At my local hospital (in the UK) this morning, a nurse asked: “If you don’t mind my asking, what is your race?” Not the sort of everyday question, so I was taken aback. “Different races have different risks, you see”, she quickly explained. “Oh, I am Sri Lankan”, I replied. But is that a race? Aren’t we Sinhala, Tamil, Muslim etc. for this race purpose?

From a DNA point of view, Sri Lankan is probably my race. A random subset of Sri Lankans will have the same statistical variation in their genomes, as a group of a particular ethnicity in Sri Lanka. Our genomes are quite a soup: Of indigenous islanders, invading thugs, fishermen in transit and travelling businessmen who retired to stay. My own ancestors were probably thugs, given I can neither catch fish nor do business. (The similarity in medical risk the nurse was concerned with probably has more to do with common lifestyles of immigrants than with genetics.)

Medicine aside, I wondered when I was first asked for my race / nationality and I replied: “Sri Lankan”. It is always a good exercise to flashback at your earliest memory of something. Sharpens your mind and delays the onset of Alzheimer’s.

“When did you first become aware of your penis?” a lecturer at Peradeniya once asked us, a group of undergraduates. University rules do not usually allow such a question. But the lecturer was a philosopher. Also, I had just cracked that silly joke about God being a civil engineer from the Public Works Department: Who else would run a toxic wastepipe right in the middle of a recreation area? “I always knew I had it – and functionally perfect too, thank you very much”, was my aggressive reply to the philosopher. We engaged in a lengthy debate about what he meant by “become aware”. In those lovely surroundings of Peradeniya, with its peaceful looking mountains, winding river and beautiful trees, my philosopher friends could stretch your mind as much as the complex calculus of electromagnetic wave propagation could — albeit in an entirely useless way.

Talking of Peradeniya, I once asked my late father what his flashback of university memories were. A rather crooked character who was my dad’s class mate, upon graduating with considerable struggle, had applied for an inspector position in the police. Bosses there requested the then Vice Chancellor at Peradeniya, Sir Ivor Jennings, for a reference on this chap. “It is my firm belief, considering the interests of society”, Sir Ivor is rumored to have written, “this gentleman is best kept inside the forces than let loose on the outside”. So it seems the foundations were laid long ago, by a celebrated educationist (and sudda – patriots, your chance), for the shameful drama our country enacted at the beaches of Bambalapitiya a few weeks back.

Getting back to my flashback, my first ever declaration of being Sri Lankan nearly landed me in trouble. I was 15 then, and had gone to the Post Office at Bandarawela to get an identity card to sit my GCSE O/L.

I need to clarify the context for you. In the early seventies, Sirimavo had won the elections, the first of the JVP uprisings had been brutally put down and we had declared ourselves a Republic. (Just a Republic then, the “Democratic Socialist” part was added when we decided to be neither – power ever more centralized; gulf between rich and poor ever wider.) No more citizens of Her Majesty, not even a ceremonial Governor, Supreme Court is our own and Supreme. That was all very exciting in my teen-age days.

In recognition of the Republic, I had declared myself a Sri Lankan Tamil, strictly in that order: Sri Lankan first, Tamil second.

After careful analysis, I had even developed my very own teen-ager model of the Banda-Chelva pact: Hire some thugs to beat up Tamils, Banda gets votes in the South, Chelva gets votes in the North. “What do these teen-agers know about real politics”, you reject. Or do you?

At the post office, I filled the form in. Where it asked for nationality, I wrote Sri Lankan. Correct answer, you will readily agree.

The Post Master, however, had a different take. “You should write Ceylon Tamil”, he suggested. He was a very nice man I recall, clean shaven, dressed in full white and spoke good English. A well trained civil servant.

“But I am Sri Lankan”, I protested.

“Ceylon Tamil, you write”, he said firmly.

There was a stand-off. I wasn’t prepared to give up my nationalism. He wasn’t going to deviate from his civil service training. The sleepy post office in that beautiful up-country town has never experienced such tension. But it lasted just for a few seconds though.

I quickly realized I wasn’t going to win this and backed down. Sitting my exam was more important than making a petty nationalistic stand, no?

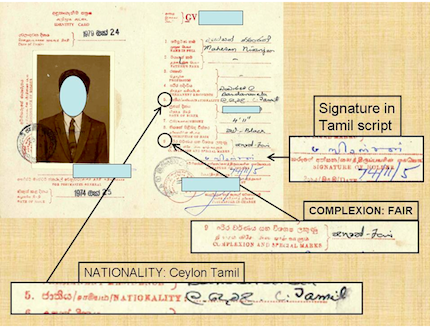

So I filled the form all over again, this time writing “Ceylon Tamil” against nationality. But I made it a point to record my protest by signing it in Tamil script. It was my way of saying “I belong here”.

The habit that started then has stayed with me ever since. Thirty five years on, I still sign my name using Tamil script. Every time I sign, I remember the nice Postman Perera and his innocent attempt at disallowing me membership of my country.

The signature has distorted significantly over the years, and I have invented a kind of flowing-hand writing for Tamil, but still recognizable Tamil characters.

In the mid eighties, before the chip ‘n pin type credit cards were invented, we used cheques a lot. I would go into random petrol stations in London, and often find a South Asian looking young guy working there. Illegal, asylum-seeking Ceylon Tamil guy who ran away from Sri Lanka – fearful of the war or for economic betterment, who knows? The guy would look at my signature on the cheque, compare it to that on the back of the guarantee card and, recognizing the Tamil font, would greet me with a smile and seek to confirm our common race: “Siri Langaavaa?”