had married him – it was her kind as well. And for that, she would never be seen the same way. And after July 1983, never would her life be the same.

That Black July day 30 years ago, my sister and I were picked up early from Bishops. I was in kindergarten, or nursery, and my sister was in Grade 1. We were naturally excited and hopeful for some big surprise at home. But when the driver took us back, we saw things that still haunt me. I don’t remember all of what I saw, but I remember how I felt. Fire, people running, mobs of people gathering. It felt scary. We were happy to get home and find that the house was okay. But there was fire everywhere. Even the house across the street was burning. I was so confused. My parents were on their way home to meet us, so I couldn’t yet ask them what was happening.

And when I ran to our doghouse to let loose our little puppies, they weren’t there. Not even Sheba, the mother. I asked Upali, the boy who took care of the house, what had happened. He said some bad men had come to the house and he had gotten them to leave. But they had taken the puppies and beheaded them. As scared as that made me feel, as horrible as it was, that was only a sign of much worse happening in other parts of Colombo.

I didn’t understand then how incredibly fortunate we were. They had come for my father, for us, and had found nothing and left us alone, this time. But since it was the second time this had happened to my father, for whom the 1977 riots had been much worse, they decided it wasn’t safe anymore. They would have to leave their homeland to start over somewhere far away from the madness.

That week continued to be filled with strange memories. I was young, so my memory is foggy, but I just remember how scared we were. My cousins were in some camp outside town—my cool cousins whom I admired so much. We went to the family of one of my father’s friends; they were safe in some diplomatic housing. We squeezed in with them and their three children to wait it out. It would have normally been fun, except our parents were so scared and worried about us. Only later would I understand why.

The story of my family is, in the end, we escaped. We made it to the U.S. and we survived. We put the awful history behind us and never looked back. Except when, on occasion, I saw a burned-out building and felt sick to my stomach. Or smelled burning rubber – and suddenly wanted to vomit. Somewhere deep inside my child’s psyche, I knew what that smell was: burning flesh. Burning shops. Shops that we used to frequent. Shop owners who had lost everything—sometimes even their lives. Families torn apart. People who had everything, forced to start over with nothing but the clothes on their back.

I remember asking my mother during this time, “Why, Ammi, are they burning our local shop?” What is a mother to say to that? “Well, putha, it’s because the people who own those shops are the same as your father”? What kind of society had we become? We observed such hate, such obscene behavior, that we couldn’t even speak about it afterwards. And for all those who committed the heinous crimes, there were some who risked their lives to save others.

But how, after so long, have we found ourselves back in a world where we pretend as if this never happened? As if the crimes were not actually orchestrated at the highest levels? I still cannot believe that people who watched and applauded killing their own neighbors were never brought to justice. If we do not share our stories, we will just continue to forget. If the survivors are not able to tell their story, who will?

This was my story. We left Sri Lanka almost one year later, in July 1984. We never looked back, but we never forgot the painful lesson either. You never know when everything you have might just be taken away from you. In the blink of an eye. And we were the lucky ones…