Intellectuals in India have unfortunately not played positive roles in building good relations with its small neighbors. For the most part they ignore all neighbors other than Pakistan. In the few cases they do not, they tend to do active harm. The recent article in Forbes.com on 9 October 2009 (http://www.forbes.com/2009/10/08/tamil-tigers-rajiv-gandhi-opinions-contributors-sri-lanka.html) by Professor Brahma Chellaney exemplifies the latter.

Justifying cross-border terrorism

India is a country with many minorities. Would it like an external power describing one of its minorities as its “natural constituency” as Professor Chellaney does? I do not know quite what to make of this excerpt from his article: “India already had alienated the Sinhalese majority in the 1980s, when it first armed the Tamil Tigers and then sought to disarm them through an ill-starred peacekeeping foray that left almost three times as many Indian troops dead as the 1999 Kargil War with Pakistan.”

Was the alienation of the Sinhala majority a good thing? Was the alienation caused by the arming of the Tigers? Or, was it caused by the failure to disarm them? Or both? Is the author justifying the arming of a deadly group of terrorists who pioneered the art of suicide bombing and decrying the effort to disarm them?

I will simply change key words in the above excerpt and invite the reader to reach his/her own conclusions: “Today, [Pakistan] stands more marginalized than ever in [India]. Its natural constituency–the [Muslims]–feel . . . betrayed . . .. [Pakistan] already had alienated the [Hindu] majority . . . , when it first armed [Kashmiri terrorists] . . . .”

Pakistan is not 50 times the size of India, but the government and people of India decry cross-border terrorism. Does Professor Chellaney justify cross-border terrorism as practiced by Pakistan?  Is he able to distinguish between that practice and what India did, by his own admission, to a tiny and powerless neighbor in the 1980s?

If he is correct in saying that all ethnic groups in Sri Lanka are alienated from India (which conclusion I do not share), it is clear that the causes do not lie far. It is the words and actions of people like him that have caused alienation and put India’s many friends (like me) on the defensive when discussing relations with India in their own countries.

To balance the realpolitik-driven Tiger sympathies displayed by Professor Chellaney, a few words need to be said about what the Tigers have wrought. They decimated or drove into exile the entire intellectual, political and cultural leadership of the Sri Lankan Tamils (the dead include Foreign Minister Lakshman Kadiragamar, MP and peacemaker Neelan Tiruchelvam, Former Leader of the Opposition A. Amirthalingam, Public Intellectual Rajani Rajasingham; the list is too long to present here) and left their people leaderless in the aftermath of the conflict. Through their intolerance and casteism, they drove the cream of Tamil society into exile. This was their greatest crime.

They killed off the cream of the southern political leadership, Sinhala and Muslim. Rajiv Gandhi was not their only victim. They killed senior government officials, even those dealing with purely civilian matters. They killed successive mayors of Jaffna, one being a woman they had widowed. She had refused government security saying she needed none among the people who elected her.  The Tigers walked in and killed her in her own kitchen.

The Tigers machine-gunned worshippers in mosques (147 killed) and mowed down old women meditating at the Sacred Bodhi Tree (146 killed; 85 wounded). The per-capita loss of life from their bombing of the Sri Lanka Central Bank (90 killed; 1,400 injured) was larger than what the United States suffered when the World Trade Center was brought down. Sri Lanka’s World Trade Center was attacked before the WTC in New York City was. We lived through many iterations of the siege of Bombay. The only difference was that our tragedies were not televised.

The Tigers prevented the economic growth that Sri Lanka experienced in the past 30 years from reaching the people they claimed to protect. They ripped out the railroad that connected Jaffna to the rest of the country and built bunkers with the ties, also known as “sleepers.” I was shocked by their ignorance and disinterest when I went to Kilinochchi during the ceasefire on behalf of the government to talk to the LTTE’s de facto administration about taking modern communications and the Internet to the Wanni.

I believe that there is appreciation, and indeed gratitude, among public intellectuals, if not the population as a whole, of the positive contributions made by India to ending the scourge of Tamil Tiger terrorism. The supply chains could not have been disrupted without Indian intelligence. People know that an Indian life was sacrificed when the LTTE attacked the radar station in Anuradhapura in the last few months of the war.

The story of Indian military support is not unblemished, however. When the government sought Indian help after the fall of Elephant Pass in 2000, what were offered were ships to evacuate the troops from the Jaffna peninsula. The leadership provided by General Janaka Perera (possibly assassinated by the LTTE) and the multi-barrel rocket launchers procured from sources other than India (including Pakistan) made the Indian offer irrelevant. Contrary to the lukewarm response at that nadir of the war, we do appreciate the concrete assistance provided in Eelam War IV.

Detention camps

Does this mean that I absolve the Government of Sri Lanka from the accusations of egregious violations of human rights that have been directed by Professor Chellaney and others? Definitely not. Despite enormous pressures, public voices have been raised in the South, from the Leader of the Opposition down, against the detention camps in the Wanni.

But in the spirit of realpolitik that Professor Chellaney seems driven by, let me explain the initial decision to move the former inhabitants of the LTTE-controlled areas to camps. My fight, and those of many other critics, with the Rajapaksa government is not about the original decision to send people to camps, but about the decision to detain non-combatants beyond a few weeks.

The numbers are large, I admit. Professor Chellaney says we have interned the equivalent of the population of Belfast; I say we have put the equivalent of the entire population of the Maldives behind wire. But this must be seen in perspective. The Pakistan Army’s sweep through Swat Valley displaced more than a million civilians.

In Pakistan they did not (and do not, in the current operation in South Waziristan) move displaced civilians into camps. Sri Lanka did, and takes the blame. Bombings against civilian and military targets have increased across the length and breadth of Pakistan after the Swat Valley operation; in Sri Lanka, a country plagued by bombings prior to the decapitation of the LTTE by the Nanthikadal Lagoon, there has been only one since the end of military operations. Is there a correlation?

It is well known that hostage-takers escape by mingling with hostages at the end of a hostage rescue. The line between combatant and civilian is a fuzzy one. One, who is a combatant when the war is going well quickly transforms to a civilian when the tide of war turns. Is it possible that the Swat operation allowed the Pakistan Taliban to spread their fighters across the country, only to be supplied by explosives and orders later to do their nasty work?

The Sri Lankan military prevented this outcome through internment (nothing new: the British did it in South Africa, the American did it during the second world war . . . ). But always, security considerations must be balanced with political and human-rights considerations. The government is definitely at fault for not completing the screening for military operatives quickly and letting the majority of the internees go to their relatives or former homes. The demining excuse is patently hollow. The real reason is the lack of people with enough backbone to argue against the security-above-all people in the councils of state. Many voices have been raised in the weakened public fora of Sri Lanka, but that has not been enough. Sustained pressure from within the country as well as from engaged parties such as the Government of India are essential to get more people released as quickly as possible.

China v India

Now, the China question. Yes, there is a real contest going on in Sri Lanka, among other places, between the democratic ideals of India and the business-at-any-cost strategies of China. It is real and serious. It is reasonable for the government and people of India to want to win this contest. But this can only be done through political, economic and cultural engagement that respects the sensitivities of the people who are the objects of the contest, not by hypocritical words and actions.

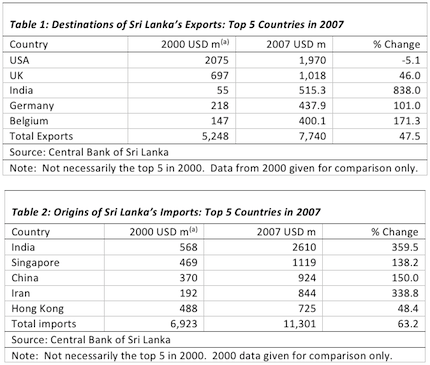

India has the foundation to succeed with Sri Lanka, in terms of trade, investment and even movement of people between the countries. It became the third destination for exports by 2007. For many years, India has been the largest source of imports for Sri Lanka and it has been the fastest growing. China is in the top-five for imports, but not only was India exporting more than double what China did, but it had the fastest growth.

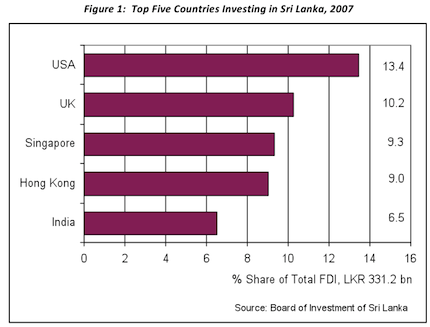

India was not the largest investor in Sri Lanka in 2007, but it has most likely moved up the rankings by now, with investments by the likes of Bharti Airtel.

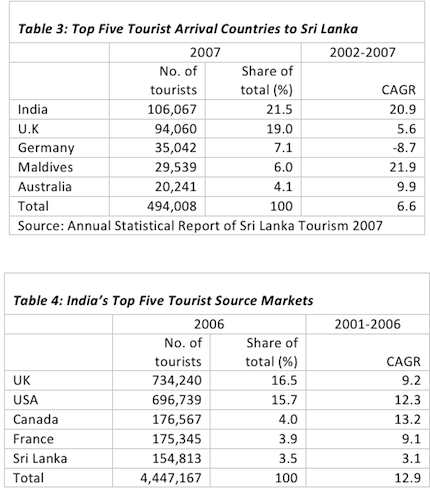

Over the past few years, India has displaced Sri Lanka’s traditional sources of tourist arrivals, helped among other things, by the liberalization of the bilateral air services market in 2003 and visa-on-arrival at the airport for Indian tourists since 2002. India being at the head of the table in terms of tourists to Sri Lanka is unsurprising. What should evoke surprise is that Sri Lanka, a tiny country with less than 1/50th of India’s population, was still one of the top-five source countries for Indian tourism. Despite asymmetrical visa requirements that cause long lines outside consular offices in Colombo and Kandy, Sri Lankans want to come to India. This is evidence of the depth of the relationship.

More evidence can be supplied of the depth and breadth of the India-Sri Lanka relationship. But the above data of the most important socio-economic relations shows that India is well positioned to win the soft-power contests and thereby also to win the hard-power contests with China as a result. It can make Sri Lanka the exemplar of good neighborly relations that it so sorely lacks, other than with miniscule Bhutan and the Maldives.

If the public intellectuals of India start paying attention to what is going on 24 km from the Coromandel Coast and, even better, if they avoid the simple-minded and, with respect, hypocritical analyses like Professor Chellaney, that will be a first step. A democratic country with its own problems of human rights and minority rights can surely empathize with its little brother in the Indian Ocean. Both countries have miles to go in improving their human rights records and managing minority concerns. In the internal debates in Sri Lanka on how to control the LTTE, the methods used to quell the insurgency in Punjab played an important role in the same way that the tactics used against the LTTE are right now most likely being studied in relation to taking back the “liberated zones” of the Maoists in 20 states.

Sri Lanka has historically been a part of the India-centred socio-cultural-economic space. It has also been a meeting place, an entrepot. We took our Buddhism and the seeds of our culture from India in the days of Emperor Ashoka. We took appam and trade unionism from the Malabar coast. Our plantation economy was built by workers who came across the Palk Strait. In contrast, we only have as evidence of our many interactions with China shards of Chinese pottery in the ground and one inscription (in Malayalam!) from the voyages of Admiral Zheng He in the 15th century. All our kings took brides from India; the Chinese took one of our kings and never returned him.

Sri Lanka will not land in China’s lap unless pushed. Professor Chellaney, stop pushing; start pulling.