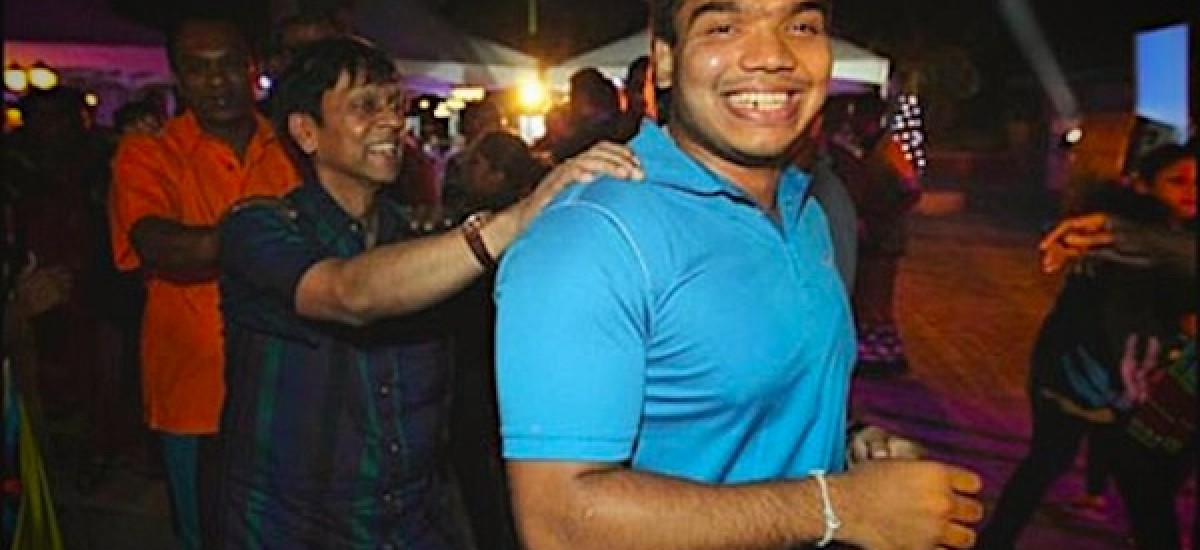

When Sri Lanka vied for the 2018 Commonwealth Games, there was a telling photograph taken at one of the bashes the regime threw in the Caribbean, the culminating event of a labour intensive, extravagant self-indulgent exercise. The photograph has Hon Namal Rajapaksha MP leading a conga line followed by the Governor of the Central Bank. They both seem…well, happy. However, though a good time was had by all no doubt, that conga line led nowhere. We did not win the bid to host the 2018 Commonwealth Games; agnostics and atheists alike were put on notice about the existence of the divine. The country was saved. Yet the conga line as both a metaphor and description of the structure of power and the ruling regime remains. Into 2012, where will it head?

The old year 2011 like all others before was interesting in the sense of the Chinese curse. It saw the steady decline of governance and the Rule of Law, the steady rise of militarization and the interminable decline of the opposition; more attacks on the freedom of expression and association and the re-emergence of disappearances; grease yakkas, plastic crates and the fatal private pension plan; an unnecessary, yet revealing controversy over the national anthem; the release of a COPE report confirming losses by state enterprises running into billions of rupees and at the same time legislation deemed urgent in the national interest to take over underperforming and under utilised private sector enterprises. Sarath Fonseka continued to be harassed and is now to be written out of the history books Soviet-style, including the revamped version of the Mahavamsa; monitoring MPs and presidential advisors fought to the death and probable permanent disability, High Noon style, and in the dying days of the year, a Pradeshiya Sabha chairman alleged to have engaged in fatal political violence during the last presidential election, is now implicated in the murder and serious assault of tourists. There is of course the fiasco of the release of exam results and the sham/e of Sri Lanka Cricket.

Significantly, some 40 years on from the last pre-war election in 1977, one party was overwhelmingly returned in the south and another likewise in the north in local government elections. The regime – TNA talks are more and more reminiscent of the lines from Macbeth – tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow… it is a tale told by an idiot full of sound and fury signifying nothing.

On a positive note, the economy is supposed to be booming. Every index is up – number of tourists, remittances, exports, and foreign direct investment (FDI). Inflation, indebtedness and the cost of living too! The trade deficit remains in billions of dollars despite the increase in remittances, exports, tourists and FDI. The capital city is being beautified – a direct boon of the pairing of defence and urban development we are told and many believe, irrespective of the number of city dwellers who have paid the cost in eviction. There is a highway to the south and an aptly though controversially named Mahinda Rajapaksha Performing Arts Centre with state of the art facilities, as well as night racing to boot.

And there is the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC) Report, the document, which, the regime has maintained, will answer its critics and lay to rest the charge of war crimes and the call for accountability in respect of them. This the Report does not do, thereby lending credence to the criticisms leveled at it in terms of mandate and composition and most importantly, thereby reinforcing the call for international investigation. The LLRC concludes that there was no deliberate targeting of civilians by the armed forces or use of siege tactics by the regime with regard to the provision of food and medicine to civilians in the Vanni. It acknowledges that, “…material points towards the implication of the Security Forces for the resulting death and injury to civilians, even though this may not have been with the intent to cause harm”.

This is largely based on the testimonies of the security hierarchy and suffers from the lack of witness protection, which would have facilitated a more comprehensive account of what transpired. The LLRC makes reference to the technical difficulties in reconstructing what happened and notes the near impossibility of doing so, now. On the key issue of war crimes and violation of international humanitarian law, the report is a whitewash of the regime. This is very disappointing given the urgent need for accountability at the community level in particular, as demonstrated by the number of civilians who testified before the LLRC despite the difficulties and subsequent dangers they faced in doing so.

It is a curate’s egg, however. Its conclusions on reconciliation, the atrocities of the LTTE, militarization, a political and constitutional settlement based on devolution, the politicization of governance, the erosion of the rule of law, the naming of para-militaries and the call for further action on this and on disappearances and detainees as well as the Channel Four documentary, on right to information legislation, are all to be welcomed. All of this begs the question of how any “independent’ or “proper” investigation the LLRC recommends can be done nationally. None of this is new; most of this has been championed by civil society for quite some time. That a regime appointed commission reiterates all of this, underscores both the scale and nature of the challenge the regime faces and accordingly, the scale and nature of the paradigm shift it has to undertake if it is to, as it must, implement these recommendations without delay.

Quo Vadis, the Conga line in 2012? Can the tiger change it stripes; the leopard its spots?

Can pigs fly?