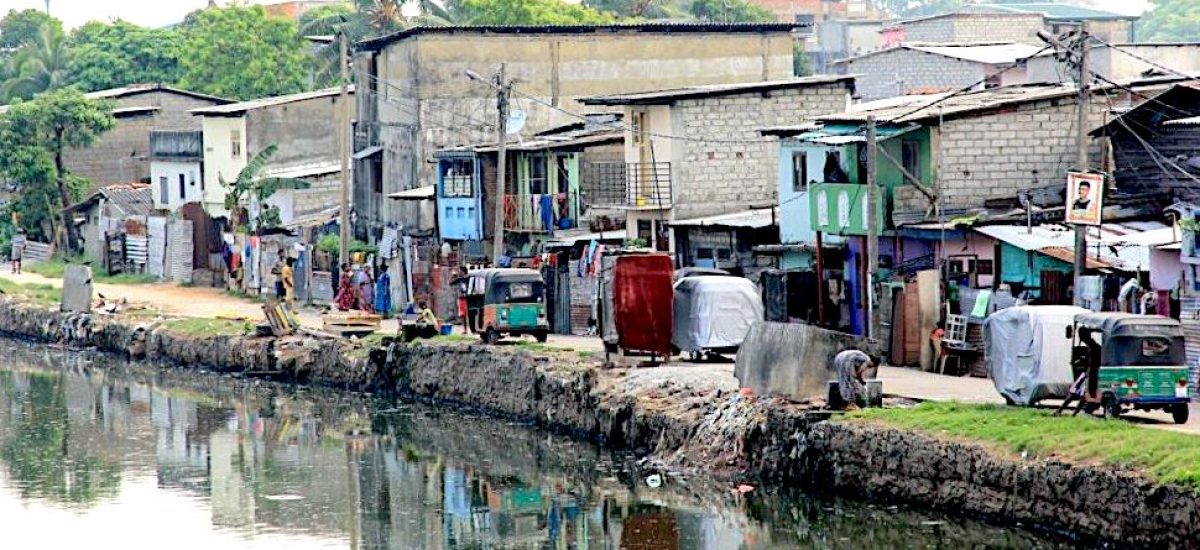

Photo courtesy of UN Habitat

In the throes of a historic economic crisis, Sri Lanka is confronting a less visible but equally devastating public emergency – the widespread failure of urban sanitation infrastructure. A study released by the Marga Institute has brought this issue to the fore, revealing the staggering financial, health and social costs of underinvestment in drainage, wastewater and sanitation systems.

Spanning all 25 districts and surveying 1,329 households, the study is the first of its kind to map the economic dimensions of urban sanitation in such detail. The findings are unambiguous: the collapse of urban sanitation is compounding public health challenges, undercutting economic recovery and disproportionately affecting already vulnerable communities.

Unplanned urban sprawl, ageing infrastructure and erratic waste management protocols have created conditions ripe for disaster. In cities and towns alike, residents face frequent flooding, stagnant water and open canals that serve as breeding grounds for waterborne diseases.

“Thousands of urban families are trapped in a vicious cycle of preventable illness, medical expenses and lost income,” explains Lashinika of the Marga Institute. “For many, water, sanitation and hygiene, collectively known as WASH, are no longer development goals but immediate matters of survival.”

The costs are considerable. Households reported annual medical expenses ranging from Rs.2,500 to Rs.50,000 due to sanitation related illnesses. While wealthier urbanites may absorb these costs, for daily wage laborers and micro-entrepreneurs, who make up over 50% of the study’s respondents, these are debilitating.

Absenteeism is another economic dimension often overlooked. Kalutara, one of the worst affected districts, reported an average of 14 days lost per household per year to illness or water related disruptions. The numbers stood at 11 in Gampaha, and five in both Colombo and Matara. For families on the brink of financial precarity, these lost workdays translate directly into lost meals.

A particularly alarming facet of the study is the disparity in water quality across districts. While districts such as Kandy and Matara benefit from relatively clean sources others, particularly in the North and East, as well as in Puttalam and Matale, face dangerous levels of contamination. Fecal matter, chemical pollutants and unfiltered runoff are routinely detected in domestic water supplies, presenting serious health risks including chronic gastrointestinal illnesses and organ damage.

This contamination doesn’t only manifest in physical ailments. The psychological toll, especially on women, is immense. In many regions with intermittent or unreliable water access, women are forced to travel long distances daily to collect clean water. This unpaid, invisible labor extracts a cost in terms of time, energy and mental strain and limits women’s participation in income generating or educational activities.

Inadequate drainage compounds the crisis. Cities such as Matale, Galle and Kandy, ironically among the country’s most urbanized, suffer from systemic drainage failures. Clogged drains, garbage choked waterways and the absence of sustainable flood mitigation strategies make these cities highly vulnerable, especially during the monsoons.

In contrast, districts such as Polonnaruwa and Kilinochchi, with either lower population densities or relatively better planning, face fewer drainage related disruptions. This dichotomy signals an urgent need for place-based planning and localized policy responses rather than broad, one size fits all national schemes.

The causes of these dysfunctions are not merely technical. Corruption, weak oversight and a lack of public engagement exacerbate infrastructural decay. In many municipalities garbage collection is irregular, uncoordinated and, in some cases, entirely absent. The Marga Institute highlights the critical role of governance reform in any meaningful sanitation revival.

The burden of this crisis, while shared, is not borne equally. Women and children are disproportionately affected not just in terms of health but also opportunity. When school attendance is interrupted due to illness or infrastructural damage, it interrupts the trajectory of education. In communities surveyed, it is not uncommon for children to miss multiple weeks of schooling during peak rainy seasons due to impassable roads or flooding.

Women, often primary caregivers, bear the brunt of caring for the ill, fetching water and managing household hygiene without adequate infrastructure. As such, the crisis reinforces cycles of gender inequality and poverty.

Quantifying the crisis

The study’s statistical findings underscore the economic drain caused by poor sanitation. Employment status of affected households: 34% are micro-entrepreneurs (including small shopkeepers and food vendors), 33% are unemployed and 20% rely on casual labor (tea plucking, tailoring, masonry).

Average annual medical costs by district: Gampaha Rs.15,000, Kalutara Rs.14,712, Hambantota Rs.13,846 and Batticaloa, Mullaitivu and Ratnapura Rs.2,500.

Such disparities not only illustrate unequal burdens but also suggest targeted policy interventions could yield high impact results in specific hotspots.

Towards a sanitation revolution

The Marga Institute’s report concludes with an actionable roadmap:

- Governance reforms: Strengthening local accountability and ensuring transparency in sanitation funding.

- Infrastructure investment: Directing resources toward high risk zones identified in the study.

- Community-based approaches: Mobilizing local waste disposal collectives and hygiene awareness campaigns.

- Monitoring and evaluation: Establishing metrics to assess the performance and adaptability of sanitation interventions.

- Climate resilience: Integrating flood resistant planning in urban sanitation designs.

This approach underscores the need for intersectional policy that spans health, environment, urban planning and social justice.

Sri Lanka is at a critical juncture. As the country attempts to stabilize its economy, it cannot afford to ignore the bedrock upon which its social and economic wellbeing rests. Sanitation is not merely a technical issue; it is a human right, a public health imperative and an economic necessity.

Failure to act decisively risks not only deepening existing inequalities but also undermining national development goals. A comprehensive and inclusive sanitation strategy is no longer optional, it is essential.