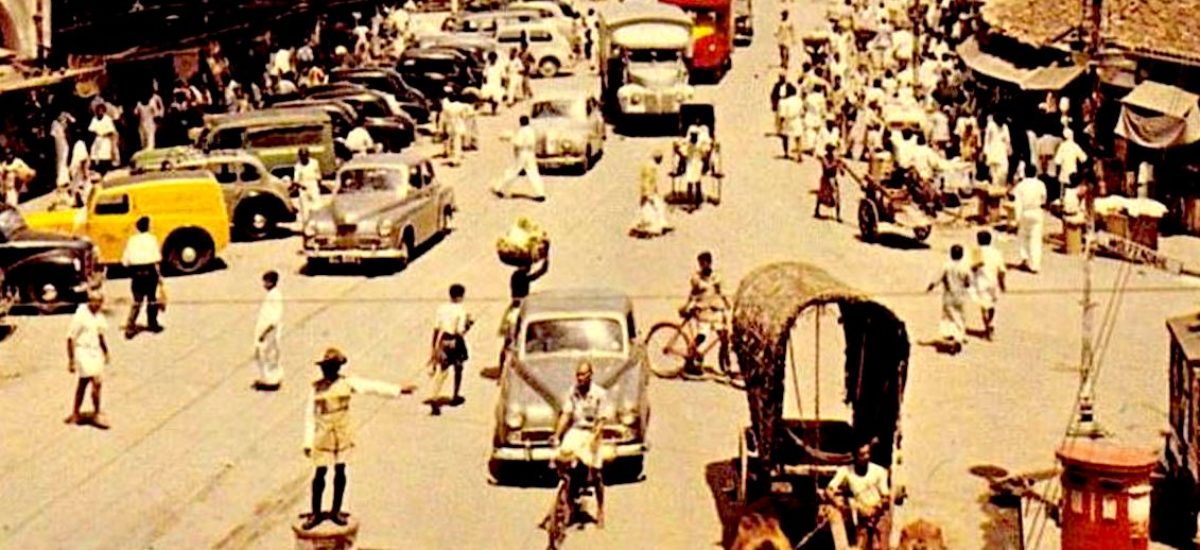

Photo courtesy of Sean Amarasinghe

“Suppose you kick out 17,000 Tamils employed by the government at the present. Suppose you tell them ‘Pack up your bags and go back to Jaffna.’ Suppose the Minister of Labor says ‘Give me 17,000 Sinhalese boys to take their place’ and he puts them in those vacant jobs. After that what is he going to do? How do you solve the problem after that?” Pieter Keuneman during the 1956 parliamentary debate on the language question.[1]

Therein lies the rub. At the heart of most of the crises that have beset the nation of Sri Lanka is a corrupt, inequitable and underdeveloped economic structure of colonial origin. Attention is diverted to various scapegoats; the system’s fundamental flaws are unacknowledged and cultural, linguistic and religious differences take centre stage. This paper does question the importance of these factors but argues forcefully that the emphasis should be on the need for serious and radical institutional and economic change to solve these pressing and festering issues.

The economic context

Capitalism came into being in Sri Lanka not as a result of a natural process of social development but as an artificial construct imposed on a feudal agricultural economy to suit the needs of its imperial overlords. Sri Lanka was a plantation economy dominated by the cultivation of tea, followed by coconut and rubber, with a very small manufacturing sector. It is an underdeveloped capitalist system beholden to foreign finance and markets for survival. When export prices were high times were good, but when

they declined it created not only economic instability but social upheaval in the form of hartals (strikes) and communal conflicts. This type of economy could not provide jobs for the burgeoning population, pay for the welfare introduced during the Second World War and fund the lifestyles of the elite. Something, therefore, had to be broken. In Sri Lanka’s case it was communal harmony.

The golden period: 1948 to the hartal of 1953

In 1949, one year after independence, the import of liquor and other spirits increased by 37 per cent, clothing by 23 per cent and petrol by 10.5 per cent. The ordinary Sri Lankan would not have the money to buy foreign alcohol or clothing or the petrol to run a car. Such things were for the elite.

Export earnings at most remained the same so that increased imports were paid for by running down the island’s reserves of foreign currency. This resulted in the government’s budgets being in deficit, and over time they had to borrow money from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

An economic snapshot of 1948 gives some idea of how backward and dependent the country was. Ninety five per cent of export earnings were derived from three plantation crops, of which tea accounted for 60 per cent. Over 40 per cent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) came from agriculture, with plantation crops accounting for more than a half, yet foodstuffs accounted for 52 per cent of imports because of the gross under utilisation of land and labour. The domestic agricultural sector used 85 per cent of the island’s arable land and employed 72 per cent of the population. This sector was characterised by low yields, small fragmented holdings, and peasants who were in perpetual debt. Dr. Lionel Bopage speaking to the author estimates that 70 per cent of the rural population were landless and worked intermittently on other people’s land.

The plantation sector had, by the time of independence, reached its limits in terms of acreage. The price for the produce of these plantations was declining. Compounding this structural problem was a parasitic urban sector that lived off the surplus produced by the plantation economy and some of whose members were ensconced in the newly elected parliament.[2]

This was inevitable when the boom caused by the Korean War collapsed in the early fifties, with a drastic drop in the external assets of the country from Rs.1,208 million in January 1952 to Rs. 685 million by July 1953. The UNP government decided to cut welfare for those who could least afford it and leave untouched the bulging pockets of their backers, the elite.

This was evidenced by the budget cuts announced in August 1953: a doubling of postal fees and the price of rail tickets; the abolition of the rice subsidy resulting in the price soaring from 25 cents a measure to 70 cents; the abolition of free midday meals for school children; an increase in the price of sugar; a cutting of the public assistance rate; and the closing of milk feeding centres.

These measures were proposed by J. R. Jayewardene, finance minister at the time and the first executive president of Sri Lanka in the seventies. The lower middle class and the workers became extremely angry about these new developments.

Faced with the general strike of 1953, the UNP government seemed to capitulate, as evidenced by the fact that the Prime Minister Dudley Senanayake (son of D.S. Senanayake, who was the first prime minister of the island), resigned on the pretext that he was sick. His uncle John Kotelawela was appointed prime minister. Then the government set in motion the state’s repressive apparatus and a number of strikers were killed by the police and army. Yet the workers stayed firm, forcing the government to back down on some issues. J.R. Jayewardene was replaced as finance minister and the ration of rice raised to two measures with the price of a measure reduced to 55 cents. However, there was no change in the economic policies and class privileges of the elite. The issues of industrial development, employment and the inequitable distribution of income were left to fester. These issues would later manifest themselves in the form of ethnic conflict.[3]

1971

During the 1960s the economy of Ceylon, as it was known then, was characterised by sinking export income, growing foreign debt and escalating unemployment.

Throughout the 1960s the share of industry in Gross National Product (GNP) remained almost constant, rising from 12 per cent to 13 per cent with the major source of income continuing to be services and agriculture.

To pick up the slack, the United Front government intervened to widen manufacturing in the form of state enterprises. Due to a lack of foreign exchange for importing raw materials, production did not expand, dooming it to failure. Many of the government factories were later sold off to J.R.’s financial backers.

The dependence on primary agricultural products was far greater for exports than production as a whole. The country suffered from the classic economic pincer move – declining export prices and rising export costs.

In a typical year of this period – 1967 – exports earned Rs, 1,690 million, with tea representing 63 per cent, rubber 17 per cent, and coconut products 10 per cent. Ninety per cent of the country’s exports came from three products.

So it came as no surprise that the country’s debt rose from Rs. 95 million in 1957 to Rs. 349 million in 1966 and to Rs. 744 million in 1969. Ceylon’s economy was still controlled by a mixture of foreign interests and a parasitic local bourgeoisie.

The surplus for investment and to finance foreign debt did not come from local capitalists, large landowners and the increasingly corrupt political elite but from foreign loans and running down Ceylon’s foreign exchange reserves.

In 1970 Lanka spent more importing chillies than it earned from tourism. It is sobering to think that in 1971 foodstuffs made up 53 per cent of her imports.

According the figures released by the Central Bank of Ceylon, the country’s foreign debt in 1955 was Rs. 205 million. By 1969 it had risen to around Rs. 1,375 million.

In the meantime, the population had increased. In 1946 the population of Ceylon was 6.6 million; by 1970 it had almost doubled to 12.5 million.

The country had impressive literacy rates – 80 per cent, second only to Japan. Every year 100,000 new school leavers entered the job market but notwithstanding the literacy rates and welfare provisions, per capita income in 1971 was a lowly $132.

Unemployment, as shown by government statistics, continued to rise. In 1971, out of a labour force of 4.4 million, 585,000 were officially unemployed. Dr. N.M. Perera, the economic tsar of the United Front government, estimated the figure to be closer to 700,000.

For two and a half decades from independence to 1971 there was no agrarian reform. Foreign loans were used to finance the import of consumer goods and the creation of costly public white elephants.

Out of the 585,000 unemployed, 460,000 were in rural areas and 250,000 were aged from 19 to 24. 167,000 of these had received a secondary or tertiary education. The structural limits of Ceylonese capitalism had been reached and something had to give but little realisation of this seemed to have occurred to the country’s elite and in the corridors of parliament.

The moral of 1971: the children of 1956 were not getting the fruits promised to them. Something had to give. It was civil liberties and civility with between 10,000 and 15,000 deaths in the JVP uprising.[4]

In tandem of the rising discontent of Sinhalese youth, young Tamils felt increasing marginalised and victimised by the Sinhala Buddhist State. The reasons are not hard to discern. Between the passing of the 1956 Official Language Bill to 1970 over 200,000 people had been recruited by the state to people their state corporations; around 99 per cent were Sinhalese. By the time of the 1983 Black July riots (more of a pogrom) only six per cent of Tamils were employed in the public sector. By 1983 Sinhalese who represented 75 per cent of the population had 85 per cent of all public service jobs, 82 per cent of all technical and professional positions and 83 per cent of all managerial and administrative appointments.

Meanwhile the standardisation of results to enter university were weighted in the favour of the majority community, further alienating and marginalising young Tamils. The declaration in the 1972 and 1978 constitutions, privileged the majority. Exacerbating their economic misery is since the late 1950s the North and the East were starved of government funds.

This deliberate marginalisation, economic discrimination and racism by the Sinhala state radicalised Tamil youth and fuelled the 30 odd year disastrous and violent civil war.[5]

2015: A new beginning?

By the 1980s the economic direction changed; neo-liberalism became the mantra. Sri Lanka was portrayed by its cheerleaders as a vibrant growing economy with a standard of living comparable to other middle level countries.

The country was now dependent on tourism, garments and remittances – not a diverse manufacturing sector. The national debt continued to increase. More money was borrowed with no thought given to how the debt would be repaid.

Add to this the fact that the vast majority of the population, given the informal nature of employment and business practices, do not pay tax and that the largest share of government revenue is devoted to the military, dwarfing expenditure on health and education.

Sri Lanka still produces few of its avidly sought consumer goods like phones and TVs. The top 20 per cent of the population enjoy 42 per cent of the island’s income while the lowest 40 per cent make do with 17.8 per cent, making them vulnerable to economic shocks.

Individual debt aside, national debt was now 79 per cent of GDP. The educational system is not producing the quality graduates the country needs (the elite educate their students abroad or in private and expensive international schools). For the students that graduate at tertiary and secondary level there are not enough jobs and university positions to meet their expectations. Very little is spent on health services. Many families are forced to rely on the expensive private health system and are reduced to penury as a result. Meanwhile the security services take an unreasonably high share of government revenue. The result is an economic and political powder keg.[6] Just before Covid, national debt went beyond 100 per cent of the country’s GNP, further restricting the country’s ability to pay.

2022

Meanwhile the political tamasha continued. Scapegoats in the form of Muslims were pursued; cronies and family members were given plum jobs; the Rajapaksa clan and its allies continued to enrich themselves. There was neither transparency nor accountability, to hold them to account for their various nefarious activities.

This house of cards was bound to collapse under the weight of its own contradictions. It was hastened with the onset of COVID, the Ukraine war and spectacularly bad economic decisions by the current regime.

Conclusion

The country sadly has been susceptible to the dog whistle of the ‘other’. Hopefully, no more. The emperor and his enablers are naked and their greed, nepotism and incompetence are there for all to see. What happens now is now up to the people of Sri Lanka. The choice is stark, more of the same or a clean slate not only in terms of intercultural harmony, transparency and the rule of law but just as importantly, the economic bedrock and the relations therein. All of which will form the basis of a good society.

[1] Keuneman, Pieter (1987). Selected Speeches and Articles (1947 – 1987). People’s Publishing House, p. 106.

[2] Ponnambalam, Satchi (1980). Dependent Capitalism in Crisis: The Sri Lankan Economy 1948 – 1980. Zed Press, pp. 11 – 15.

[3] Cooke, Michael Colin (2011). Rebellion, Repression and The Struggle for Justice in Sri Lanka: The Lionel Bopage Story. Agahas Publishers, pp. 39 to 41.

[4] Halliday, Fred. (1975) The Ceylonese Insurrection in editor Blackburn, Robin. Explosion in a Subcontinent: India, Pakistan and Ceylon. Penguin Books with New Left Review, pp.151 to 220.

[5] Op cit: Cooke, Michael Colin (2011). Rebellion, Repression and The Struggle for Justice in Sri Lanka: The Lionel Bopage Story, pp 235 to 294.

[6] See Hettige, Siri (2015), Towards a Sane Society, Sarasavi Publishers, for a fuller exposition of these matters.