Due to Sri Lanka’s geographically strategic location coupled with its natural and economic resources the absence of war will give us a chance to move in the direction of a vibrant South Asian economy based on a fiscal program concentrating on exports, tourism, self sufficiency and Post War infrastructural development. However, this cannot be achieved by one section of Sri Lankan citizens alone and it will take inter community cooperation and coordination for Sri Lanka to emerge into its true potential. Hence, it is essential that we are sensitive to ethno political and social grievances when we work towards a climate in which all Sri Lankans can share the benefits of economic and infrastructural development.

The real question we should be asking ourselves right now is whether we can create more opportunities for ourselves to establish a sustainable peace with the end of war in Sri Lanka by creating a culture of inclusiveness, equality and respect for all communities in the motherland. A broader, stronger and longer homegrown reconciliation process will be a good ‘first step’ in this direction.

Two ‘universal’ theoretical underpinnings should be taken into account in any Sri Lankan post war reconciliation process. Firstly, learning our lessons from the last 30 years of war and 60 years of conflict must be based upon the twin reconciliation principles of promoting historical revisionism over denial and minimizing cultural dissonance. For the stability of our country and future of our children it would bode well for all Sri Lankan citizens to work towards upholding and utilizing these two principles as a basis for learning lessons from the past during a reconciliation process. Secondly, there must be a focus on improving social cohesion during a post war reconciliation process. Hence positive and negative social cohesion trends could be used as indicators to monitor the health of a reconciliation process. If we take these concepts into account when designing a practical and inclusive truth and reconciliation process we may be able to build a more stable peace in Sri Lanka. This is no simple matter and it will have to be examined in greater detail then what is presented in this article. However, it is important that all citizens exchange our ideas on how we can live together peacefully in this country and this article attempts to get the ball rolling on this discourse. Hence, let us start with the two basic principles.

Two Reconciliation Principles

If we only look at one side of the past or if we look at the past from only one perspective, chances are high that we will miss critical aspects through which we could learn lessons for the future. Historical revisionism entails the refinement of existing knowledge about a historical event without denying that the event itself took place. Refinement comes through the examination of all empirical evidence by accounting for all knowledge about a particular historical event in a ‘better light’. We must be able to acknowledge a body of convergent indisputable knowledge in a manner that helps us to understand whether a historical event did occur in the manner that it did. This form of legitimacy is essential in a post war reconciliation context. Denying historical events and the manner in which they occurred rejects the entire foundation of historical evidence and is thus detrimental towards building social cohesion on the long term. Hence, we must promote historical revisionism over denying what happened in the past. The Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission is a step in this direction, but it must be made stronger and allowed to operate for a longer period of time.

Cultural dissonance is an uncomfortable sense of discord, disharmony, confusion and conflict experienced by people in the midst of a changing cultural environment. There are three root causes for cultural dissonance to increase and they are all best on ‘change’. Firstly, to a particular community social, political or economic changes could be seen as unexplained. Secondly, these changes could be seen as unexpected. And thirdly, these changes may be perceived to be not understandable. Hence, everyone must be given the opportunity to explain, understand and then expect ‘change’. Hence, it is essential to have a reconciliation process that will minimize cultural dissonance by giving all people the opportunity and access to present their own perspectives on critical reconciliation related issues. Furthermore, such an opportunity will also give people the right to experience different perspectives thus creating a chance for people to build a more socially cohesive configuration. In the present context, only the Sri Lankan State has the capacity to evolve strong mechanisms that will create the space and legitimize the right of its own citizens to present their perspectives on a reconciliation based issues. What it lacks is the will to move forward on genuine reconciliation and only the people can foster such a ‘will’ in the Sri Lankan state.

Taking these principles in tandem will ensure that a reconciliation process based on learning lessons from the past will aid us to understand the ‘truth’ about what happened in the past in a more practical sense. It will be a painful process but if we really want sustainable peace we will have to face the violent demons of Sri Lanka’s past.

Social Cohesion as an Indicator of a Reconciliation Process

In a situation of cultural diversity, social cohesion is a term used to describe socio dynamics that increase positive social interactivity between people in society. The definition of social cohesion is broad because it is a multifaceted notion covering different types of social phenomenon. While the definition is broad the indicators that are used to monitor basic human needs in relation to social cohesion are much clearer. Hence, positive or negative trends in relation to social cohesion can be utilized as indicators of whether socio – political relations between different groups are good or bad. There are five different dimensions of social cohesion:

Material conditions: Are fundamental to social cohesion, particularly employment, income, health, education and housing. Relations between and within communities suffer when people lack work and endure hardship, debt, anxiety, low self-esteem, ill-health, poor skills and bad living conditions. These basic necessities of life are the foundations of a strong social fabric. They are also indicators of social progress.

Social Order: Is mainly in relation to safety and freedom from fear, or “passive social relationships”. Tolerance and respect for other people, along with peace and security, are hallmarks of a stable and harmonious society.

Positive interactions, exchanges and networks between individuals and communities: Is mainly in relation to the quantity and quality of contacts and connections between individuals and communities which become potential resources for places since they offer people and organizations mutual support, information, trust and credit of various kinds.

The extent of social inclusion or integration of people into the mainstream institutions of civil society: Including people’s sense of belonging to a state that is based upon the strength of shared experiences, identities and values between those from different backgrounds.

Social equality: Is in reference to the level of fairness or disparity in access to opportunities or material circumstances, such as income, health or quality of life, or in future life chances. It is possible to utilize material conditions indicators for this purpose but the emphasis here is upon any form of disparity in material conditions between different community groups.

In addition to these 5 dimensions there are an additional number of sub dimensions in each of these 5 dimensions which are indicators in relation to the positive or negative dynamic of each trend. These 5 dimensions and their sub dimensions can be utilized as a basic framework to monitor or promote social cohesion in a reconciliation process. I could not include them here because it would have elongated this article, but they can be discussed and researched further if it is needed. When taken as a ‘whole’ these social cohesion dimensions can be used as a Social Cohesion Matrix, reverse engineered to suit the Sri Lankan context. We could then adopt this framework to design and monitor social cohesion during Sri Lanka’s reconciliation process. However, it must be very humbly said that this is only a basic framework which must be expanded through dialogue.

A Homegrown Sri Lankan Reconciliation Process

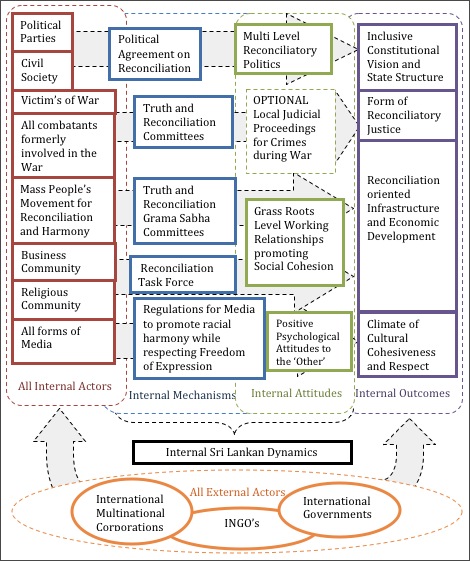

Utilizing historical revisionism over denial and the minimization of cultural dissonance as a principles in the design of a reconciliation process for Sri Lanka would increase the chances of sustaining such a process and reduce the chances of long term conflict re escalation. By monitoring any aspect of the reconciliation process utilizing social cohesion as an indicator we would at least be given the opportunity to asses, compensate and reorient different aspects of the process. However, the most important issue in a homegrown Sri Lankan reconciliation process would be whether the process itself can synergize with contextual factors, actors and dynamics in the Sri Lankan socio political environment. Therefore there should be five contextual areas of importance in relation to such a process: (1) All Internal Actors, (2) Internal Mechanisms for Reconciliation, (3) Internal Reconciliatory Attitudes, (4) Internal outcomes from the Reconciliation process and (5) All External Actors. None of these areas are ‘set in stone’ they are fluid and interchanging at many levels. They represent only a proto stage set of proposals for a broader, stronger and longer Sri Lankan reconciliation process which must be designed through the interaction and participation of all Sri Lankan citizens. A very basic representative diagram is available in order to visualize what it could look like.

However, the real fact of the matter lies in the hearts and minds of our people. Do we really want to reach out our hands to people who believe to be our significant ‘other’? Can we really get over years of bloodshed and violence? Can we really forgive ourselves and the people who committed violence against us? The answers to these questions lie in the future. But the course of action we take depends upon you and how you can influence our leaders, our state and our beloved motherland towards a greater and brighter future. My appeal is that we do not let this opportunity slide away from us. No war, no peace nor end of war is perfect. It is only in the purity of thought in pursuing peace, respect and harmony between communities that we can reach perfection. This article represents the tip of an iceberg representing a younger generation battered and scarred by years of war. The chains of communal ignorance will not bind us further. One day, we will rise together by not only respecting our differences but enjoying them in a deeper respect for each other. Our future is already written. It is inevitable and the only choice left to us is whether we wish to start the true process of reconciliation now or later.