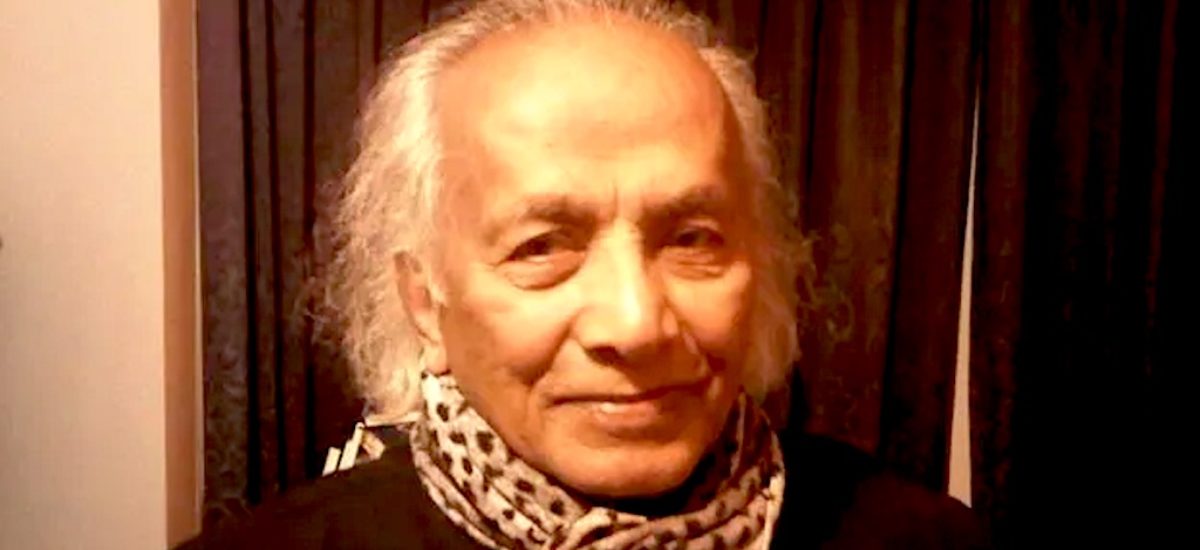

Born in Kataluwa, Galle District, Comrade Prins Gunasekera was first elected as the Member of Parliament for Habaraduwa electorate in March 1960 and re-elected under the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) ticket in 1970. However, due to conflicts with the leaders of the ruling coalition government over the Criminal Justice Commission Act and the trials to be conducted under it, he became an independent.

Looking at Comrade Prins’s ideological evolution, starting from the old left politics of the 1950s, he changed in the 1970s to a position of being sympathetic towards the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP). He continually stood up for human rights and democracy. He was a key figure in the political landscape as well as in the legal history of Sri Lanka.

From 1971 onwards, Comrade Prins was deeply involved in civil rights movements. Collaborating with other human rights activists such as Comrade Bala Tampoe and Lord Avebury representing Amnesty International, he investigated the state repression that had been launched across Sri Lanka. In 1972, during the main trial of the Criminal Justice Commission, the government charged 41 individuals with conspiring to overthrow the Queen’s state. Comrade Prins and other legal teams challenged the legitimacy of the commission and protested. As a result, they were barred from appearing before the commission. This act of moral courage underscores his commitment to justice.

He continuously advocated for the right of the JVP to engage in democratic politics. His ancestral home in Kataluwa had been allowed to be used for our political activities. His home in Rosmead Place was the headquarters of the 1982 presidential election campaign. Comrade Prins also filed a petition against the infamous Lamp-Pot referendum, which destroyed the entire democratic process and extended the term of parliament by six years.

His work alongside a new generation of human rights lawyers highlighted the issue of state violence and repression. I would like to mention at this moment, Comrade Prins’s younger sister’s son Kanchana Abeypala, as well as comrades like Charitha Lanka Pura and Wijeyadasa Liyanarachchi. They advocated for the interests of those who were at the receiving end of state violence in the eighties. The regime’s terror campaign worsened. By 1989, more than 15 lawyers had been assassinated. On this occasion, I consider it our duty to remember and pay our respects to them.

In the late 1980s, the intimidation from state forces made Comrade Prins and his family to leave Sri Lanka. Despite being in exile, he continued to work for the protection of human rights.

His book A Lost Generation: Sri Lanka in Crisis: The Untold Story” is a chronicle about the dark era in Sri Lanka. It provides a searing account what happened from 1977 to 1990. He has named the presidents of that time as serial killers, who were driven by an unbridled greed for total power. This book provides much insight into the political trajectory of Sri Lanka, which was marked by the fraudulent 1982 referendum, the brutalities of 1988-89 and the state repression of that time.

The 1983 Black July massacre, orchestrated by the United National Party, marked a critical and decisive turning point in the island’s history. The state sanctioned violence against Tamils was used as a pretext to proscribe the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), the Nava Sama Samaja Party (NSSP) and the Communist Party of Sri Lanka. After this pogrom, the LTTE became extremely strengthened.

The state while suppressing the JVP, and unleashing terror across the country, continued to maintain the ban imposed against it. It was those actions of the state that ultimately led to armed violence in the South. In parallel, the Tamil community was also terrorized. This further strengthened the violent movement in the North and East. Comrade Prins’s book sheds light on the state-sponsored death squads used in the South for this suppression, like PRRA, Black Cats, Yellow Cats, and others, which operated with impunity under indemnity laws.

We know that Comrade Rohana went underground as soon as the pogrom began. Politically, I did not agree with his decision. Because it would have allowed the government to make the people believe the state’s version of events that the JVP was behind the Black July Pogrom.

Comrade Prins would have realized that the desired political objectives could not be achieved by remaining underground. Fearing that the image created by the government would become valid, he would have tried to persuade Comrade Rohana to bring the party to the open, above ground. Accordingly, in the mid-eighties, Comrade Prins had met Comrade Rohana in Bulathsinhala and discussed the matter a whole night.

Subsequent events show that Comrade Rohana did not accept Comrade Prins’s reasoning. Comrade Rohana had informed Comrade Prins that the party leadership had already decided on an alternative plan of action. Comrade Prins’s disappointment at that time is understandable. However, his efforts reflect his desire for a peaceful resolution of the situation that prevailed.

Comrade Prins’s work extended from legal representation to challenging the state’s abuses of power. For example, he represented the JVP in the case against the fraudulent referendum and exposed the corruption and violence carried out during that referendum.

Comrade Prins had a blend of progressive left ideals and Sinhala nationalism. Nevertheless, his fearless commitment to justice earned him widespread respect.

The centenary of his birth and the relaunch of his book has given us an opportunity to reflect on an era when young Sri Lankans were sacrificed to protect the political and economic interests of a privileged few. Instead of the state-sponsored or state-sanctioned narratives about the 1987-89 uprising, Comrade Prins’s work offers a critical account of those brutal realities.

As we mark his birth centenary, his legacy should be honored by committing ourselves to a world that safeguards human rights and democracy. His life reminds us again and again of the importance of remaining courageous and safeguarding humanity.

The wealth of political and legal experience Comrade Prins Gunasekera possessed would have been of immense use for the current government, which is attempting to create a more democratic and accountable state.

If the JVP had listened to people like Comrade Prins rather than to other voices, and decided to enter open politics earlier, it would have been possible to save the tens of thousands of lives, including those of the leaders. The massive loss of life and destruction, and the terror that ensued, could have been prevented. Under those historical circumstances, the JVP could have achieved a competitive political advantage by exposing the fraudulent and violent role played by the UNP regime led by Mr J R Jayewardene. Nonetheless, all of that has now become a tragic history. Yet, there are many valuable lessons that could be and should be self-critically learned from this.