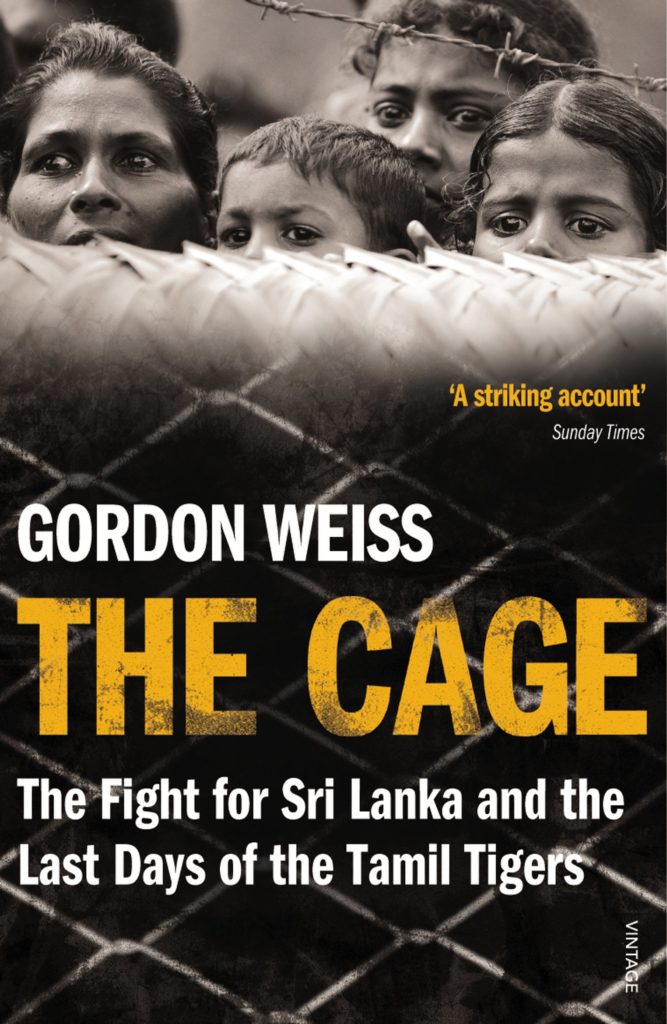

I was elated to take delivery of my copy of The Cage by Gordon Weiss yesterday. Having pre-ordered it off Amazon UK, I fully expected it to be held up by Customs officials in Sri Lanka, given the incendiary issues the book is anchored to and its author, an erstwhile employee of the United Nations (UN) in Sri Lanka. As a friend quipped, they probably thought it had something to do with the Dehiwela Zoo. This may be true for now, but it is highly unlikely, in a country that has repeatedly even blocked issues of The Economist with articles perceived to be against the incumbent government, that this tome will be freely sold in bookstores.

The publication and release of The Cage comes soon after the hugely controversial and deeply distressing report by the UN Secretary General’s Panel of Experts, which found credible allegations of war crimes and crimes against humanity by both the LTTE and government armed forces in the final months and weeks of the war. Just today, no more than 24 hours after I first picked up this book, Kumaran Pathmanathan (alias KP), the former head of the LTTE’s arms procurement department, said in the media that the UN and West were prepared to send in a ship to rescue LTTE leaders towards the fag end of the war[1]. As I sit down to write this, the sonic booms of Kfir jets over Colombo, once a familiar sound, herald preparations for the second anniversary of the end of war. Last year, the President proclaimed that the armed forces did not kill a single civilian and that they “carried a gun in one hand and a copy of the human rights charter in the other”. It is a powerful fiction – simply told and sadly, simply believed. A few days hence, this compelling fiction will drive the proceedings of an international seminar, organised by the armed forces, aimed to share the government’s unique ‘mojo’ of defeating terrorism with the rest of the world[2].

The Cage is a page-turner. Gordon’s prose is lucid and compelling. This is not a book you can easily put down once picked up. There are around 60 pages of notes and background reference material – Weiss has clearly done his homework. The book is anchored to the final few weeks of war, but holds lessons more broadly applicable, and covers issues as diverse as geo-politics and international relations to international humanitarian law and its application in the Sri Lankan context. Weiss is also clearly well versed in the art of communication – for example, demonstrating a rare insight into how to humanise a large tragedy, he compares throughout the book the size of the sand spit where the war ended and tens of thousands of civilians were trapped in to the size of New York’s Central Park, London or Hampstead Heath. This is powerful writing, because it communicates far more effectively the cramped landmass than any figure in square kilometres or miles can.

As I read the book cover to cover in a matter of hours, it reminded me so much of another book – David Blacker’s A Cause Untrue, first published around 2005. As I noted in a review of A Cause Untrue,

“the strength of Blacker’s writing is that it is hugely believable. We know we are reading a work of fiction, but the familiar names, places, incidents – all serve to sharpen the illusion of reality. Intense, thrilling and intoxicating – the Schumacher pace of this book fuels the careening progress of its plot. The thrill, primarily, is in reading the fictional accounts of familiar actors– the Government of Sri Lanka, the Special Forces of the Army, the LTTE etc.”

Weiss does not intend his book to be perceived or judged as fiction. It invariably will be by many. The comparison between Blacker and Weiss is perhaps unfair, but with certain merits. Both books deal with Sri Lanka’s 30-year-old war that ended decisively in May 2009. Both portray, albeit very differently, the Liberation of Tamil Tigers Eelam (LTTE), which at its zenith was one of the most ruthless terrorist groups in the world. Blacker’s fiction renders operatives of the Sri Lankan armed forces like Fleming’s Bond – as suave, raffish international operators. In contrast, many accounts of the armed forces in The Cage are ferociously barbaric, visceral. Just as much as I observed that Blacker’s work intersperses the real with the fictional, many sections of government, the armed forces and even the UN in Sri Lanka and New York will see Weiss as a talented but tainted author of a book that isn’t pegged to any evidence on the ground.

Sadly, some of the irresponsibly written and edited content in The Cage will support this response. Weiss notes that his first introduction to Gotabaya Rajapaksa – who is featured extensively in the book – was just after the suicide attack against him in December 2006[3], stating that it was a Mercedes that saved his life. It was in fact an armour plated BMW 7 Series that saved Gotabaya’s life and ironically, one that the former President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunge imported to Sri Lanka[4]. On page 6, Weiss notes that on the day Prabakaran’s death was announced through the media, “there was little of the air of celebration one might have expected at the end of such an epoch”. I do not know which part of the country Weiss was at this time but it was one big, riotous party in and around Colombo on the 18th of May[5] and extending for the most part of a week. On page 145, Weiss asserts that Sri Lanka’s current Foreign Minister, G.L. Peiris, was in May 2010 the Attorney General. He never was – Weiss confuses Mohan Peiris with G.L. Peiris. There are other revealing ambiguities, over for example the portrayal of the Sri Lankan armed forces. On Page 180, quoting an article that appeared in the Hindustan Times by Suthirto Patranobis, Weiss avers that an ‘unnamed Indian doctor’ said the true death toll had been ‘brushed under the carpet’. Weiss could have researched this better. The Indian doctor does in fact have a name – he was Dr. Tathagata Bose, and before the Hindustan Times report, the first we heard of his observations treating those coming out of the war zone was on Groundviews, where he said “If an infant could not be protected, imagine the plight of older children and adults. The so-called ‘Sri Lankan Solution’ being touted as the panacea for dealing with terrorism worldwide needs a thorough relook.”[6] Page 186 is nearly entirely devoted to high praise of Sri Lankan doctors working in the front-lines during the end of war in horrific conditions and the kindness of front-line soldiers. As Weiss avers,

“During the course of research for this book, dozens of Tamils described the Sinhalese as inherently kind and gentle people. The front-line soldiers who received the first civilians as they escaped to government lines, those who guarded them in the camps and the civilian and military doctors who provided vital treatment distinguished themselves most commonly through their mercy and care.”

Further on in the book, Weiss gives examples of soldiers who tried their utmost to distinguish between LTTE combatants and civilians in incredibly confusing and stressful ground conditions, gave up their own rations to feed those who were dying of hunger in the internment camps established by the government just after the war and other incredible stories of compassion and mercy towards injured Tamil civilians – mothers, children, infants and men – in the hellish last weeks and days of war. This ostensibly echoes what for example Brigadier Prasanna de Silva from the 55th Division says in the film directed by Guy Guneratne The Truth That Wasn’t There[7]. However, Weiss also then unequivocally asserts that “this does not mean that soldiers did not directly kill thousands of civilians in the heat of combat” and notes that “… Survivors testify that advancing soldiers lobbed grenades methodically into bunkers that often held civilians.” Gordon’s attempt to portray the armed forces through a wide-angled lens of complex emotional, psychosomatic and combat responses to war is commendable, and indeed, more rounded than what most other writers, including those in civil society, have penned to date. It is sadly a leitmotif left abandoned in the book. Weiss offers no larger analysis of this tragic fragmentation between spontaneous compassion and calculated mass scale atrocity, and its affects on the civilians caught in direct or cross-fire.

Sections of The Cage therefore will be flagged as authentic by government, most other passages, violently derided as conspiratorial fiction. Unsurprisingly, given the reaction to the UN Secretary General’s report, the sections the government will be most upset by and why this book will never be openly sold in Sri Lanka will be those dealing with ground conditions in the Vanni from around January to May 2009 in particular, plus the content on page 225, dealing with the assassination of the LTTE’s leadership even after the conditions and path of surrender had been worked out with those in government.

The vociferous support of the UN Secretary General’s report by many sections of the pro-LTTE Tamil diaspora is pegged to its repeated and deep consternation over instances where government armed forces actively targeted civilians. What the UN report also makes explicitly clear and Weiss in The Cage repeatedly underscores are the unimaginably barbaric actions of the LTTE “to fire artillery into their own people” based on “the terrible calculation that with enough dead Tamils, a toll would eventually be reached that would lead to international outrage and intervention.” Here’s the rub – with their leadership decimated, there’s no one in the LTTE to hold accountable.

Not so with the armed forces.

Chapter Five (Convoy 11) is a damning indictment of the Sri Lankan armed forces. Weiss quotes at length eye witness testimony and the experiences of two military men – retired colonel Harun Khan from Bangladesh and the UN’s security chief Chris Du Toit from South Africa, also a retired colonel. The chapter is based on their experience of accompanying the 11th WFP food convoy into the Vanni. It is a mind-numbingly harrowing account of violence that supports what the UN Panel of Experts says are credible allegations of war crimes and crimes against humanity. Weiss takes pains to emphasise that the appalling details are based on reports by two men who each had significant experience in active combat. Throughout the chapter it is made very clear that the Sri Lankan armed forces were driven by the single-minded pursuit of decimating the LTTE. As Weiss notes regarding the establishment of the so-called No Fire Zones (NFZs), “The decision to unilaterally declare an NFZ in that particular location, hard up against an unpredictable and eroding front line had little to do with protecting civilian lives and everything to do with their removal as an obstacle to unrestrained firepower” and goes to say that “… it was reckless and dangerous strategy that had everything to do with political expediency and little to do with the duty of care owed by the government to civilians. It also said much about how the Sri Lankan leadership valued the lives of the ‘Tiger’ civilian population”. The Sri Lankan armed forces, in sum had towards the end of war become a mirror image of the terrorist group they were fighting against. Pages 116 – 120 are, simply put, difficult to digest even after reading the macabre details published in the UN’s own report and others from Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch. Weiss speaks of photographic evidence of the carnage taken by Col. Khan, but there is none to be found in the book itself. Dismembered babies may have been too gruesome to include in the tome, but are photographic evidence of the deliberate targeting of civilians. Weiss does not say who has these photos, but we can assume, amongst others, the UN does. The Cage goes on to deal with what is now, sadly, the well-known shelling of the PTK hospital guided by what Weiss claims “to be the result of a frantic SLA push to seize the town before Sri Lanka’s annual independence celebrations on 4 February”. On page 133 Weiss calls out the mentality of the government and the armed forces towards the end of the war, which believed “that the failure of civilians to make the perilous crossing of the front lines in effect amounted to complicity with the tactics of the Tamil Tigers.”

The Cage then, though in form different to the UN Panel’s report, supports the same significant concerns over war crimes committed by the armed forces and the LTTE. There is however one other development that arises from this book’s publication when juxtaposed with the official version of the UN Panel’s report, released late April. The justifiable caution over and confidentiality of sources in the UN Panel’s report is ruined by the revelations in The Cage, attributed by Weiss to specific individuals. Pages 23 to 24 of the UN Panel’s report, in particular sections 83 – 89, also deals with Convoy 11’s experience. No names of the sources however are given. After reading The Cage, it is a matter of simple extrapolation that the sources were in fact Col. Khan and Col. Du Toit. It is unclear how the UN itself will respond. Weiss makes it clear that those accounts that are attributed to individuals was done with explicit permission. The situation reports they would have submitted to WFP and other UN agencies would obviously have informed the Panel’s report. What Weiss has unwittingly done here is to add fuel to the government’s propaganda machine and its most vicious, voluble proponents. It also runs counter to the author’s own assertion (page xxix) that he has done his best “… to interpret and use publicly available information, and has not drawn on confidential correspondence or internal reports, discussions…”. I pride myself on being rather well informed about what is in the public domain dealing with the end of war, but cannot once recall or find any record of what Du Toit or Kahn refer to in The Cage outside of the book, or published anywhere before it.

Annoyingly, The Cage also features the off-handish inclusion of disturbing allegations. On Page 211, Weiss passingly mentions the use of phosphorus shells exploding amongst civilians. This is in fact an extremely serious allegation, and though it has also been reiterated in Tamil media in Sri Lanka, it is one that the government and the armed forces have vehemently denied[8].

That said, The Cage is much more than the narration of carnage so violent, that it defies easy comprehension. Weiss’s book is an attempt to contextualise this violence in the history and ethno-politics of Sri Lanka, and here he succeeds better than most. Weiss calls himself ‘an informed observer’ early on in the book. At the beginning he asks several questions – and vital ones at that – on whether the Sri Lankan government had any alternative to what they ended up doing to end the war. This book is a scathing critique of what the author sees, and those like Louse Arbour also agree as the UN’s “complicity with evil”, but no more so than the report by the UN Secretary General himself. Some soul-searching has been promised, but it is clear that it will take time and will involve problematic investigations into the culpability of highly placed officials in the Secretary General’s cabinet, the resident representative of the UN in Sri Lanka at the time and heads of other UN agencies. The strongest condemnation however is directed at the armed forces and government. Weiss on page 145 (and again on page 197) offers an alternative denouement to the war, though noting that it is now impossible to determine how the government would have reacted to a UN system more proactive in its condemnation of civilian deaths. The alternative proposed by Weiss is interesting reading, but utterly divorced from the (Sinhalese) mentality and sheer hatred of the LTTE that drove government and the armed forces, who having whiffed the decisive end to the war through the decimation of the group’s leadership, weren’t interested in anything or anyone that stood in their way.

Tellingly, the resulting gory and for example the unearthly conditions of Menik Farm remain, at best, of peripheral interest to the majority in Sri Lanka. They are issues and people out of sight, out of mind. The Cage will have about as much impact in Sri Lanka as banning issues of The Economist. Dozens of copies of the book will invariably make its way into Sri Lanka. Much like my own copy, they will be passed on from hand to hand to inform a few concerned about war crimes allegations and are in favour of robust, independent investigations into such allegations. Internationally, The Cage will guarantee it’s author a slot in the literary festivals circuit (sans the Galle Literary Festival) for the next year at least, coupled with media interviews, reviews such as this and op-eds to plug the book – all of which will keep the spotlight on Sri Lanka’s tryst with war crimes. Will this result in any demonstrable change in Sri Lanka? I think not.

If anything, The Cage is more than a disturbing scrutiny of the final phase of war. Weiss also flags in some detail a corrupt, dysfunctional judiciary and the erosion of democratic governance, even before the 18th Amendment. In highlighting the murder of the fifteen aid workers in 2006, Weiss underscores what Amnesty International has also clearly flagged – no commission of inquiry or process of investigation into killings that have involved the State has brought the perpetrators to book. The Cage looks the significant role China played in the guarding Sri Lanka against UN condemnation and sanctions both in Geneva and at the Security Council in New York as well as supplying the armed forces with weapons. The author places Sri Lanka centre and forward in the new ‘Beijing Consensus’, and sees China’s complicity with the war’s end as the building block of deep and lasting economic partnerships over the coming years. The considered position of an informed observer gives Weiss a unique vantage to see how the systemic decay within Sri Lanka, coupled with the shift of geo-political advantage to the East in international fora played into the carnage in the Vanni.

For me, it was a single sentence in The Cage that captured the tragedy of war’s end, and how it has so violently defined our country. It wasn’t anything to do with the effects of shelling and shooting point blank children, lactating mothers or the elderly. It wasn’t about the entrails that adorned burning landscapes after the shelling ended. It wasn’t in fact anything to do with the violence rent by arms. Page 185 deals with how even in sheer destitution and despair, civilians in makeshift camps sandwiched between the armed forces and LTTE tried to make the most of their perilous condition. Weiss notes that ,

“There was a shortage of material for everything, and people were compelled to use their colourful, expensive wedding saris, which usually handed down from mother to daughter.”

For most Sri Lankans and especially for Tamils, this is an image extremely resonant and more than a little saddening. This tragic loss of dignity and identity to just survive through the night are not wounds that heal easily. This loss of what it means to be human is not regained by the year on year growth of GDP or the increasing influx of tourists. During the war, the government perceived all Tamils as LTTE, even in Colombo[9]. After the war, nothing – nothing at all – of what the government has done meaningfully addresses legitimate grievances that gave rise to the heinous entity that was the LTTE. From the violence of the 18th Amendment to that of government ministers in Jaffna[10], the treatment of those interned in Menik Farm, the wasteful and outrageously insensitive celebrations over the second term of the President[11], the millions of dollars the government spend son bids for the Commonwealth Games and entities like Bell Pottinger to whitewash its name[12] and yet can’t spend on those uplifting the livelihoods of those most affected by war, including families of armed forces personnel killed or MIA – these and so much more of what the Rajapaksa regime does suggests we are all hostage in a cage much larger than what Weiss flags in his book, and arguably harder to fight against and escape from. The necessary opiate to keep inconvenient questions and truths away from public scrutiny remains a language of hate and harm – viciously denying, decrying, defiling and denouncing anyone, in Sri Lanka or outside, who questions the President’s assertion, parroted by his brothers, government and unprincipled schmucks in the UNP that no war crimes were committed by our armed forces.

In January 2010, the discerning Sri Lankan voter faced a horrible choice in selecting a viable post-war President. Equally egotistical and megalomaniacal, Mahinda Rajapaksa and Sarath Fonseka represented the girders of this larger cage. One won, the other lost more than expected, but indirectly or directly, they are both responsible for allegations of war crimes and crimes of mass atrocity against our own people. These are allegations that will certainly not result in any quick regime change, but are as unlikely to ever fade away. They will keep coming back, again and again and again. Until and unless there is a meaningful process of truth-seeking and truth-telling, we risk losing out on the verdant democratic potential of our country post-war and a descent into what Weiss ominously notes in the final sentence of The Cage as a “tyranny where myth-making, identity whitewashing and political opportunism have defeated justice and individual dignity.”

The Cage is published by Bodley Head, Random House and available at the time of writing on Amazon UK.

[1] How the UN and West made one last effort to rescue LTTE leaders in May 2009, http://www.firstpost.com/politics/how-the-un-and-west-made-one-last-effort-to-rescue-ltte-leaders-in-may-2009-2-14370.html

[2] Seminar on defeating terrorism: Sharing Sri Lanka’s experience, http://groundviews.org/2011/05/16/seminar-on-defeating-terrorism-sharing-sri-lankas-experience/

[3] Defence Secy escapes LTTE assassination bid, http://www.dailynews.lk/2006/12/02/sec01.asp

[4] Row over Sri Lanka limos, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/942796.stm

[5] The celebrations in Colombo after Prabhakaran’s demise, http://groundviews.org/2009/05/19/the-celebrations-in-colombo-after-prabhakarans-demise/

[6] See full comment at http://groundviews.org/2010/05/20/i-remember-–-19-may-2010/#comment-19357

[7] In 2009 three young filmmakers crossed the frontlines in the wake of civil war in Sri Lanka. In doing so they became the first independent journalists to visit the final battlegrounds. See https://www.facebook.com/tttwt

[8] On 20 September 2010, the Tamil newspaper Sudar Oli quoting the testimony given by N. Sundermurthi to the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC) also noted the use of phosphorous bombs. As noted by Sundermurthi, “The LTTE even attacked airplanes that were sent to attack the safe zones. When they counter-attacked, the Army used banned phosphorus and cluster bombs against the LTTE. There were many casualties on account of this. Around 400 – 600 died daily, and around 1,000 were injured. It was a grim situation. After this, amidst incredible hardship, we arrived in areas controlled by the Army.” See http://groundviews.org/2010/09/24/did-the-sri-lankan-army-use-cluster-bombs-and-phosphorus-bombs-against-civilians/ for a translation by Groundviews of this disturbing Tamil news report.

[9] Expulsion of non-resident Tamils from Colombo, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Expulsion_of_non-resident_Tamils_from_Colombo

[10] Anti-UN sentiment in Jaffna: Fact or fiction?, http://groundviews.org/2011/05/09/anti-un-sentiment-in-jaffna-fact-or-fiction/

[11] Record-breaking rice cakes, but at what cost?, http://groundviews.org/2010/11/19/record-breaking-rice-cakes-but-at-what-cost/

[12] Bell Pottinger and Sri Lanka: Millions spent for what?, http://groundviews.org/2010/03/24/bell-pottinger-and-sri-lanka-millions-spent-for-what/