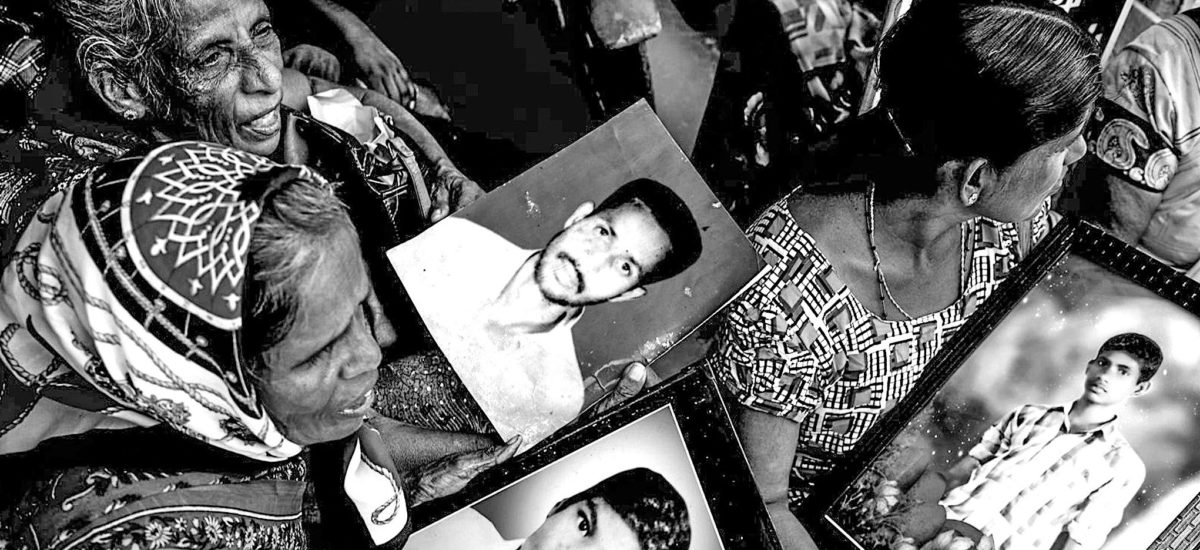

Photo courtesy of Kumanan Kanapathippillai

Are you a wife or a widow if your husband has been gone for years? Are you still a mother if your only child is missing? Do you speak of your brother whom you have not seen in decades? A wife keeps the light on each night hoping her husband will come home. A mother cooks extra food for each meal in case she has another mouth to feed. A daughter’s face lights up hopefully at each knock on the door.

The uncertainty about the fate of missing relative results in a state of perpetual suffering, a state of frozen grief. Life is put on hold. Other family members are neglected; they do not understand and this results in social isolation. The loss is not considered real without a body. There is an obsession with finding out what happened. Without a death certificate it is not possible to access bank accounts, sell land or get a child’s passport.

This state of limbo has a name. It is called ambiguous loss; the heartache, rage and hopelessness felt by relatives of the disappeared, some of whom for many decades have been living with the eternally unanswered question – is the loved one dead or alive?

Ambiguous loss is a psychological condition experienced by families of missing persons who live in a state of uncertainty because they do not know what has happened to their relatives. Ambiguous loss is the most stressful type of loss because there is no proof to bring about closure – a story with no ending where they cannot mourn, honour the lost person or have funeral rites.

Families feel their lives have lost meaning. They have lost their place in society. They are helpless and assign blame. They are looking for an answer. They have lost control over their lives. They have lost their sense of identity in relation to the missing person. They have mixed feelings and feel guilty that they may want the person dead to know for sure. They do not know how to relate to the missing person anymore, according to Dr. Pauline Boss, Professor Emeritus at the Department of Family Social Science, College of Education and Human Development at the University of Minnesota.

In order to deal with ambiguous loss, according to Dr. Boss, families of the missing must discover new hope that does not focus on the missing person. The answer, or what may be the best way to cope, can be found in the concept of both-and thinking: “I both hope for my loved one’s return and am moving forward with new hopes and dreams.” “My husband is both absent and present. He is probably dead, but maybe not.” Psychologically, in their hearts and minds, the missing person is physically gone but still here. The goal becomes one of finding the resilience to live with the mystery rather than finding a solution, said Dr. Boss.

In addition to physical ambiguous loss, it is possible to suffer from psychological ambiguous loss where a person is physically present but absent psychologically due to the state of frozen grief where the preoccupation with a lost person is so strong that one is no longer available to remaining family and friends.

It was the 19th century English poet John Keats who first spoke of “negative capability”. Keats believed people were “capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact or reason”. In terms of the missing, negative capability is the ability to recognise that there is no perfect solution, that not every question has an answer and that not every problem has to be solved.

Ambiguous loss is a worldwide phenomenon witnessed in many countries that experienced war and violent conflict including Columbia, Argentina, Chile, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Nigeria where several thousands are unaccounted for, many of whom are thought to have been forcibly disappeared, usually by the state and sometimes by other participants to the conflict. In some of these countries, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has programmes to help victims’ families to cope with ambiguous loss. In most instances, families preferred group sessions and talking with others in the same situation to individual counselling.

From 2014 to 2015 the ICRC in Sri Lanka carried out a Families’ Needs Assessment (FNA) to find out the psychological and financial situation of the families of the missing and what their needs were, with a view to alleviating their suffering. The ICRC deals specifically with those affected during and after the civil war, including the families of military personnel. The missing, who are those reported by their families as having lost contact, may have been forcibly disappeared, gone missing after arrest, lost in bombing and shelling, gone abroad or be soldiers missing in battle. The ICRC cites the number of missing in Sri Lanka as 16,000, which includes 5,100 security forces personnel missing in action.

International Humanitarian Law places an obligation on states to adopt all possible measures to account for people reported missing and to provide information about them. Experience from countries recovering from conflict has shown that the issue of missing persons hinders sustainable reconciliation as it serves as a reminder of the conflict.

The assessment found that 36 percent of the respondents believed their loved ones were dead while 31 percent thought they were alive and 33 percent were uncertain. But even the people who believed their relatives were dead still hoped they may still be alive. Over two thirds wanted to know more information from the authorities while 79 percent wanted to know where the remains were and to get them back. All those who believed their loved ones were alive wanted to know where they were. The most pressing need was the need to know followed by access to economic assistance. Eighty six percent were anxious and depressed while 56 percent were in economic difficulty. While there are services focused on psychiatric care and counselling available for those with mental health problems, there isn’t adequate care for families suffering from ambiguous loss.

“We don’t tell families that they have to just accept that their loved ones are missing, that they can’t keep looking or join protests. We support and respect their right to know. Justice and accountability are also needs. What we do is help families to cope with the situation and try to minimise their suffering,” Elodie Magnier, ICRC’s Deputy Protection Coordinator told Groundviews, adding that the disruption of family links was often not a visible consequence of conflict.

After the assessment, in 2015 the ICRC embarked on an Accompaniment Programme based on three components: mental health and psychosocial support for coping with ambiguous loss and to create awareness about the needs of families among authorities and mental health practitioners; referral services to resolve legal, administrative and economic needs; and economic support to restart or expand livelihoods. The programme will continue until 2024 and is covering all districts of the country, with 10,000 individuals expected to benefit. An assessment in districts where the programme has been completed showed a huge improvement in 80 percent of the people, with a reduction in distress and an increase in functionality.

In a culture where mental illness still bears a stigma, people preferred counselling in the form of group therapy where they could talk to others experiencing the same feelings, taking comfort in the knowledge that they were not alone.

Family members of missing persons are trained as accompaniers who work directly with other families in their own communities. They are trained to assess psychosocial needs of families and provide them with emotional support through home visits and peer support group sessions that enable families to share memories with the group through poems, art and crafts and songs or by sharing the missing person’s favourite food. Accompaniers also guide families to available services to resolve administrative and economic issues caused by the absence of their relative.

“We can’t give them closure. It not easy to find answers and it could take years to get answers. We can just help them to live with the loss and encourage them to share with others how they live with it throughout the years.

“Through the group sessions, people can see their problems in a social context and realise it is not their fault. The social network is important for healing. People can create and maintain connections that continue after the programme,” said Arundathi Abeypala, ICRC’s Mental Health and Psychosocial Support Programme Manager.

She related the story of a woman in Trincomalee whose son told her he was going out but would come back to eat the food she had cooked for him. He never returned and she has never cooked at home since. But after coming to the group sessions, she made some food and brought it for the others to share.

“People must not avoid talking about the missing person and pretend he never lived. Memorialisation is important for the process of living with ambiguity; it can be telling a funny story, cooking a favourite food or making a donation at a temple or a kovil,” Ms. Abeypala pointed out.

“My son has been missing for 26 years. We didn’t talk about it with anyone outside our family until we joined this group. Before, even though we lived in the same village and saw each other often, we didn’t talk about our shared pain. We would just greet each other in passing. Now, we know each other well and talking about our missing children has relieved us all of a heavy burden we’ve carried for years,” said a mother of a missing son.

“I feel lighter and happier after talking to other women in my group whose husbands are also missing. I have also been advising other women like me, based on my experience. Our group has a close bond now and we even talk to each other over the phone between our weekly meetings,” said the wife of a missing person.