Photo courtesy of Time

In Israel/Palestine these are dark, terrible times with no obvious end in sight to the mounting bloodshed and destruction. It is also a time that gives rise to difficult but necessary conversations: no more so than between friends, as is the case with myself and Ruwanthie de Chickera. Ruwanthie’s recent Groundviews piece is a passionately argued – and doubtless, no less passionately felt – condemnation of the intense violence currently being visited on Gaza, and by inevitable extension its population, by the Israeli Defence Forces (IDF).

While there is plenty to agree with in her argument, it also raises some important difficulties. First in the depiction of Israel, as both stated and implied. Over the last few weeks, in Sri Lanka as elsewhere many of us have watched innumerable interviews with Middle Eastern experts of differing kinds. But how many critical, dissenting voices from inside Israel have featured in popular Sri Lankan viewing, I wonder?

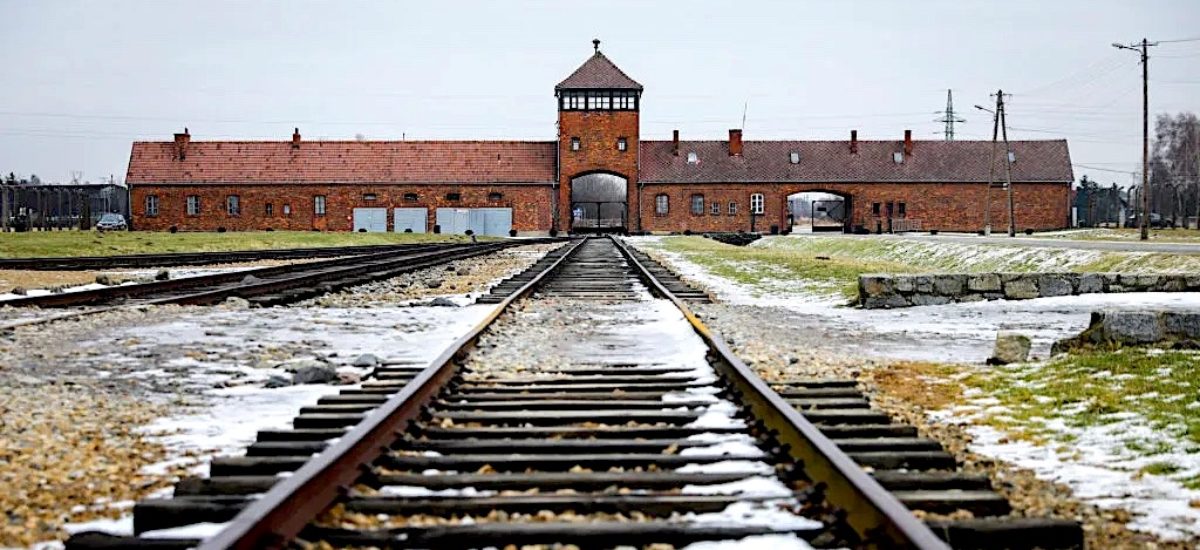

Take, for example, the voice of liberal Israeli intellectual and author Yuval Noah Harari. Asked about Israelis reaction to Hamas’s devastating slaughter of over 1,000 Israeli civilians, Harari responded as follows: “It goes back to the deepest fears and darkest moments of Jewish history. First people compared it to the (1973) Yom Kippur War. But very quickly the narrative changed, and now everyone is comparing it to scenes from the Holocaust, Einzatzgruppen[1], pogroms. For a couple of hours the state of Israel disappeared.”

This is the kind of vital voice and perspective, and with a sense of understanding of the story underlying this voice, that is missing in Ruwanthie’s account. If she elects to describe events in Israel/Palestine as a “single story”, fine. Just as long as the story encompasses multiple narratives, in particular those of all the key characters. Likewise I am all for, as she suggests, “Taking a stand against occupation, against apartheid …. against genocide”. But again, just so long as all those on the receiving end of horrendous abuses are included in the accompanying narrative. From the tenor of Ruwanthie’s argument, I suspect many Israelis would consider themselves absent from the account, except as, by default, witting or unwitting supporters of the ongoing violence in Gaza.

This in turn is why the depiction of the “single story” as “horrifyingly simple” remains problematic. For Ruwanthie, the time has passed for approaches based on an appreciation of “multiple conflicting angles, that need to be pondered on, deliberated or discussed, that require bilateral compromise or mediation . . . still at that crossroad where thoughtful, mature negotiation could lead us away from the precipice.”

But what exactly is the alternative proposed here? Expressions of solidarity with the people are Gaza are important and necessary but where do they get us in terms of moving towards what I and many others would see as the negotiations (thoughtful, mature or otherwise) urgently required in order to try and walk the wider region and perhaps beyond back from the abyss? Not very far is, sadly, the answer. Political thinking based on full cognizance of the interests and positions of both sides, Israeli and Palestinian, is an unavoidable precondition for de-escalation, a ceasefire and ultimately, stable peace. And in that context, binary/good vs. evil type approaches favouring either side are part of the problem, not the solution. Ruwanthie suggests that since October 7, the key issues involved have somehow ceased to be complex, replaced, presumably, by the “single story” narrative she favours.

The continued importance of seeing things from both sides of the conflict, however, is well illustrated in UK Guardian columnist Jonathan Freedland’s recent assertion with respect to calls for an unconditional ceasefire, which as he rightly notes, “naturally resonate with anyone who grieves for those under the nightly bombardment that has already killed so many Gazans. It seems such a simple, obvious remedy. Until you stop to wonder how exactly, if it is not defeated, Hamas is to be prevented from regrouping and preparing for yet another attack on the teenagers, festivalgoers and kibbutz families of southern Israel.”

If nothing else, Freedland’s commentary underscores the continued presence of complexity, nuance in the ground picture. Giving voice to Israeli, and indeed wider Jewish, anxieties, he goes on to note that “the chant demanding that Palestine be free ‘from the river to the sea’ sends shivers down Jewish spines. Because that slogan does not demand a mere Israeli withdrawal from the occupied West Bank. What most Jews hear is a demand that Israel disappear altogether. And that Israeli Jews either take their chances living in a future Palestine under the likes of Hamas – or get out. But where to?”

Ruwanthie argues that “while it is impossible to condone what Hamas did, it is possible to understand why they did it”. Bur surely viewed from an Israeli perspective, precisely the same argument holds for the murderous IDF response to the Hamas attacks? A conundrum that returns us, inevitably, to complexity.

Changing tack slightly, in the Sri Lankan content it is important to note that official attitudes to Israel/Palestine have changed significantly over time. Mahinda Rajapaksa’s recent visit to the Palestinian Embassy in Colombo underscored his long standing personal association with the Palestinian cause. After establishing diplomatic relations with the Israel in 1956, Mrs. Sirimavo Bandaranaike proceeded to cut them off in 1970. In my current research of a new book on Sri Lankan history I am looking at the 1980s.

Sri Lankan newspapers of the time were replete with stories about the Israeli Special Interests Section established at the US Embassy in 1984, Israeli arms sales to the Jayewardene government and specialist military training provided by the Israeli official security agency Shin Bet (among others). The arms sales continued well into the Rajapaksa era, which leads me to wonder if the current escalation of conflict in Gaza had occurred in the mid-1980s, would there have been as many out on the streets protesting for a “Palestine free from the river to the sea” or at least among Sinhalese might the boot have been on the other foot?

I shall conclude with another quotation from Jonathan Freedland that well captures what I believe to be a viewpoint shared by many liberal and anti-Zionist Jews and equally, in slightly different words, by a portion of the Palestinian and wider Arab intelligentsia. I do so because, again, I suspect it is a view and voice that often fails to get sufficient coverage and recognition in Sri Lanka.

“This is where you wind up,” he suggests, “when you view this conflict in monochrome, as a clash of right v wrong. Because the late Israeli novelist and peace activist Amos Oz was never wiser than when he described the Israel/Palestine conflict as something infinitely more tragic: a clash of right v right. Two peoples with deep wounds, howling with grief, fated to share the same small piece of land.

So, this is not a football game. It has no need for spectators who root for one team against the other, goading their chosen side to go to ever further extremes. This is not a game, for one grimly obvious reason. There are no winners – only never-ending loss.”

Amen to that.

[1] Paramilitary Nazi death squads responsible for mass murder, particularly of Jews, during World War II, in Nazi occupied Europe.