Blue-green land and waterscapes act as ecological corridors across land and water in creating an ecological continuity in order to protect and restore the habitats of native and naturalized species. In addition, these ecological corridors also help to conserve and improve the habitats of migratory species as well. One of the main objectives of establishing blue-green land-waterscapes is to reconcile increasing local/regional development and human livelihood challenges in a sustainable manner while at the same time safeguarding biodiversity and their habitats/ecosystems as far as possible.

While green landscapes are natural and semi-natural terrestrial vegetation types like natural forests and grasslands, blue waterscapes are aquatic or semi-aquatic vegetation types such as seagrass meadows, mangroves and coastal and other wetlands. These vegetated coastal ecosystems known as blue carbon ecosystems are some of the most productive on earth and located at the interfaces among terrestrial, freshwater and marine environments. They provide us with essential ecosystem services such as serving as a buffer in coastal protection from storms and erosion, spawning grounds for fish, filtering pollutants and contaminants from coastal waters thus improving coastal water quality and contributing to all important food security.

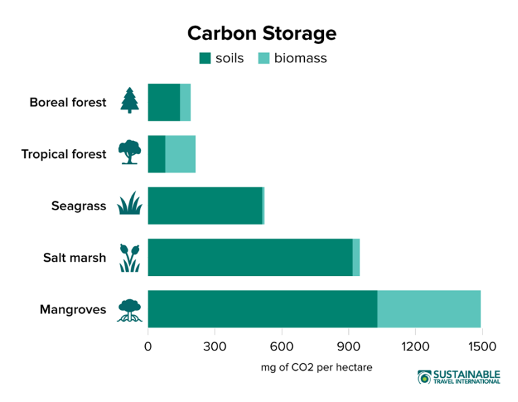

In addition, they capture and store blue carbon from the atmosphere and oceans at significantly high rates per unit area than tropical forests (Figure 1) and hence act as effective carbon sinks. By storing carbon, these ecosystems help to reduce the amount of greenhouse gas in the atmosphere, thus contributing significantly to mitigate the effects of climate change.

Figure 1: Carbon storage in different vegetation types (Source: What Is Blue Carbon and Why Does It Matter? Sustainable Travel International)

Blue-green carbon markets

The recognition of blue carbon ecosystems (primarily mangroves, seagrasses and tidal marshes) as an effective natural climate solution paved the way for their inclusion within carbon markets. Blue carbon is the marine analog of green carbon, which refers to carbon captured by terrestrial (i.e., land based) plants. The blue-green carbon market involves buying and selling carbon credits from projects that protect and restore coastal and marine ecosystems (blue carbon) and terrestrial ecosystems (green carbon). Since blue carbon ecosystems have higher carbon sequestration (capture and store) potential compared to their terrestrial counterparts, blue carbon credits are worth over two times more than green carbon credits. They offer opportunities for commercial enterprises to offset carbon emissions and in turn support climate action.

Blue carbon projects are expected to grow twofold in the near future. With the recent surge in international partnerships and funding, there is immense growth potential for the blue carbon market. However, it is critically important to look beyond the value of the carbon sequestered to ensure the rights and needs of local communities that are central to any attempt to mitigate climate change using a blue and green carbon project.

Blue carbon projects can serve as grassroot hubs for sustainable development by developing nature based solutions in these ecosystems thus contributing to both climate change mitigation and adaptation. Globally, numerous policies, coastal management strategies and tools designed for conserving and restoring coastal ecosystems have been developed and implemented. Policies and finance mechanisms being developed for climate change mitigation may offer an additional route for effective coastal management. The International Blue Carbon Initiative, for example, is a coordinated, global program focused on conserving and restoring coastal ecosystems for the climate, biodiversity and human wellbeing.

Until recently, most of these opportunities focus on carbon found in the above ground vegetative biomass and do not account for the carbon in the soil. On the other hand blue carbon, in particular, has the potential for immense growth in carbon capture economics in the near future and can provide significant socioeconomic and environmental benefits. Consequently, blue-green carbon habitats in the Gulf of Mannar-Palk Bay region represent invaluable assets in climate change mitigation and coastal ecosystem conservation and sustainable development.

Gulf of Mannar and Palk Bay trans-boundary region

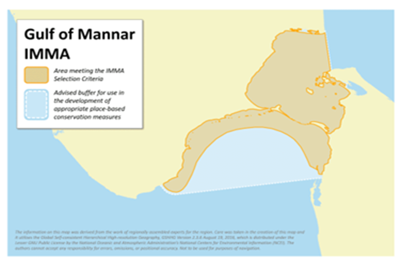

The Gulf of Mannar and Palk Bay region form a transboundary area within the waters of southeastern India and northwestern Sri Lanka. This region supports dense seagrass meadows having a high level of marine biodiversity including marine mammals such as dugong. Sea turtles are frequent visitors to the gulf while sharks, dolphins, sperm and baleen whales too, have been reported from this area. The Mannar region is recognized as an Important Marine Mammal Area (IMMA) of the world by IUCN (Figure 2) and also an Important Bird Area by Birdlife International. This region as a whole is a store house of unique biological wealth of global significance and as such is considered as one of the world’s richest regions from a marine biodiversity perspective.

Figure 2. Gulf of Mannar and Palk Bay IMMA (Source: IUCN Joint SSC/WCPA Marine Mammal Protected Areas Task Force, 2022 IUCN-MMPATF (2022))

Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve – India

India has already declared a part of this region as the UNESCO Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve covering an area of 10,500 km2 of ocean with 21 islands and the adjoining coastline. The islets and coastal buffer zone include beaches, estuaries, and tropical dry broadleaf forests while the surrounding seascape of the Marine National Park (established in 1986) and a 10 km strip of the coastal landscape that include seaweed communities, sea grass communities, coral reefs, salt marshes and mangrove forests form the coastal and marine component of the biosphere reserve on the Indian side of the Gulf of Mannar.

Figure 3: Gulf of Mannar and Palk Straits (Source: Drishti IAS & Google Images)

Sri Lankan proposed biosphere reserve

On the Sri Lankan side of the Palk Bay there is a semi-enclosed shallow water body between the southeast coast of India and Sri Lanka with a water depth maximum of 13 m. To the south, a chain of low islands and reefs known as Adam’s Bridge or Rama Setu separates Palk Bay from the Gulf of Mannar. The Palk Bay leads to Palk Strait (Figure 3). Palk Bay is one of the major sinks for sediments along with the Gulf of Mannar. Sediments discharged by rivers and transported by the surf currents as littoral drift settle in this sink.

On the Sri Lankan side of the Palk Bay, studies are being conducted by the Dugong and Seagrass Conservation Project to establish an additional 10,000 hectares of Marine Protected Area to support the conservation of dugongs and their seagrass habitat in the Gulf of Mannar and Palk Bay. This project will involve the preparation of a multiple community based management plan in conjunction with government, fishing communities and the tourism industry.

With this valuable information emerging from projects of this nature, Sri Lanka has real opportunities to create a large marine protected area in the Gulf of Mannar and Palk Bay region and eventually merging them together with the Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve of India to form a trans-boundary biosphere Reserve.

Terrestrial and Marine Spatial Plan for the Gulf of Mannar and Palk Bay Region

Therefore, an excellent opportunity awaits both the governments of Sri Lanka and India to collaborate in preparing of a terrestrial and marine spatial plan for this region, a prerequisite before going further on designing and implementing large scale development plans in establishing wind energy farms, mineral sand extraction, fishing industry, oil exploration and tourism development. Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning (CMSP) is an integrated, place based approach for allocating coastal and marine resources and space while protecting the ecosystems that provide these vital resources.

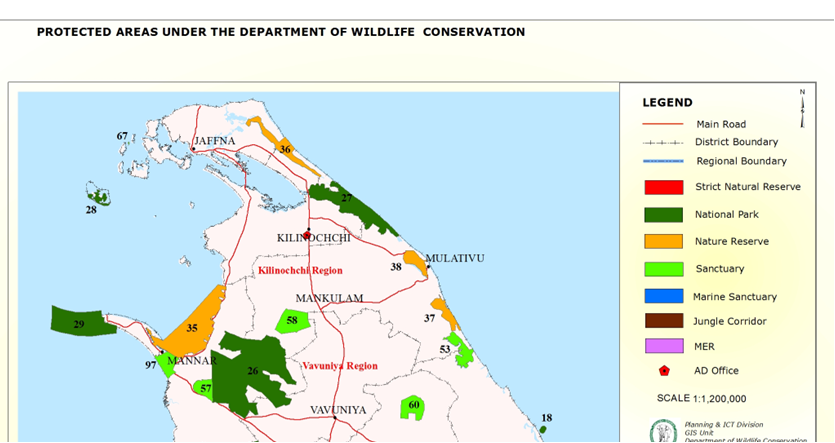

On the Indian side, the Gulf of Mannar Biosphere reserve is well established and functional. On the Sri Lankan side, already there are three DWLC managed protected areas i) Adam’s Bridge Marine National Park (# 29 in the map – 18,990 ha declared in 2015), ii) Vedithalathiv Nature Reserve (# 35 -29,180 ha declared in 2016) and iii) Vankalai Sanctuary ( # 97 -4839 ha declared in 2008) (Figure 4) which can serve as the core zone of the Sri Lankan counterpart of a trans-boundary biosphere reserve. Due to the integrated nature of shallow wetland and terrestrial coastal habitats Vankalai Sanctuary, in particular is highly productive, supporting high ecosystem and species diversity. This site provides excellent feeding and living habitats for a large number of water bird species including annual migrants, which also use this area on arrival and during their exit from Sri Lanka.

Figure 4: Protected Areas in Northern Sri Lanka Managed by the Department of Wildlife Conservation (Source: DWLC)

Having several coastal and marine protected areas already within the Sri Lankan territory provide an excellent opportunity to establish the Gulf of Mannar-Palk Bay Blue-green Biosphere Reserve (Sri Lanka) initially and eventually to join up seamlessly with the already established Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve on the Indian side to create a trans-boundary blue-green biosphere reserve.

This makes perfect sense because unlike sedentary plant species, mobile animal and plant groups (phytoplankton, in particular) do not respect human demarcated territorial boundaries. The provision of a common and unhindered protected coastal and marine passage for their customary movement for food and raising young is therefore of crucial importance in conservation management. Scientific evidence based selection of additional areas, if necessary and their respective boundaries are best be determined in consultation with expert groups on marine mammals and reptiles, birds, fish, coastal vegetation conservation, sociology and industrial development from both sides of the divide.

Proper spatial planning needs to be done before large scale development plans are designed and implemented in order to avoid conflicts of interest leading to inordinate delays and teething problems in project initiation. As a priority, the protected blue-green core and buffer regions need to be demarcated for their conservation. This could best be done in this narrow passage of land and water between Sri Lanka and India (Palk Strait and Gulf of Mannar) by preparing a marine and terrestrial spatial plan along the UNESCO Man and Biosphere conceptual guidelines differentiating core, buffer and transition zones. While the protected areas in the core and buffer zone provide all important ecosystem services that would also serve as breeding ground for fish, crustaceans, marine reptiles, birds and mammals thereby provisioning sustainable industries to be developed in the surrounding transition areas demarcated in the joint spatial plan.

In addition, the Satoyama Global Initiative established by the Japanese at UNESCO as a global effort in 2009 to realize societies in harmony with nature in which specifically referring to the management of socio-ecological production landscapes in marine and coastal regions, is also a good model to be considered for conservation of biodiversity and co-existence between humans and nature.

Final Plea

If this proposal to establish a Trans-boundary Blue-Green Biosphere Reserve in the Gulf of Mannar and Palk Bay is acceptable in principle to the governments of Sri Lanka and India, it would be ideal if the Man and the Biosphere (MAB) program UNESCO, which is an intergovernmental scientific program whose mission, is to establish a scientific basis for enhancing the relationship between people and their environments to partner with the relevant government and non-governmental agencies in both countries in making it a reality. This proposed concept has all the necessary elements for developing a unique sustainable conservation and industrial development strategy via nature based solutions while at the same time contributing to both climate change mitigation and adaptation.