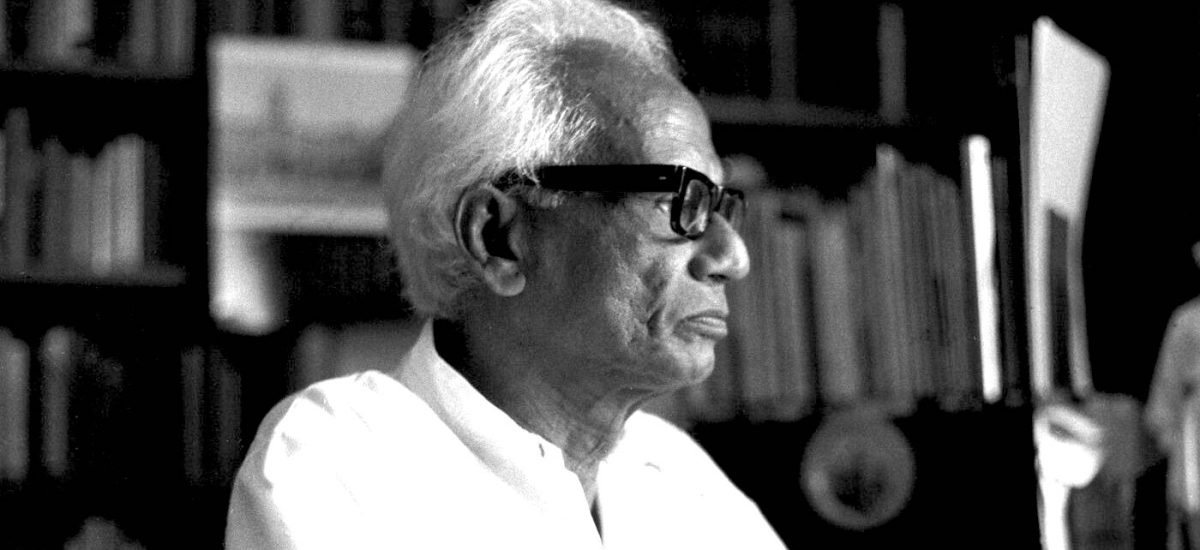

Photo courtesy of Sputnik Media

The Martin Wickramasinghe Collection at the National Library in Colombo contains over 5,000 books. Most of them are worn out and dusty, although well preserved. Some are recent additions. The oldest among the collection date to the early 1910s. Straddling different periods, genres and subjects, they remain a useful guide to the man who owned them, read them and wrote on the topics they covered.

Arguably the most interesting point about them are the annotations. Wickramasinghe was a voracious reader, “omnivorous” as he called himself and he spent much of his income on books. He was indiscriminate yet critical in what he read. This comes out quite well in the annotations. Some of the older books have notes every few pages. The more recent ones hardly have them at all. This shows that Wickramasinghe was learning about these subjects for the first time through these texts and that he was reading as much as he could about them. As he read, he remembered. As he remembered, he annotated.

Most of these annotations are marginal comments. Some point to other sources. Many are critical, hardly any laudatory. On the side of one page in the 1934 edition of Caroline Rhys Davids’s Outline of Buddhism, to give one example, he argues the author seems “ignorant of modern anthropology.” In his copy of Maurice Baring’s An Outline of Russian Literature, published in 1914, he critiques the author’s characterisation of Leo Tolstoy. Responding to Baring’s comment that “Tolstoy wrote about himself from the beginning of his career to the end”, Wickramasinghe writes, “This observation is wrong”, adding that “it is… altruism which impels Tolstoy to confess all the wrongs he has committed.”

Between Baring’s book and Rhys Davids’s there is a space of 20 years. During this period Wickramasinghe had matured and evolved. Beginning his life in Colombo as a bookkeeper to a shop owner, he went on to write articles to the Dinamina. In 1914 Wickramasinghe wrote his first novel, Leela. His preface to the first edition makes it clear how much of an influence the books he was reading had upon him. In no ambivalent terms, he notes the futility of drawing lines between Western and Eastern philosophy, science, between ways of looking at the world. The story itself unremittingly critiques tradition and order.

Such attitudes could only have been fostered through the books he was devouring. As he himself recounts in Upan Da Sita, he started reading rationalist and Western texts almost as soon as he shifted to Colombo in 1906.

Wickramasinghe’s granddaughter Ishani remembers his library all too well. “As a teenager I read D.H. Lawrence, Tolstoy, the Russians, from his collection,” she says. “For him, reading was a window to the world.” She recalls he was insistent that his children and grandchildren read English and that they did not limit themselves to Sinhala literature. “He regarded Sinhala literature highly,” she notes. “And he had a complicated relationship with Western culture. He critiqued it, yes, but he also recognised its value.”

The leading litterateur of his day, Wickramasinghe was one of the leading Sri Lankan, South Asian and Asian cultural figures of his time. As Sarath Amunugama reminded me not long ago, he was a contemporary of not only Piyadasa Sirisena and W.A. Silva, but also Ananda Coomaraswamy and Cumaratunga Munidasa. Yet despite having passed away almost 50 years ago, Wickramasinghe’s life, work and thought have yet to be studied fully by scholars. May 29, marked his 135th birth anniversary.

In her study of Geoffrey Bawa, the historian Shanti Jayewardene notes that we have still not understood the intellectual modernists of South Asia. She includes in this pantheon not just Coomaraswamy and Cumaratunga Munidasa but also George Keyt, Lionel Wendt, Chitrasena, Lester James Peries, Ediriweera Sarachchandra and Ian Goonetilleke. Writing of Coomaraswamy, she notes that they all remain “poorly understood.”

Jayewardene also includes Martin Wickramasinghe. She refers to Anupama Mohan’s point that he “projected on to the rural, the possibility of recovering a subjectivity unsullied by colonial inequities.” Mohan’s book, Utopia and the Village in South Asia, dissects his writings on Sinhala rural culture and his supposed idealisation of it.

Whether Wickramasinghe’s framing of the culture he came from was as romantic as Mohan makes it out is debatable. Yet those writings, influenced as they were by the books he read at an early period, represent a rupture in the intellectual trajectory of colonial Sri Lanka. This is why it is difficult to place Wickramasinghe in the same league as Keyt, Wendt and the 43 Group. The latter had to study the culture they were born to. Wickramasinghe, on the other hand, was a product of that culture. He did not have to study it to write on it.

The biggest challenge for scholars of Wickramasinghe and of cultural modernism in 20th century Sri Lanka is a lack of familiarity with his source texts, particularly those written in Sinhala. While Keyt, Wendt and Peries have been studied exhaustively and examined from various perspectives, Wickramasinghe remains limited to a Sinhala speaking audience and a Sri Lankan scholarship. This is a regrettable omission given the many contributions he made not merely to “Sinhala” culture but also to our understanding of that culture and the ways of life and of seeing, which underpinned it. His novels, in particular those he wrote after 1944, have enjoyed a much greater reputation because they became prescribed texts at schools and universities even during his lifetime. As the political researcher Harindra Dassanayake puts it, “When you ask the question, ‘How did you first come across Wickramasinghe?’, you always get the same response: Madol Doowa.”

Perhaps such a reading is reductive. Seminal although his fiction was, it must be remembered that Wickramasinghe wrote 13 novels and some short stories in addition to a few plays and two books of poetry. Although he forayed into journalism some years after his first novel was published, he made use of the space he got to write as much as he could on anything and everything he had read until then. This was a formative time in Sri Lanka’s modern history when radical politics had reared its head and calls were made for self-government, when universal suffrage was about to be granted and the colonial order was rupturing from within. Wickramasinghe’s intervention at this point, massive as it is, can be gleaned from the articles he was writing and getting published in the press.

In this regard, he made two seminal contributions. He began writing articles in the Dinamina in 1916 and almost immediately wrote on science, evolution, philosophy and anthropology. In Upan Da Sita Wickramasinghe recounts attending debates, reading periodicals and subscribing to foreign magazines, all of which helped transmit Western radical ideas to a deeply colonised society. In writing on these topics, in a mode and form accessible to a Sinhala speaking audience, he went beyond other cultural figures who lacked such contact with mass audiences. These articles, authored under the penname Hethuvadiya or “Rationalist”, gained enough attention and controversy to convince D.R. Wijewardene to hire him at Dinamina in 1920. Twelve years later he was promoted as editor.

Not long afterwards he also began writing in English. In English he wrote mostly on Sinhala culture, Buddhism and other aspects of Sri Lankan society and history. This intervention has yet to be appreciated in full. Before Wickramasinghe very few Sri Lankans wrote so much on Sri Lankan culture and history. As Senake Bandaranayake has reminded us of Ananda Coomaraswamy such intellectuals, drawn as they were from the very colonial societies they critiqued, projected a view of the country which tended to be anachronistic and romanticised. Wickramasinghe went beyond these frameworks and, as Amunugama observes, explored the underpinnings of Sinhala society. in this he did not have to discover or rediscover his society as Keyt did through literature and poetry and Wendt through photography. By the time he came of age he had immersed himself in Sinhala and Buddhist literature well enough to write on them for foreign audiences.

Taken together, these contributions make up two sides of the same coin. He was an outsider looking in and an insider looking out. As Nalaka Gunawardena puts it, he was also the public intellectual of his time, “a powerful shaper of public discourse” who made it clear, perhaps for the first time in Sri Lanka, that “one cannot become a public intellectual without reaching the public.” It goes without saying that such a contribution would not have been possible without the many books he read indiscriminately, yet critically and the familiarity he was able to acquire with both local and Western texts.

These interventions also required much humility, a quality Wickramasinghe never lacked in his writings. Underlined in his copy of Anatole France’s On Life and Letters: Second Series, published in 1922 and perhaps bought during that time, is an aphorism that could not have better summed his way of looking at the world: “One seems to be almost attractive as soon as one is absolutely true.” In being true to himself, Wickramasinghe carved his own path. Nalaka Gunawardena puts it well: “Rarely has he been surpassed in this country, in his time or since.” It is this that has yet to become the subject of a definitive study.